Dread it.

Run from it.

There’s an ugly specter looming over all of us.

No, it’s not a purple Josh Brolin with some shiny, space jewelry. It’s the deeply entrenched, complex racism and xenophobia that is at the forefront of conversation today. For some, it’s terrifyingly subtle, and egregiously overt for others. Either way, it most certainly will not disappear with a snap anytime soon.

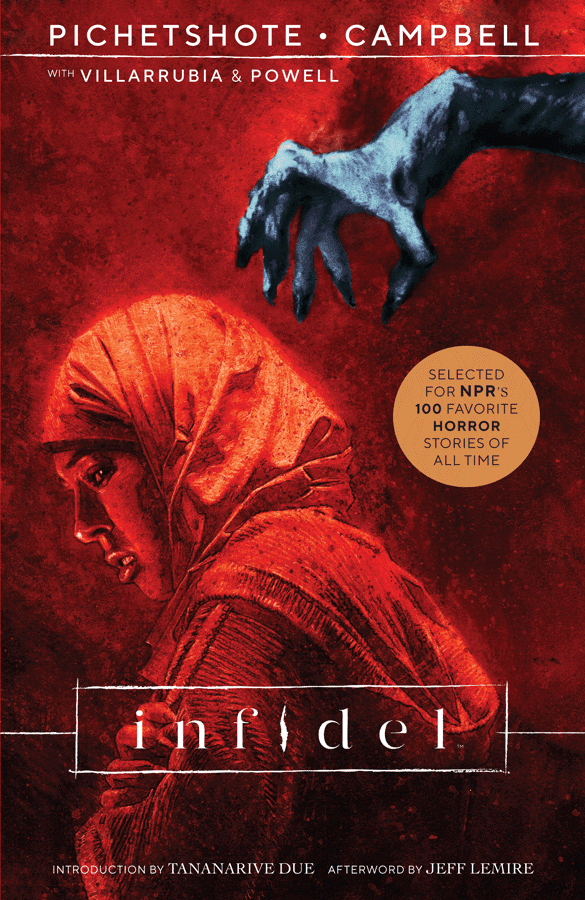

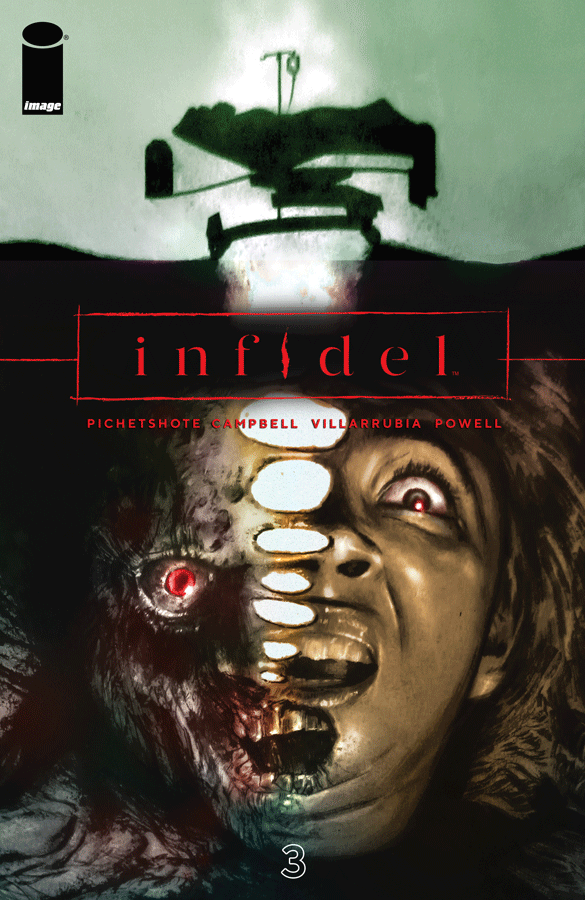

So it only makes sense that Image’s hit, summer mini-series Infidel — a modern, American ghost story in which bigotry is scarier than violent poltergeists — landed a movie deal just by its second issue.

