We’ve been trained to take sides in stories of divorce. Whether it’s in a movie, on a TV series, or in real life, we’re always forced to examine the end of a relationship through a lens of who did something wrong? But, sometimes, it isn’t a matter of one person doing something wrong — it can be a perfect storm of character flaws, societal pressure, and other outside forces that don’t even seem relevant but press on to all parties involved.

Paul Dano’s Wildlife is all too aware of this truth and, in capturing the end of one couple’s marriage circa 1960, reveals how complicated people can be — and how they all deserve our empathy, even when they do something that may be deemed improper.

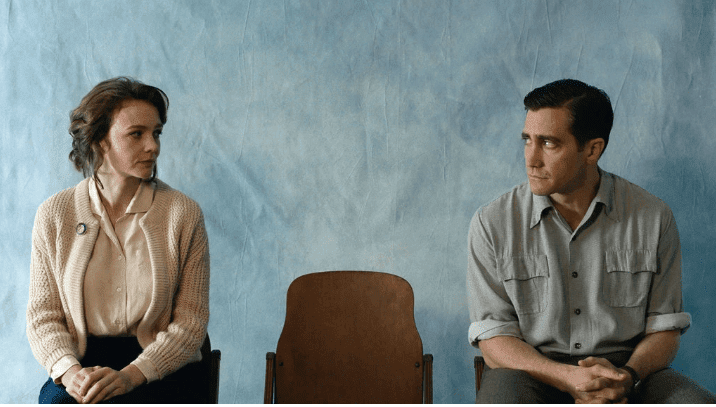

Wildlife, however, is told from a child’s point of view. Our vessel into this family is 14 year-old Joe (Ed Oxenbould), an aspiring photographer who is trying to find his place in life after moving to Oklahoma with his parents. Joe worships his father, Jerry (Jake Gyllenhaal), but their relationship takes a bizarre turn after the patriarch loses a job and, in an effort to patch up his shattered sense of pride, signs up to work as a firefighter in a mountainous region nearby, abandoning his family in the process.

This change forces Joe’s mother, Jeanette (Carey Mulligan) to think on her feet. This being the 1960s, however, the opportunities for a woman with only a high school education and no work experience are slim. So, she begins to cozy up to a rich divorcé in the town (Bill Camp), hoping that, should something happen to her husband, their financial security will stay in tact. As Joe sees new sides to his parents, the audience begins to process the different forces that are destroying this family.

The most important thing to note about this film is that it is, above all else, empathetic. Jerry and Jeanette are imperfect people, but they are never shamed for their choices. This is particularly true for Jeanette, who becomes something of a co-lead for the film, even though all of her scenes are filtered through the eyes of her son. While Dano’s direction is restrained and quiet, the film’s screenplay does some remarkable heavy-lifting in developing all three main characters.

Based on a novel by Richard Ford, and co-written by Zoe Kazan (Dano’s partner in both screenwriting and life) this script is remarkable in how it uses every word and nonverbal decision to further flesh out its characters. Without ever explicitly revealing how gender and class play into the end of this marriage, audiences are able to understand just how hard it is to make a marriage work and, furthermore, makes it possible to care about both parents even as they break their child’s heart. This strength is undoubtedly because of Dano and Kazan’s decision to write together, offering both a male and female perspective to the proceedings. It’s a level of insight that does wonders for the movie—especially when it focuses on Jeanette.

As played by Carey Mulligan, the Brinson family matriarch is a complicated figure who is constantly swapping personas as a method of survival. She’s a doting wife and caring mother and, later, plays the role of seductress and damsel in need of rescuing in order to woo a new man. Even as Joe becomes frustrated with his mother and hurt that she’d give up on her marriage, the script never lets you feel anything but sympathy for her. No matter what role the character is playing at the time or how sincere that character is, the common thread is a genuine love for her son, and a relatable sense of disillusion for the life she thought she was going go live.

Mulligan completely shines in the part, giving the audience insight into what mask her character is currently wearing and, whenever necessary, shedding her emotional costume to reveal the character’s true thoughts. In one brilliantly staged scene, where Jeanette brings her son to the home of her new beau for dinner, Mulligan quietly delivers the most devastating line of the year, piercing the heart of the viewer with her emotive eyes before replacing her facade and brilliantly playing the part of a woman pretending to be drunk to charm a man. It is masterful, complicated work, and a part that finally lives up to Mulligan’s considerable talents.

It’s rare to see a film explore a topic as sensitive as divorce while still striving for a sense of fairness and desperately trying to present all sides of the marital dissolution fairly — especially when told from a child’s point of view. While about as far away tonally as one could get, the film is reminiscent of last year’s brilliant Lady Bird in the way it understands that both children and parents are flawed, and that becoming aware of those flaws is both an important rite of passage and the key to building healthy relationships.

While much of Wildlife is deeply unpleasant and, most likely, quite triggering for children of divorce, its final moments are a thing of bittersweet beauty: we see that relationships are very rarely perfect, but that a real love worth celebrating is rooted in empathy and unconditional love in the face of character flaws. This is one of the most remarkable films of the year, and one that will, hopefully, repaint the way audiences interpret stories of divorce.

Rating: 10/10

Comments are closed.