After the initial introduction of Wayne Williams on the bridge, the customary escalating piano melody over the opening credit sequence was replaced with a haunting (children’s?) choral rendition. It was a simple enough alteration, but one that will play in my nightmares for weeks to come.

Even without extensive knowledge on the real Atlanta history of the era, Wayne Williams was guilty from the second we met him. The countless hours spent with serial killers in previous episodes have trained us to recognize in him the characteristics that unite other violent sociopaths. He is calm and confident, but also utterly matter of fact, whether recounting the events of his day or commenting on murdered children. And of course, he fits Ford’s ironclad, albeit sparse, profile. Holden is convinced Williams is his man in an instant, and we are conditioned to agree with him.

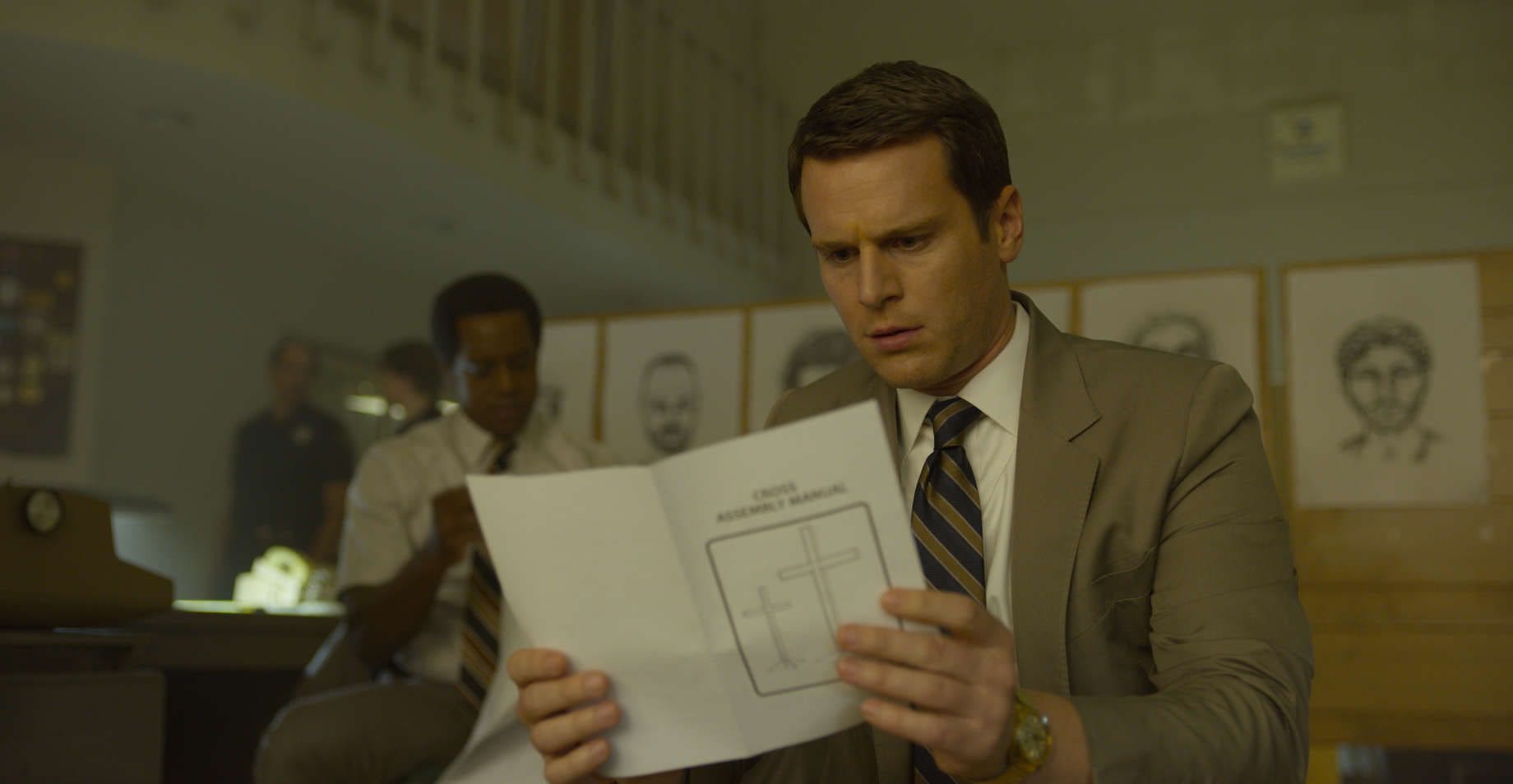

Within the first half hour of the 73 minute Mindhunter Season 2 Finale, I began thinking it couldn’t have been Williams, only because he is too bad a liar to have not gotten caught for so long. Not until the intense interrogation room grilling did I realize this is what makes him such a formidable adversary for Bill and Holden. Williams has a mountain of circumstantial evidence that makes him look more than a little suspicious, and he’s not even very good at hiding it. But he knows exactly what they have and what they don’t (thanks in no small part to the relentless reporting by the Atlanta media). He knows that he cannot prove a single one of his phony alibis as much as Tench and Ford cannot tie him to a single crime scene.

Williams weaponizes this knowledge and taunts the agents with it. Not only that, but he seizes on the opportunity the gaggle of journalists watching his every move presents and turns it to the FBI’s disadvantage. His openness and victim posturing makes the media and the public not want him to be guilty, and turns the work and investigation against the FBI and police. Williams represents an existential threat not to the legitimacy of the criminal profiling Ford, Tench and Ted Gunn are normalizing, but to the possibility of practically applying it in active serial killing cases.

Christopher Livingston turns in a great performance as Williams, and emerges as the singular star of the episode. His likeness continues Mindhunter’s track record of actors with uncanny resemblances to real life serial killers (major shout out to casting directors Laray Mayfield and Julie Schubert).

The finale also masterfully ties together and underlines the core themes of the second season in its three biggest subplots: Atlanta, BTK and the Tench family. At the center of all three is a stomach-turning sense of unknowability. But they are also connected by the tangible and real-world consequences of our fascination with serial killers.