This past San Diego Comic Con, we had the opportunity to chat with Pornsak Pichetshote and Aaron Campbell, Infidel’s writer and artist respectively on the book’s creation, conception, and its spectacular rise to fame. The entire collection of Infidel has just been released this week and should be on the bookshelf of any self-proclaimed horror fan.

Upon opening the first few pages of Infidel #1, the horrifying painting “The Nightmare” immediately comes to mind, all the while the entire setting of series feels oddly reminiscent of “Rosemary’s Baby”. Was there any specific pieces of pop culture or imagery you pulled from that you knew would resonate with your readers?

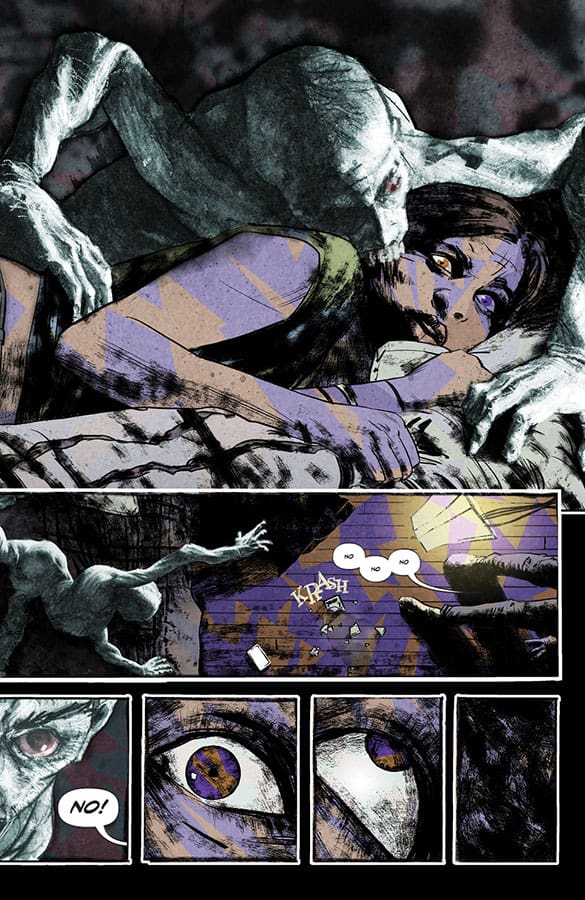

PORNSAK: Well, I think the bigger question is how much of other pre-existing horror that’s out there sort of factored in. A lot of Asian horror factored in. We’ve been saying a lot of manga horror, but specifically Junji Ito, who did Uzumaki, who did Gyo, was a very big influence on the way the body horror is presented throughout the book. So much so now, it’s going to be a tradition whenever I start a new book. I bought a copy of Uzumaki, sent it to Aaron and José [Villarrubia] to get them on the same page of horror I think works.

One of the things I did when I started doing the book, and for me is the funnest part of the comic, is you get to do the “research”. You just read old comics. For me, it was finding out what scares got me and what didn’t. And Ito got me more often than not. What he tended to do with his body horror it had a lot to do with the perversion of the body, what José would later tell me, perverting the body without breaking it.

A lot of the scary visuals is what I served up to Aaron, to let him riff from there. We come from a long tradition of haunted house stories, but I didn’t necessarily point to anything specific thing, like “make it like this,” or,”make it like that.” I will admit there are some in the script, like “here’s a shot from a horror movie” to evoke it. But usually it was a very obscure horror movie as opposed to a super, popular iconic thing.

AARON: I thought vaguely about The Thing. But going to the body horror idea and not breaking the body, that’s kinda where I went. Depicting the ghosts in their final moments of life, right in the moment before their final bit of consciousness left them in this traumatic event. The other thing, in terms of body horror in pop culture, especially in film, you end up with this overtly sexualized content. I wanted to turn that on its head and make the sexualization of the spirits be the sexualized aspect, not the main character’s, which is often the case, then take the sexualization and make it grotesque and violent. So that the nudity is no longer titillating, it’s repulsive. It reverses that whole dichotomy that has always existed in horror.

