“Someday this pain may be gone / But for now, I chase the dawn / And I can feel you buried in my bones / And I’m afraid but not alone / ‘Til the light guides me home,” William DuVall sings with the utmost sense of soul-searching, retrospective honesty over a bone-chilling portrait of unplugged delicacy.

As we near the end of this decade, William DuVall is truly standing stronger than ever, as he recently released his debut solo LP One Alone on October 4. The story behind this album captures the ethereal importance of trusting in momentum when the opportunity presents itself, and how one musician with one guitar could channel the euphoric echo of those six strings into a career-defining display of gorgeous acoustic songwriting.

William DuVall’s journey to this point is one of the most inspiring stories that one could possibly ever come across in music. Back in the early ‘80s, he was a crucial influence in bringing the first wave of hardcore into Atlanta with his band Neon Christ, and this took place in one of the most conservative and segregated regions in the United States. Throughout the ‘90s, his musical pursuits expanded into a multitude of genres, including art-rock, neo jazz with No Walls, and guitar-driven, melodic rock with Comes With The Fall, which led to him crossing paths and performing with Jerry Cantrell in the early 2000s.

Ever since 2006, William DuVall has fronted Alice In Chains, one of Seattle’s most sacred bands that defined the city’s cultural revolution worldwide in the ‘90s. From the moment he stepped into this group, his impact has been tremendously felt through his soulfully cathartic and immense vocal range, and a trailblazing sense of melodic intensity and intuition to bleed his heart out into the songwriting.

Over the past decade, this band has released three of their most critically-acclaimed studio albums to-date (Most recently, 2018’s Rainier Fog) and the shear notion of this accomplishment alone, to consistently reach this unprecedented level of artistic excellence in the present, truly defies every possible odd in the book. Most inspiring of all, William DuVall has helped his bandmates overcome one of the most heartbreaking tragedies in music and together, they have resurrected their legacy and have continued to maximize their musical destiny.

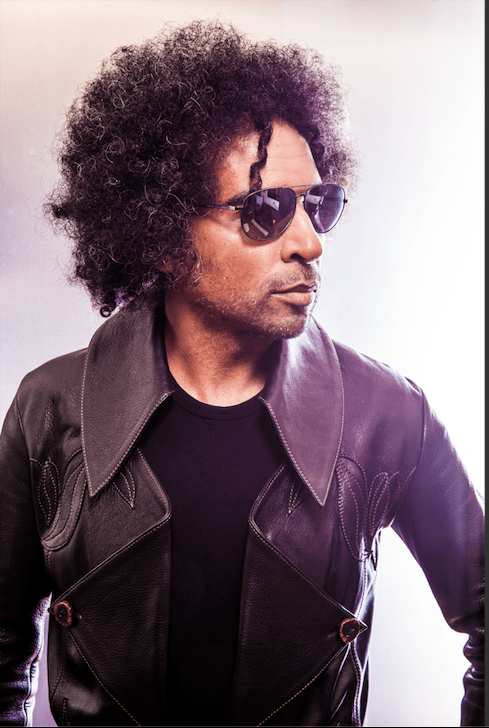

In fact, I recently spoke with William DuVall about the journey that has led him towards this milestone moment in his career with the release of One Alone. I’ve interviewed many artists over the years, and one will rarely ever come across someone so intensely committed to his craft, yet so sincere with such a calm and cool demeanor. Take the time to read through this conversation and absorb the endless wisdom that William DuVall conveys in every single answer. If you truly want to understand the sacrifices and mental fortitude that it took for William DuVall to reach this level as a performer, those answers lay within this story.

You and the band (Alice In Chains) just posted about seeing Elton John last night, which is really cool. First off, how was the show? Could you talk about the inspiration that you felt from Elton’s performance, and that post-concert emotional high so-to-speak?

William DuVall: He’s so great and he’s the consummate musician. Apart from being a legend, those two things don’t always necessarily coincide, especially when you get this far into your career. He is firing on all cylinders and the band are in top form. Some of those guys have performed together for 50 years and it’s just great to see someone who has been doing this at such a high level for so long, he is still performing at that level as though he is trying to prove something to himself. I definitely relate to that. I find it really inspirational to be around someone who exemplifies that type of drive at this stage.

