Only a single word comes to mind that I humbly believe can describe Jeff Lemire’s body of work, that is: silent. Whether it’s his indie hits such The Nobody or Sweet Tooth, or the triple A titles of Old Man Logan or Animal Man, there is a deafening, desolate silence that blankets their pages. I, of course, mean this with the utmost respect, love, and fear.. And none other compliments his mastery of silence so well than Andrea Sorrentino.

Silence isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it does not solely imply a lack of dialogue on a page. If wielded correctly, silence can paint a whole world for a reader even if there is no tangible, visible background illustrated for them. Silence can be both serene and terrifying, liberating and suffocating all at once. Sweet Tooth is quietly apocalyptic, The Nobody perfectly captured the agonizing isolation of small, intimate towns. Even at its bloodiest, Lemire’s Old Man Logan had sweeping, empty fields and landscapes.

When you take the silence of Lemire’s writing and the dark, dramatic pencils of Sorrentino, blend it with season one of True Detective, you get Gideon Falls.

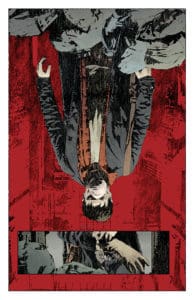

Gideon is a perfect case study of the breathability of Lemire’s storytelling. Right away, readers are introduced to two differently broken men: Norman Sinclair and Father Fred. But despite juggling two main protagonists, in different settings, there isn’t one part in its premiere issue that feels cumbersome with exposition. In its opening pages, we meet the neurotic, kleptomaniac Norman, standing over a pile of trash, in an upside down, deep red panel.

Panel and page experimentation is a reoccuring theme in Norman’s side of the story. Before the sequence where we learn the nature of Norman’s mental illness, there is an underlying, creeping sense of madness. Norman’s panels don’t take up the entire width of the page, forming meticulous shapes and leaving much of the page empty. However, the reader’s eye is drawn into tight panels of Norman collecting trash. Without the use of words, dialogue or narration, the reader is enveloped by the tedium of Norman’s obsession.

Father Fred’s pages stand in contrast to Norman, being more conventionally cinematic and containing more dialogue. Although lacking in abstraction, Fred’s pages still utilize the same trademark Lemire silence, and are more akin to Sorrentino’s work in Old Man Logan. The book introduces Father Fred through a flashback.

After what can be assumed a fall from grace, Fred is reassigned to the quaint, small farming community of Gideon Falls. When being reassigned by his Bishop, Fred sits in a bleak, empty office; a wide, deep panels conveys Fred’s alienation throughout. Even his church, in an already isolated town, is on the cusp of a desolate wheat field.

Without getting to into the details of the issue’s gruesome climax, the horror in Gideon Falls is subtle. If you were expecting something outwardly occult or violent, you’ll find Gideon Falls is really a dreamy, slow burn. Its horror lies in a subconscious downward spiral. Lemire’s ability to use silence and let his pages breathe allows Sorrentino to give as much character to his panels as Lemire to his protagonists.

To top it off, the book’s bleak and grainy colors are broken up with gorgeous, menacing reds, making the horror of Gideon Falls abstract and esoteric, all the more terrifying than a visible, monstrous threat. Fans of Fell, The Black Monday Murders, or Underwinter should undoubtedly give Gideon Falls a read.

Rating: 10/10