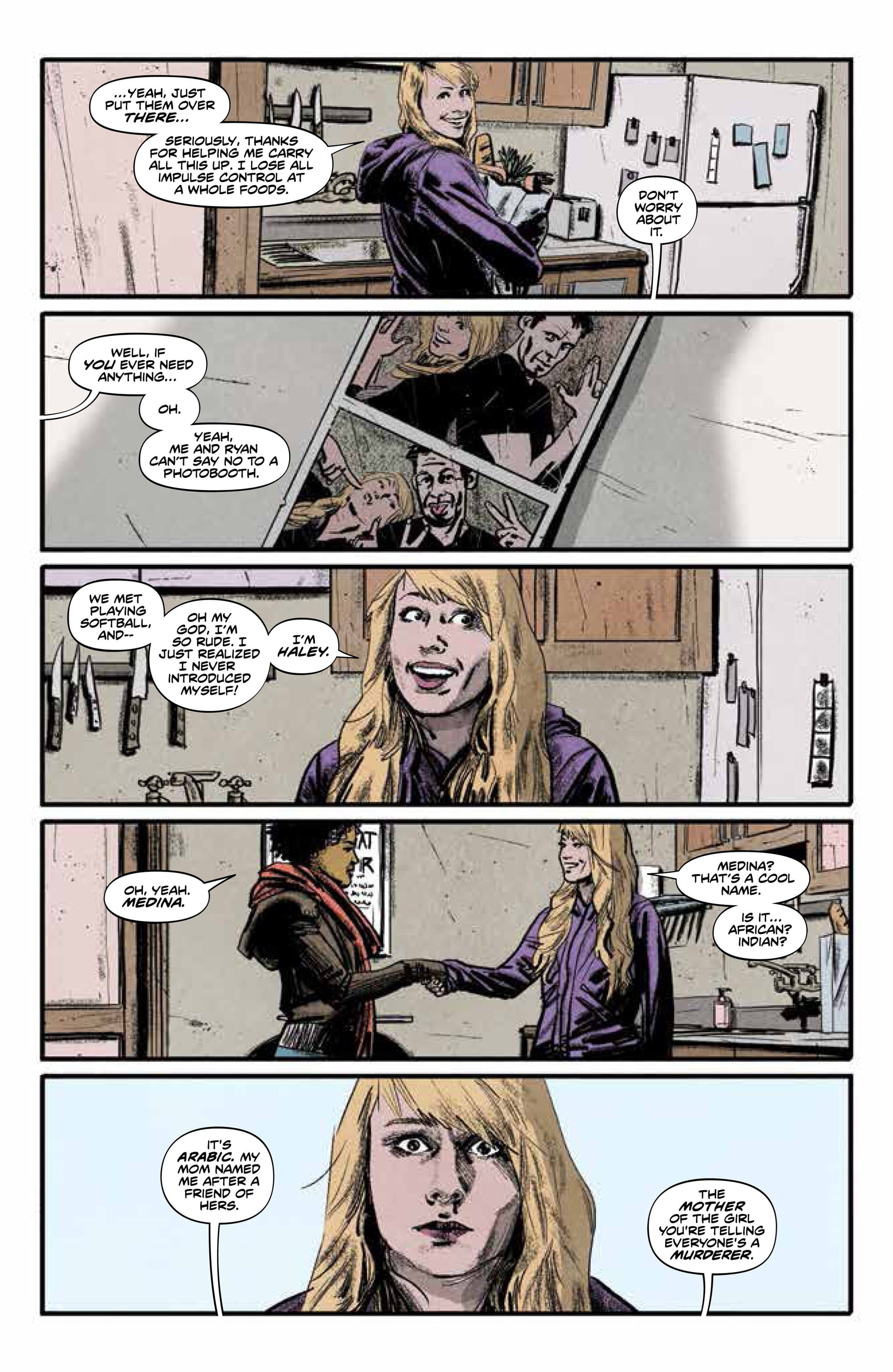

The demons of Infidel are often invisible except to a few select characters, mainly characters who are people of color. Is there an allegory to be found in the invisibility of these monsters and the xenophobia and racism that is ever more pervasive in the daily lives of real POC’s?