Going off that point, when you guys worked with him on “Black Gives Way To Blue,” it has always stood out to me how you guys asked him to record a lot of takes. He was humble enough to listen to those suggestions and try out a variety of piano interludes. What kind of wisdom did that instill in you watching someone of his caliber be so open to all those suggestions from the band?

William DuVall: Yeah, I think it goes to show how he ultimately exists to serve the music, whether it’s his own music or someone else’s music. That should always be one’s prime directive in whatever situation you find yourself in. He’s there to do what is right for the song and what is right for the session. That is what true professionals do. It was fantastic and he came into the studio and he was all business. As you mentioned, he was very open to trying a variety of different approaches and he was wonderfully accommodating about taking direction and suggestions. He was so fantastic, and it was cool to see that from such a legend.

Talking about that professional demeanor and delving into your artistic intuition, could you talk about how you’ve always been open to different styles of songwriting, as shown by your discography? What does versatility mean to you as a musician and performer?

William DuVall: I was lucky enough to be exposed to a variety of music when I was really young. My entry into music and my motivation to stay in music has always been about covering a lot of ground; stylistically and just realizing that there are a variety of ways to tell the truth. Whatever characteristics the sound takes on, whether it’s Bad Brains, Prince, or Hendrix; you have the same objective there when you boil it all down, those people are trying to get to their truth.

The more I stayed in music and absorbed all these different sounds, the more I saw how it all related together. So basically, that’s always been one of the hallmarks of my career and one of the hallmarks of my pursuit of music from the beginning. It’s not necessarily being conscious about it all of the time but that’s just what winds up happening. That’s what has to happen to me as far as I’m concerned, that’s just how I’m made.

Going back to the beginning, you started off as a guitarist. How did the guitar initially resonate with you and when you transitioned to being a vocalist, how did your mindset on the fretboard help you find your voice and emotive delivery? Like the compatibility in your vibrato on the guitar and in your vocal approach, what ultimately led to the other and combined your approach into one?

William DuVall: That’s an interesting question. I guess I always thought like a singer even when I was just pursuing the guitar. I was always concerned with having a vocal quality to my playing, and also having a strong rhythmic sense to my playing. I was always thinking like a singer and drummer even when I was a small kid, 9 or 10-years-old playing the guitar. Again, I think that was a function of the music that I was introduced to early on.

A player like Hendrix had those qualities and whenever he played, a lot of his phrases sounded like he was talking to you and singing to you through the guitar. It was almost like you could hear words coming out of the fretboard. At the same time, he was a wonderful rhythm guitarist and one of the best ever. For a guy like that, the music all becomes one thing. It’s not like, “Oh, I’m playing rhythm guitar now. Oh, I’m playing lead guitar now. Oh, I’m now trying to play melodically.” It’s not that self-conscious and when it is, I find that it is not fulfilling for me to listen to.

For a guy like Hendrix, it was all one thing and he just was (Laughs). The guitar was an extension of him; it was all coming at you, so having that as one of my very first lessons was such a fortunate thing for me. Later on, when I saw other people trying to approach the guitar in this much more heavy, intellectual way, I did not relate to it and I still don’t.

When I was first pushed into being a singer, the music pushed me into that direction and into having me become that. I’m naturally going to bring the same awareness or approach to vocals as I did with the guitar. It was like, “Now, I’m just adding this extra ingredient and this other instrument to the mix that also comes from me.”

There’s no way that I could change my approach or be anything other than what I grew up being, you know? I’ve maintained the same approach that I had at that time with whatever else that I’m doing, and with whatever instrument that I’m going to work on. Even if it’s another instrument or something that I’m not good at, let’s say I’m playing a piano part during a session of mine, it’s the same approach. I think that’s so important; you are the music. You’re not playing the music; you are the music. And if you’re not then something is not quite right.

Focusing on the influence that Hendrix had on your playing, in the early ’90s, you worked with Vernon Reid (Living Colour) and recorded with No Walls at Electric Lady Studios. Being the Hendrix fan that you are and the age you were at the time, could you talk about the surrealness of that moment?