Despite the certainty with which Wayne Williams was regarded in real life and by the show as the Atlanta Chid Killer, he was only convicted of killing two adults. The mothers of the slaughtered children were never given closure or assurance that the man who killed their sons was apprehended. But their city became a media circus and their pain became a sideshow for a nation to pretend to care about as it was all too eager to get wrapped up in a new mystery. And when Williams was arrested and charged, the mystery was over, the circus moved on and all that national interest and sympathy evaporated, leaving the mothers more hopeless for closure than ever.

Additionally, the minute glimpses into the BTK strangler’s life are becoming progressively more disturbing and offer almost no answers or details. But the notoriety and infamy of killers like Berkowitz and Zodiac give him grisly standards to aspire to and more anguish for his victims. The vignette at the end of the episode placed an almost tongue-in-cheek bookend on the cold open from the premiere. Where he was at first ashamedly auto-erotically asphyxiating himself in his home, horrifying his wife, he now does so alone in a run down motel room, having apparently lost any tethers he may have had to his less-murderous side.

The gut punch of the finale came in the form of Bill and Nancy Tench. After finally finishing in Atlanta, Bill comes home to an empty house. Tired of having the same fight and talking to a wall about her husband’s absence in their child’s time of need, and of not being listened to when she talks about wanting to move, Nancy moved herself and Brian out of their house, leaving behind only Bill’s clothes and the couch she saw no point in keeping. Holt McCallany truly grew into the center and conscience of the show this year, but Bill cannot hide that he has become more fascinated by behavioral science’s deranged subjects than appalled by them. And more to the point, more fascinated and attentive with his work than with his crumbling family. Every time he left for Atlanta, the family he came back to would be a little more broken, until one of them could not take it anymore.

Mindhunter weaves these stories and themes together with a flourish. Watching Jonathan Groff repeatedly argue to a cadre of black women that they are looking for a black killer unfortunately never lost its awkwardness, optically, but director Carl Franklin steers the story to support those primary themes as deftly as he can. Nothing ever feels like an end on Mindhunter because it has no central plot tying its characters together. But this season deliberately offers no closure on any of its main stories and leaves its audience with an effective sense of melancholy.

Mindhunter remains one of Netflix’s greatest accomplishments thanks to its incredible dialogue scenes and cast giving life to a fascinatingly taboo procedural. I just hope we don’t have to wait another two years for Season Three.

Comments are closed.