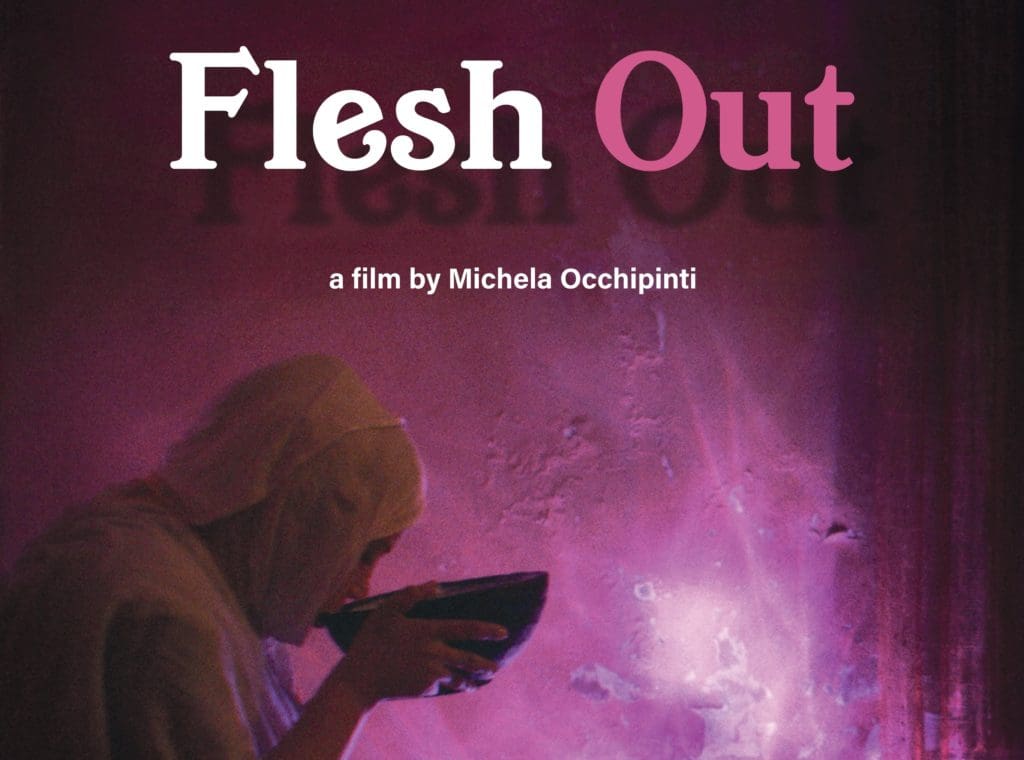

What does it mean for a woman to be beautiful? In contemporary Western culture, it typically means being skinny. However, in Mauritania, a country on the northwestern coast of Africa just north of Senegal, big is beautiful. There, women practice gavage, the act of force-feeding. It is especially prevalent among women engaged to be married, who try to gain weight in order to make themselves more attractive both socially and physically to their future husbands and their families. Director Michela Occhipinti’s first feature, Flesh Out, which premiered at Tribeca this afternoon, follows one such girl.

She’s played by Verida Beitta Ahmed Deiche and likely because Occhipinti and co-writer Simone Coppini drew inspiration from her real life experiences, the character is also named Verida, which means “unique.” When we first meet her, Verida has never met the man she’s meant to marry. Her mother simply informs her that she and Verida’s father have arranged for the marriage in three months and sets a meal down for her to eat. That meal, which she must consume 10 times a day until the wedding, consists of a bowl of milk and a bowl of grain, vegetables and usually, meat. In that first instance and throughout, that meal feels like a threat. Verida is never asked about whether she wants to marry or–once she sneaks a peek at her future husband and overhears him calling her ugly to his mother–whether she’d rather marry someone else, but the more we see the food, the more it feels like the embodiment of her loss of bodily autonomy.

The way Occhipinti conveys that loss of control is a big part of what makes Flesh Out so effective. She turns up the sound when Verida eats, turning it into some grotesque form of ASMR. Every slow, deliberate gulp of milk is painstaking and the close-ups of Verida’s hands scooping the food force us to imagine the way Verida no longer tastes this meal and likely begins to hate it the more she’s forced to eat it. It’s also telling that Verida remains silent and passive for the film’s beginning, simply allowing herself to be woken up at all hours of the day and obediently consuming what her mother presents. Especially after the scene where the future husband and his mother talk about Verida in such a detached way–like property–it’s hard not to think of Verida as akin to some fattened calf being prepared for slaughter and as Verida contemplates the meat she’ll eventually be forced to eat in the butcher shop, it becomes clear she begins to think of herself in the same way too.

In that instance and throughout, Verida’s alienation from her own body is a large part of what makes Occhipinti’s film so compelling. Though Verida grew up in Mauritania, she and her friends are constantly steeped in western culture and the tension between its standards of beauty and the traditions to which she’s bound is at the heart of the film’s point. Verida is meant to inherit her grandmother’s beauty parlor despite not seeming particularly interested in the job and it’s telling that the shop’s sign has a cartoon of henna being painted on a hand on one side and a knock-off image of Marilyn Monroe on the other.

However, while Occhipinti presents both standards of beauty, she doesn’t suggest any one is superior, instead portraying them as equally harmful. Though she largely does this through Verida’s struggles to stick to her gavage and her dissatisfaction with her body as she gains weight, one of the film’s most chilling scenes involves her friend Amal, played by Amal Saad Bouh Oumar. Despite being a funny, smart, perfectly lovely girl, Amal still uses skin whiteners and in an extended close-up, we watch her rub the cream on her face, the slow deliberate circles and beautiful lighting emphasizing the perverse fetishism of the ritual. While that instance is less extreme than what Verida goes through, the point is the same: regardless of the beauty standard they’re trying to achieve, what women are expected to do to meet them is often damaging and their struggle to control their bodies ultimately makes them hate those bodies.

Given that pressure, it’s no wonder when Verida eventually begins to rebel against her mother’s expectations and while that would solve everything in many movies, things only get worse here. Verida rapidly progresses from flushing meals down the toilet and fighting with her mother to taking weight-gain pills that endanger her life and dissociating from her friends. By the time her mother brings her to a force-feeding camp in the desert where girls are forced to eat to the point of vomiting only to be forced to eat both that vomit and the food, you begin to wish for Verida to find some way to escape—even if that means death.

From the opening shot, when Verida looks directly into camera over the bowl of milk she’s drinking, Flesh Out is confrontational. Like its characters, it leaves us questioning what it means to be beautiful and even more importantly, whether standards of female beauty–regardless of culture–are really anything but a way to control women’s bodies. Occhipinti’s film may not be the most fun film at this year’s festival, but it’s one of its most though-provoking and certainly one of its best.