William DuVall: It was huge. When Vernon mentioned that we were actually recording in New York, we went to his apartment and that’s where we were hanging out. Being in New York, it got even more significant to me. I remember there was a little entryway when you walked into Studio C and came up those stairs. There was this double doorway and in-between the two doorways, there was this giant window and all of this light was shining through.

I remember when Vernon took this picture of me in there. I was getting ready to walk in and he had already walked through the door. He was like, “Hold up, stay right there.” He’s a really great photographer as well as everything else he does, and it’s one of my favorite pictures that has ever been taken of me. It really captures that moment very well because I was over the moon to be there, and the whole band was too. It was like, “Oh my god, this is all bringing it home.” I was 22 years old at the time and yeah, it really was great.

A common theme throughout your career, you’ve always played in bands with incredible rhythm sections. Playing with Hank Schroy and Matthew Cowley in No Walls, those guys ripped. How crucial was it to your progress as a vocalist and frontman to perform with jazz musicians of their caliber?

William DuVall: They were the perfect thing at the perfect time. That was exactly what I wanted and what I needed. It’s what I sought out for and what I wound up getting. That was one of those times where the universe really came through. Living in Atlanta in the late ‘80s, it wasn’t like what living in New York would’ve been like at that time where there were jazz musicians on every corner practically, almost everybody was moving to New York to go to school or moving there to get involved in the club scene.

Atlanta wasn’t like that at the time, especially when it came to more free jazz and that type of style. There wasn’t a lot of young musicians who were pursuing that type of sound. I can’t say there was absolutely nothing like that there, but it wasn’t plentiful at all and you just couldn’t expect to find those types of musicians. It wasn’t like, “Hey, here’s a dozen musicians to choose from and let me just pick one.” It wasn’t like that at all.

To come across those guys, it was like a needle in a haystack type of thing. They were both right there at Georgia Tech. I couldn’t believe my luck and our jams were something else. I still say, that was some of the best playing that I’ve ever done in my life when I was playing with those guys. A lot of the great stuff that we did, it was just between us. It was through jams that we did and we might record them on a cassette. Luckily, we used to record a lot of our rehearsals but that’s not stuff that would be on any record, YouTube, or anything like that. We did that for ourselves in our little band rehearsal room on the Georgia Tech campus.

Again, that was some of the best playing that I’ve ever done till this day. We were all seeking and ultimately, we were all trying to elevate ourselves to a higher level of consciousness through our playing. We loved music that did that like Coltrane, so we played like that. When you’re a young guy like that at 21 or 22-years-old, the sky isn’t even the limit on your energy and openness to be a vessel for that kind of playing. We were like rockets in outer space (Laughs). It really was fantastic.

Besides the notion of timing and being at the right place at the right time, could you delve into your internal perspective and trusting your gut instincts, and how that ultimately helped you pursue your path as an artist?

William DuVall: Well, I think it’s just a relentless drive for something that I’m not even sure I could put a name on. I mean, I think I used the word “truth” earlier, but I don’t even know if it’s that clear (Laughs). There’s just so many different sounds that you could make and there’s so many different pathways that you could take to pursue a life in music. For me, it was always a relentless drive to get to where I was trying to go. There has always seemed to have been a lot of challenges because a lot of the music that I love is not at all commercial, or whatever people would say.

When you’re trying to get your feet off the ground, there’s the pursuit of music and then there’s the pursuit of music as a career, and again, those things are often not compatible (Laughs). There’s a lot of challenges that you have to overcome and there’s a lot of questioning and suffering that goes along with that kind of life. I guess one of my characteristics is that I have been sort of crazy enough to roll the dice and let it ride. It’s like, “Alright, I’m jumping off the cliff and here we go (Laughs).” You must be that way. There’s no other way that you’re going to get to where I’m trying to get unless you do that, and I don’t even know if I’m going to get there. You know what I mean?

That’s really interesting because getting to this point where we’re discussing One Alone, I imagine this record has been brimming inside for a longtime. Some of the songs were originally recorded with Comes With The Fall but a majority of these songs are new compositions, so right now and in this moment, what inspired the drive to document One Alone in 2019?