AARON: Racism, bigotry, and bias are often invisible to those who don’t have to suffer through it. That’s why so many can’t believe that things like police shootings could be racially motivated or influenced. For many others, they refuse to see it. They willfully deny its existence because to accept it would mean marginalizing their own perceived plight. And so, the specter of racism remains hidden from their worldview.

PORNSAK: Yeah, there was definitely a lot of thought given to the allegorical nature of the story. So much so, I wanted to be careful spelling and stepping it out too much for the reader. I think part of the fun of any reading experience is giving the audience the room to interpret these things for themselves. That said, there was a lot of thought put into who can and can’t see the ghost and its relation to bias as well a couple other facets: the people who would eventually become the ghosts; the logic behind how they appear as ghosts; the nature and practice of gaslighting; the isolation Aisha feels throughout the book even though she’s surrounded by friends and family; how the Asian-American experience factors into the equation… We liked the idea of leaving room for the reader to participate.

Mainstream horror has explored the same Western tropes to ad nauseam, but in Infidel you created a hybridization of Islamic folklore and the familiar haunted house. Pornsak, being a Thai-American yourself, are there any Thai folklore or urban myths you’d want to introduce to Western horror fans?

PORNSAK: There are a couple Thai folk tales I’ve heard of that are definitely grist for the mill, but the thing about Thai folklore that really imprinted the most on me is how when I was in Thailand for high school, I was literally the only kid I knew that didn’t have a story about the first time they interacted with a ghost. Literally everyone else I knew did. The ubiquity of spiritual visitations and how people take that for granted is something that definitely was a big influence on Infidel.

Aaron, there is some seriously memorable body horror in this series, can you explain your process in designing these monsters?

AARON: The ghosts appear as they did in the exact final moment they were still alive. As the force that killed them twisted and broke their bodies, the spark of consciousness remained for mere milliseconds. That is the image of themselves that was projected into the afterlife. It is the final expression of their rage, the thing that fuels what is left of their psyche; hate.

That hate then continues to twist and deform them. It boils and blisters to the surface reshaping them through every consumptive, fearful, angry, racist, anxious thought. Their bodies become a crucible burning away anything that was once good about them. This is what racism does. It is a thief that comes for your humanity.

The comic was only one or two issues in, then “BOOM,” movie deal. I know this is not new, look at Mark Millar. What was that day for you two when you found out?

PORNSAK: It was cool. It’s always nice to know people are digging your stuff. That was nice. There were a couple people interested, it is always nice to have a couple people fighting over what you want. It’s funny for me, and Aaron can speak to what it’s like for him personally, my nervousness, my anxieties, and my excitement are more wrapped up in how people respond to the book. In so much, it’s a response to the book that I feel excited. But at the same time, it’s the people who are reading the book. The most nervous I have been is this week, when the finale comes out. And all the things come together, whether or not we stuck the landing. The fact that reviews are coming out that they like what we’re doing, that’s a huge relief to me than it is more so than a movie deal, which is obviously nice and great financially. The movie deal is more satisfying in so it involves people interacting with the book.

AARON: For me, it was kind of mind blowing. Because I’ve been kind of huddled in my studio for eight years or nine years drawing comics, never really expected to go any further than this particular medium. As I progressed in my career, I’ve started to realize there’s an interesting opinion about film and comics. There’s purists, and then there’s the people wanted to see it adapted. For me, I started to develop this opinion over the years that the audience that reads comics is a relatively small audience, then there’s an audience for film and television, that no matter how hard you push, they will never read comics.

The idea that our story can now reach a worldwide, massive audience even if it ends up being a film, obviously adapted and changed, the core elements will be there. The idea that our story can reach a mass audience is incredibly exciting for me. But at the same time, like Pornsak, manage expectations cause it may never happen. At the core, what I think is the best, it says to us there’s real inherent value in what we have done. Because someone who is making decisions based on economic reasons has said “This is worth gambling on, the content here is valuable.” That is incredibly satisfying.

