If I had a time machine, I’d make two stops. The first would be during the years when Warren Beatty was ayoung, beautiful and would sleep with any woman with a pulse. The other would be sometime during the late ‘70s, when Studio 54 was the Mecca of the disco scene.

Though the former is still an impossible dream, director Matt Tyrnauer’s new film, Studio 54, almost achieves the latter. Scored by some of the biggest hits of the disco era and assembled from archival footage, photographs and both old and new interviews with those who worked at the New York City nightclub, the film is just as much a tribute to the club as the two men who created it.

Those men are Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager. Tyrnauer introduces them as young, fresh out of Syracuse University and hungry to break into New York City’s club scene. After trolling through Manhattan’s various hotspots, they settled on a disco club because as a current day Schrager explains, only gay and black clubs played the genre at the time and the atmosphere at clubs like Sanctuary and Le Jardin felt secretive and “subversive.”

Their location choice was equally eccentric, an old opera house on 54th Street and 8th Avenue in Manhattan that had previously been a CBS TV studio where The $64,000 Question and Captain Kangaroo were filmed. Without a permit and in a mere six weeks, Rubell, Schrager and their team (including architect Scott Bromley and lighting designers/Broadway vets Jules Fisher and Paul Marantz) renovated the space. The opening on April 26, 1977 set off a whirlwind 33 months full of drugs, alcohol and celebrities.

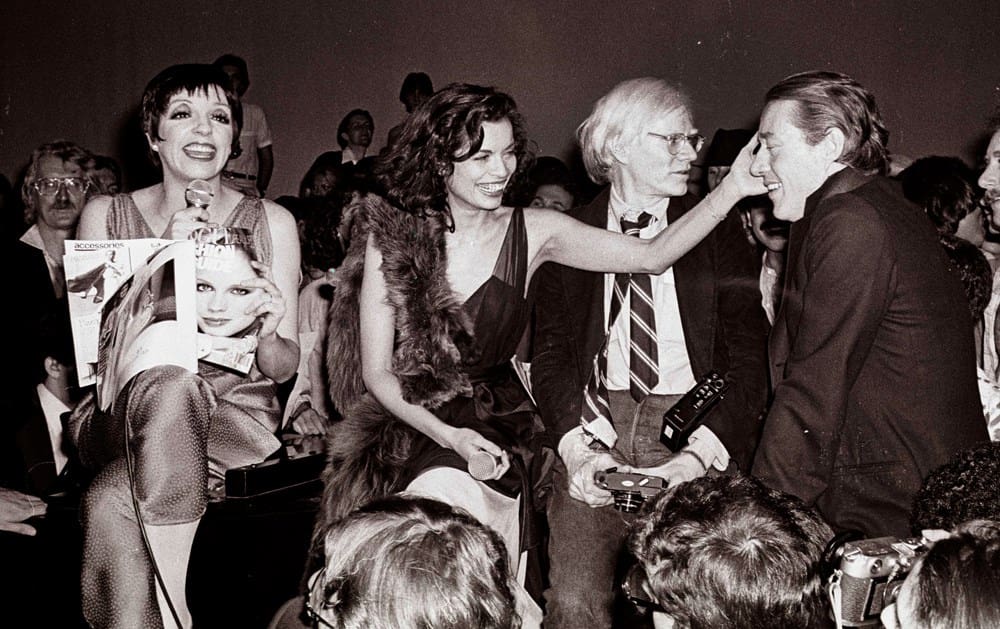

Tyrnauer covers that wild and complex history quickly and efficiently, relying largely on archival footage and pictures taken at the time by photographer Ron Galella. In them, we see one celebrity after another. We go from Truman Capote sitting on a couch to the infamous photos of Bianca Jagger riding into the club on a horse. We see Liza Minnelli chatting with Andy Warhol, Elton John feeling Divine’s boobs and even a TV interview with a young Michael Jackson, who explains that 54 is his favorite “discotheque” because “it’s where you come when you want to escape.” “You just go wild,” he adds before the movie cuts to footage of Jackson on the dance floor.

All those incredible images convey just what an incredible scene Studio 54 was, but the best moment comes when Trynauer recreates what it was like to walk into the club for the first time. From footage of Rubell and doorman Mark Benecke turning people away for wearing an ugly hat or not having a fully-shaved face, the movie cuts to the dark, mirrored entrance hall. As interviews with club-goers play, the muffled notes of Sylvester’s “Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” play low on the soundtrack. The volume rises as the camera approaches the doors, bursting to full strength as images of half-naked dancers, flashing lights and fake falling snow play on the screen. It’s one of the best musical moments in the film, but many are just as effective, and each helps the viewer imagine what it must if have felt like to be on that dance floor.

If the film’s goal were just to recreate Studio 54, it would be successful if a little shallow, but Trynauer’s real concern is Rubell and Schrager’s partnership. Where Schrager was a reserved lawyer who deliberately avoided the dance floor, Rubell wanted to be seen, often taking pictures with the club’s famous clientele and sometimes giving those same celebrities drugs like Quaaludes or cocaine.

Unfortunately, Rubell’s braggadocio drew not only the IRS’s ire (which indicted him, Schrager and their silent partner, Jack Dushey of skimming $2.5-$3 million off their profits), but president Jimmy Carter’s after Rubell alleged he’d seen Carter’s chief of staff buying cocaine in Studio 54. It’s a fascinating history and one Trynauer keeps grounded even as it gets crazier and crazier, but it’s also a downfall those expecting a movie about the hedonism of Studio 54’s heyday may not expect or enjoy.

Still, unexpected as Trynauer’s examination into the club’s downfall may be, it’s hard to deny how effectively he conveys the importance of Rubell and Schrager’s relationship. Though Rubell’s actions may have led to him and Schrager serving jail time and ratting out fellow club-owners to shorten their sentences, a current day Schrager notes that the experience only made their relationship stronger.

Sadly, we can’t know if Rubell felt the same since he died of complications due to AIDS in 1989, but it’s telling that the pair created the Palladium club in the ‘80s, owned hotels together and even bought a vacation home on Long Island. As Schrager says in an old interview, their friendship felt more like that of husband and wife rather than business partners and though that may not be as glamorous as Studio 54, it’s what made the club possible.

By the same token, Studio 54 may not be a carefree look at the most iconic and opulent artifact of the disco era, but as a current-day Schrager explains, “Studio wasn’t a nightclub, it was a kind of social experiment.” Surely the men who conducted that experiment deserve just as much recognition as their subjects.

Rating: 7.5/10