William DuVall: I have always put out various music with my bands and I’ve always been a band guy. I have always believed in the band as a family unit or as a gang, and the band could be so many things. At the same time, it’s such a fragile entity but it has been such a fixture in my life for 35 years. Bands: here’s a new band, who’s in the band, who’s leading the band, and the band, the band, the band (Laughs). As we’ve mentioned, I’ve been so fortunate to perform with some of the greatest people and musicians who have ever lived, whether they were famous or not.

At some point, it was like, “Okay, I’ve got to take stock (Laughs).” I’ve had all this music for all of these years with all of these bands, and all of these different sounds, and now here we are in 2019, it just felt like a good time to be very, very productive and whittle it down. It was like, “Okay, I’ve had all these experiences and what would it sound like if I made a record that’s just one voice and one guitar?” And that’s the One Alone album.

I’ve described it before like a “cleansing fire,” where you have to burn the soil in order to renew itself and let it grow. It’s kind of like that. And while I hope this album documents where I am right now, I hope it will serve as a jumping point for anything that I might do in the future, whether it’s under my own name or under a band name or whatever. This will always be a touchstone like, “Okay, if we want to take it all the way down, this is the album where it takes it all the way down.” And we could always come back to it.

Having “Til’ The Light Guides Me Home” as the opening track hits that point home. From a listener’s standpoint, it feels like you’re in the zone creatively, especially with the melody and chord structure when you sing, “Someday this pain may be gone, but for now I chase the dawn. But I could feel you buried in my bones.” When you were working on the chorus and coming up with that finger picking pattern, what kind of vibes were you channeling as that song came together?

William DuVall: Oh god, I don’t even know because it sort of just happened (Laughs). There were things going on in my personal life that definitely triggered that tune. It all came out in one sitting. One interesting thing about the writing of that song, I had originally considered giving that song away for somebody else to sing. Part of the reason why, perhaps, it got into some really raw stuff that was going on with me at the time. It was a way of detaching myself to deal with it, and I wrote this song that in my mind, at the time, it was meant for someone else to sing.

I had originally envisioned myself giving it to a country or bluegrass artist, so when I sat down to write it, I was thinking about three-part Appalachian harmonies with banjos and fiddles (Laughs). Obviously, I was sitting there with a guitar, so I wrote the song on my guitar. And when I went into the studio to record it, the version you hear on the album was the demo that I was going to use to give to those other artists. I wonder if they were thinking, “Let me knock this out quick, so I could walk out of here with it (Laughs).”

Once I finished recording it, it only took a few minutes or whatever (Laughs), and my engineer was like, “I don’t know, man. You might want to rethink giving this song away (Laughs).” And I was like, “I don’t know, maybe?” So I was like, “Well, while I’m here, let me record these other songs.” I recorded a few more things, like you said, some of those Comes With The Fall songs acoustically, stuff that I thought would sit well and might be fun to do. I walked out with eight songs at the end of that day, so that became the genesis of the One Alone album.

So yeah, I mean, it wasn’t like when I sat down and came up with this line, “Oh man, this is great or whatever. I’m thinking this or I’m thinking that right there.” It was more like; stuff just fell out and I think it’s where my mind was at the time. Things were coming to an end, some doors were closing and there were other doors that needed to be opened, and there we were. I was just dealing with it and with all the disappointment and stuff that you feel towards yourself when you fail a situation, yourself, or whoever.

It wasn’t like I was trying to come up with some type of statement in my own mind at the time. And I think if it had been that way, it wouldn’t have happened. You know what I mean? You can’t fail and be like, “I’m now going to write the greatest song (Laughs).” You can’t do that; you killed the process before it even started. What it is, you’re always trying to get out of your own way and roll the dice. Whatever happens, happens.

I had a lucky moment where I was able to do that for a second by detaching myself and thinking about somebody else; I pictured this whole other band with a different sound playing it and I pictured this whole other record. By doing that, I was able to get out of my own way and once I recorded what I thought was a demo, it turned out to be like, “Whoa! Hey, wait a second? Okay!” Low and behold, it was the genesis for my first solo album, but I would never have thought that if I had sat down and tried to write it that way. If I had, it just wouldn’t have come out.