With representation and Hollywood whitewashing being at the top of our rhetoric now more than ever, do either of you have reservations about “Infidel” making its way through the film industry?

AARON: I think Hollywood is learning its lesson and with a production company like Sugar 23 and Anonymous Content handling this, I’m really not that concerned. But even still the comic will always remain what it is. That cannot be changed.

PORNSAK: 100% agree. First of all, because representation and Hollywood whitewashing are such hot topics at the moment, I feel like now is the perfect time for something like Infidel to be adapted and have the representation remain faithful in the film version of the story.

But also, the way I look at the film adaptation is different I believe than how people expect me to view it. I’m not possessive or have a huge personal investment in having any creative choices be any one specific way, primarily because my ideal version of Infidel – which in my opinion embodies all the best creative choices – already exists in the form of a comic. The film’s choices won’t ever really take that away.

Not only that, the way Infidel was written, I found myself constantly thinking, hey, let’s do the version of the scene, the scare, that movies couldn’t possibly pull off, because I think that’s how you make the best comics. As a result, I’m curious what might change in the process of turning it into a film, but the story I wanted to tell has already been told. Do I believe the best version of the story stars the ethnic breakdown I chose for the comic? Absolutely. But I’m curious if the person who adapts it agrees with me, and what might be gained or lost if it’s changed. All things I’m curious to see, and potentially learn from if their instincts were more on point than mine or be glad I stayed away from if they’re not.

Everyone wants to work for the big two, Marvel or DC is the dream. Maybe write Spider-Man, contribute to the Batman mythos. There has to be something gratifying about Image or Skybound, these creator-owned publishers where you can come in with an idea and say “I wanna do four issues and this is the idea” and have that out there. When you developed Infidel, were you thinking of Image?

PORNSAK: Image was the first choice primarily because of the freedom that they give. The thing that was different about how this book was made as opposed to how other books are made, and I think I wanna keep this difference going, my first call wasn’t to an artist. My first call was to an editor. My first call was to my friend José, who’s a colorist who I love talking about artists with. So when this book came up, it was an excuse to call my old friend. He was the one who said “Hey, I’d love to edit this.” Then we kinda built the book from there.

Once we started with that, my belief was the places we could go got limited. Most publishers have in-house editors that require you to work with. So José wouldn’t have been able to edit it perhaps, or the process would’ve been diluted or changed. Image became the best place for that reason. There was all the other pluses you get with Image. Right now, I think we’re in a really exciting time with comics. There’s talk about wanting to work for The Big Two, for me the excitement is happening outside of all that. It’s creating a new idea, how to get people excited about new ideas, and how to build ideas that make the most.

Hollywood has kind of glommed onto comics from the big publishers. This is my personal philosophy, there is such a threshold for what a book has to do now to accommodate all the multiple VPs in that company. Now to be able to make a book at a smaller scale, to be able to pair a book down to just the essentials so all the people from the book can profit from the book. We do profit sharing, everyone who’s worked on the book shares in the profits, which is not typical of Marvel and DC.

The opportunity to build new business models and with the freedom that Image gives, that’s exciting to me and that’s where the cool things you are going to see from comics come from. Unfortunately, we’re at this point where Hollywood kind of knows what the ideas of The Big Two are. There’s no Marvel or DC thing that people are like “Oh my god, we didn’t see that coming.” There’s different permutations, the Marvel movies are turning into team up movies because that’s the new way to get people excited. But the idea of making new ideas, starting new ideas, how to catch fire, that’s where I think the excitement is.

AARON: It’s more with the DC and Marvel stuff, it’s not like “Oh my god they’re making that,” it’s more like “Oh that’s cool they’re finally making that.” Where with Image, it’s “Oh they just created this. It’s gonna be this, it’s gonna be that.”

PORNSAK: Yeah, again it’s the discovery of the new, I personally love as a reader.