This album came together because you captured true momentum, 8 songs during the first session and the remaining tracks during the second session. Bouncing off your last point, could you take me through your decision to trust in the momentum and how it was pivotal in creating this record – the rawness of your approach, the live essence of these songs, the way your voice was feeling, and ultimately, the focus you had during those two sessions?

William DuVall: Whenever I go in to make my own records or any record that I’m producing, there’s just never a lot of time. It’s not like, “Well, we have this whole month. Let’s do what we want. We could play some pinball and order some takeout. We could lounge around and shoot the breeze. When we feel like recording, we could just press record. Hey, maybe we could even go deep sea fishing and come back!” It has never been that way (Laughs).

It’s always more like, “Okay, you’ve got 5 minutes to knock this out. And oh yeah, we need the final mix today too.” And it’s also been like, “Deadline. Deadline. Deadline. Deadline. Deadline. This had to be done yesterday.” All of the Comes With The Fall records were made on the strand of a shoe string. Of course, it was going to be the same for any acoustic album that I do (Laughs).

If anything, this was one of the more leisurely sessions that I have ever had because I didn’t think that I would be writing a record. The first song went down so quickly, I thought, “Well, I’m here, so let’s try out a few more songs.” It turned out to be 8 songs and it wasn’t like I set out to record 8 songs that day. When I listened to those 8 songs for a little while, I thought to myself, “Oh, this could be something. Maybe I should think about doing a record like this?” When I finally settled on that, I went in there and recorded a few more.

I feel like you either have it or you don’t. If you don’t have it or you can’t quickly chip away at the blockades, or whatever it is that is blocking you from getting there, then maybe you don’t belong in there. You know what I mean? You are kind of wasting time, money, and resources. Maybe you should break it up and get out of there. I could dig the idea of going into the studio and experimenting because I definitely understand how that process has produced some great records; the idea of going in there and you’re not exactly sure what’s going to happen. However, there has to be the pursuit of something. That’s the point and there can’t be this feeling of, “Oh, we’re just lounging around and everybody is doing their recreational activities and we’re just killing time (Laughs).”

No, the studio to me is a place where you go in there and deal with it. Working at a certain pace has always been how I roll because I’ve had too. Alice In Chains records, by far, are the lengthiest recording processes that I’ve ever been exposed too. That’s a whole other trip (Laughs) because we’re dealing with a whole other kind of thing there. With my records, it’s much more about cutting it to the chase (Laughs).

Lyrically, you mentioned earlier how this album touches on personal failure and accountability, but I would also say there’s a lot of love and personability, whether it’s as a family member, spouse, or fatherhood. Being at this point in your career, could you talk about translating the wisdom you’ve absorbed over the years into the lyrics for One Alone?

William DuVall: Yeah, it’s a lot of failure, a lot of disappointment, and a lot of mistakes. They say you get to a certain point and it’s like, “Well, now, I’ve really got to own and take responsibility for my decisions and for my life.” Particularly, when you become responsible for other people, it’s something you wake up with every day and that becomes a part of what you carry around every day.

For many years, I woke up every day with my own dreams, hopes, pursuits, and desires, and that mostly had to do with music and whatever I was doing musically at the time. It was a very singular experience and yeah, that is no longer the case. I wake up every day with my own hopes, dreams, pursuits, and music, but I wake up with the hopes, dreams, and pursuits for other people as well. Yeah, it’s a lot to carry around but you must. And hopefully, it gets lighter as you go and you get stronger as you go, and better at carrying all of it.

Has your son also inherited a similar love for music? Do you see parallels between you two or with any of the artists that he’s grown up to admire?

William DuVall: Yeah, he loves music but he’s more of a soccer player right now (Laughs). He’s really into that and I love watching him do that. I’m definitely a fan.

You went back and re-recorded some of your Comes With The Fall material acoustically. Listening to the originals and these new interpretations, you have truly been able to maintain your range, pitch, and grit. Could you talk about your vocal preparation and what has helped you stretch your range and the vast emotions that you embody through your own material, Alice, and beyond? And really, which remedies help you take care of your voice so you could channel those emotions nightly?

William DuVall: Maintaining your voice is a constant consideration and well, some might say a constant burden (Laughs). It really is a lot. Again, it’s something that you wake up with every day and you have to deal with it every day. It’s like, “Okay, am I walking into a loud room right now? Am I going into a loud restaurant where I have to yell over everyone else in order to talk to the person next to me?” And if it’s after a show, “Do I have to speak with anybody after the show or are there any guests here where I have to go and say, “Hello?” And even before the show, “Do I have press that I have to do?”

You’re always looking at your life and day through the prism of, “Okay, how is this going to affect my voice? How much talking do I have to do today?” I mean, it gets down to the point where I pencil out how many hours of silence I will have because silence is so important to me. It’s something that I’m always conscious of, 24 hours a day, “How much sleep did I get? How much care did I get this evening?” You have to be conscious of your breathing and conscious of what you eat and drink.

It is about voice maintenance but it’s really about the mind, body, and spirit maintenance. The voice is just an instrument that could convey how well or how well you’re not doing with that. It’s a constant barometer of where you are. It’s an overarching thing, “How am I doing on a spiritual or cellular level? What obstacles do I have to overcome today?”

Musically speaking, if I want to be able to get my points across musically than I have to deal with all of this other stuff. And if I’m not dealing with those other things properly, if something goes out of whack or it’s too far out of line, then I’m definitely going to feel it in my performance, or in my lack-of-ability to be able to do what I’m trying to do, what I want to do, and what I need to do. And that creates its own frustration, which could really wind you up. It’s like, in order to avoid that frustration, I need to do all of these other things and it’s a constant pursuit every day, so I don’t have to deal with that other stuff; the grief and anger of not being able to do what I want.

A lot of the time, you’re not necessarily operating on 100 percent. It might be 90 percent or whatever, you know what I mean? That 10 percent you don’t have drives you crazy. The thing for me, it’s like, “Well, let me get up to 95 or 97 percent tomorrow. Let me never get down below 80 percent (Laughs).” If you want to be the vessel for the sounds that you want to make, it comes with these responsibilities.

Your whole catalog; solo, past bands, and Alice In Chains, are so vocally intense and there’s so much that you have to give of yourself every night. Could you take me through your chemistry with Jerry Cantrell and having someone to lean on where you could bounce off one-another; and how you two approach your vocal harmonies, live and in-the-studio?

William DuVall: After doing this for a while, you actually don’t do much thinking about it. If he wrote a tune than he usually has some idea of where the harmonies are in his mind. We’ll experiment and decide who does which part. If I wrote a tune and have an idea of where the harmony is, most of the time, we’ll record it that way ourselves, so the other guy has a guiding point of how it should sound. Sometimes, you don’t have as much of an idea, so you fool around with different things in the moment.

When it comes to playing it live, we usually do it like the record. Sometimes, we might reverse parts and change some stuff over. It depends on the tune and what each of us has to deal with in terms of playing the guitar parts alongside the singing. That’s the other thing too, we have the guitar parts and he might be playing something completely different than what I am. If his part is more difficult guitar-wise, he might take the second line to sing or something like that. The same goes for me.

A lot of the time, I’m having to do some very challenging stuff vocally while I’m playing some horrendously complex guitar parts (Laughs). The same goes for him. He’ll have to sing something that is very challenging for him vocally while he’s also playing something that is incredibly difficult on the guitar. It’s like, “How in the world is he supposed to be able to do that (Laughs)?” It’s like chewing gum on a hardwire or something. But yeah, we’ll figure out whatever’s going to work best for the live show.

For the records, you have every kind of possibility, especially for the Alice albums because there’s so much layering that goes on. I mean, we might double and triple track all our parts. There’s been times where we don’t even know who’s doing what because I might double a part that he’s done, or he might double a part that I’ve done. We’re in the same exact register and we’re doing the same exact notes just to get a different timbre on those parts. So sometimes, you can’t even tell who’s who. And for other parts, you could distinctly tell who’s who because we’ve made it that way. There’s really no absolute handbook for that. We achieve what happens on those records in a variety of ways.

“All I Am,” the emotive depth in that song is a testament to your chemistry and it’s a vocal decathlon. Could you walk me through the transparency between you two and how you coordinated your respective parts and worked together to achieve that emotional melodic-ism?

William DuVall: It’s the same thing. You go into the studio and we had a template to work with because we had done a demo. We were trying to make that into more of a fully realized, three-dimensional sonic experience. One thing I remember distinctly about recording that song, Chris Cornell’s sister brought down one of his acoustic guitars that he used to sit around the house with and write songs on. We played that guitar on that song. When you hear the acoustic tracks on “All I Am,” it’s that guitar. Some of those arpeggios in there, I went in with that guitar and did a bunch of those. And there’s some strumming on there where it’s that guitar.

That was cool too because we were working so hard on that song and all of these songs and trying to get them to happen. That was just a really nice pick-me-up for what were a lot of long sessions. It was like, “This is so cool.” I was sitting there mic’d up and playing one of Chris Cornell’s guitars and who knows which songs he might have generated on this thing? And I was sitting there holding this guitar and trying to get my parts right. It really was great; it was so cool.

When you paid tribute to Chris and bookmarked “Hunted Down” and “Boot Camp” at Rock On The Range in 2018, I truly thought it was one of the classiest tributes and it was one of my favorite moments for Alice In Chains as a whole. I know “Boot Camp” is a song that means a lot to you personally. Could you take me back to coming up with that idea and moving forward with that tribute? And you’ve become part of a scene where Chris’ role was so critical. Even before you were in Alice In Chains and in the present, what did he mean to you as a vocalist, songwriter, and influence?

William DuVall: Oh man! I mean, it’s hard to even put it into words. I really did, I admired all of those records. I was part of that first wave of the American hardcore scene and the Seattle stuff came out a bit later. I started hearing about these bands coming out of Seattle that were on this small label, so I heard about groups like Green River and Soundgarden. You would see their Charles Peterson pictures where their hair was flowing and flying into the camera, and I was like, “Okay, that’s cool.” Seeing these guys grow their hair, it gave a lot of people permission to grow out their hair and listen to their Sabbath records again. I was part of that.

When the Sub Pop thing first happened, Soundgarden stood out immediately as being separate and apart and above the fray. Obviously, that was largely due to the fact that you had this guy who was able to wail like that (Laughs). It was kind of outrageous that this underground band was playing these dive bars and they had a guy who looked like that and sounded like that. It was insane. As they kept going and progressing, their records became more and more fully realized. He was one-of-a-kind and there’s really no other way to say it. I’ve been able to get to know those guys a bit through touring and meeting each other on-the-road.

It’s so funny because I’m standing right here, like 20 floors up in my room, and I’m looking over Seattle right now (Laughs). I’m looking at the city of Seattle from my window, which is kind of a trip (Laughs). But yeah, getting absorbed into that scene was definitely a heavy experience and I’ve been able to befriend these people, and losing Cornell, I still can’t believe it.

So yeah, that tribute we did at Rock On The Range was our little nod. We didn’t mention that we were going to do it to anybody. We just went ahead and did it. That was something Sean Kinney and I came up with, we had thought about “Boot Camp” and Cantrell wanted to do “Hunted Down” because he already knew that song, so we just decided that we’ll do both.

With the “Boot Camp” arrangement, we used a different type of arrangement because Cornell used to do everything in his own tunings. A lot of times, he would tune the guitar in order to write the song, like, he would tune the guitar in a way that made it easier for him to play. And that was how the song was written, so I wasn’t sure what tuning he was using necessarily, and we were tacking on that tribute at the end of our set. We were in front of 40,00 people or whatever, and you can’t really just have one guitar tuned to a certain tuning for that one song and then have both of us play it like that. You are potentially opening yourself to a lot of technical problems if you do that and we wanted this to go off flawlessly, and or at least, as smoothly as possible.

I came up with an arrangement that used our tuning anyway. We were rehearsing in Chicago and I taught that to Cantrell, so we just played it that way. “Hunted Down” was really straightforward and it was cool because “Hunted Down” is the first song on their first record, Screaming Life, and “Boot Camp” was the last song on their last record of the ‘90s and that first period of Soundgarden with Down On The Upside. It was a nice bookend and those are two songs we really like.

I wanted to mention an important point that you brought up and I’m not sure if enough people know about this part of your backstory. You were a huge part of innovating a hardcore movement in a major city in this country with Neon Christ. You originally lived in D.C. and brought that hardcore, punk demeanor to Atlanta where that hadn’t happened yet. That was something that you were in the midst of creating so I wanted to ask, what is it actually like to be part of a scene where you’re innovating a sound and influencing an entire city with that sound?

William DuVall: Again, it wasn’t that we were trying to influence the city or anything like that. It wasn’t that lofty; we were just trying to get our thing on. When I moved to that place, it was like going from color to black-and-white. All that I knew of Atlanta and all I knew of that whole region of the country, it was the stuff that you would see in the old grainy, black-and-white Civil Rights films. It was like, “Oh god, the fire hoses and the Klan cops. Good grief, what are we doing?” You know what I mean?

When I got there, again, it was a matter of that relentless drive to produce the sound that I was hearing. It was like, “Well, this is what I’m hearing and I have to find some people who will be able to do that with me.” I managed to do that (Laughs). We kind of played in the city because we were living in Decatur, which is a suburb of Atlanta., so getting into Downtown Atlanta and playing the only club at the time that would host any music like that, the 688 down on Spring Street, was a big deal.

Of course, there was another issue because we were so young, 14 or 15-years-old, that no clubs would let us play. And they certainly wouldn’t even let you go to the gigs unless you happened to be on the bill. You might get special consideration if you were on the bill. Other than that, you couldn’t even go and see any gigs, so that was a drag. In that regard, we were at odds with the law of the city at the time.

In 1983, they raised the age from 19 to 21, so it was like, “Well now, it’s even worse.” I was 15 when this started originally and trying my best to get to 19, so those guys could even give us a chance, and now the city is raising the age and they aren’t even going in the right direction. They were only making things worse (Laughs).

That was part of the thing that got us out of the 688 Club scene, and we either had to find or create other places to play. It would be a storefront, a basement, or wherever. Finally, the Metroplex happened in order to satisfy the demand, the lack-of-anywhere for kids to go experience the new underground music that was happening. It was all happening so fast and it was all about the next gig or the next song that I was going to write. And atop of that, it was about getting the band to play better and getting our band to perform above what our abilities were and being more ambitious than one thought we had a right to be or whatever (Laughs).

It was just that. It was like, “We have to make our thing. We have to make our thing. This is the band we want to be. These are the kinds of bands we want to see. This is what we want.” We wanted other bands that we liked to be able to come play. Why would anyone come to a place where there is nothing happening? We had to make something both for ourselves and to also make this a place that was worth coming to for other bands too.

There are so many parallels that you mentioned that coincide with what you’re doing now. The same mindset you had at 15, I would say it’s probably the most crucial reason that you’re doing this in your early ‘50s. It’s that relentless drive and so much more.

William DuVall: Yeah! There’s no point in living unless there’s something like this to do. I mean, there’s no point in getting up. It’s like, “What am I going to leave behind for the folks and for my family?” This is what it’s all about, you know? Try to do things on your own terms as much as you can, and maybe use this as an example of possibility for other folks to come behind and pick up where you left off. Basic things like that.

I learned a lot of really important lessons from punk rock a long, long time ago. And one of the biggest was, “Not to wait.” Wait for who? Wait for what? Wait to get discovered? Wait to get swept up? Again, it’s like, “Wait for what?” Do you know what I mean?

If you don’t do it, nobody is going to do it. Nobody is coming (Laughs). You know what I’m saying? It’s like, if you feel like you’re on an island and you feel like you’re deserted and you feel abandoned, well, nobody’s coming (Laughs). Nobody’s coming. Build your own goddamn boat, get in the water, and sail wherever the hell you want to sail because nobody’s coming (Laughs).

It’s like that, you know. I was lucky enough to learn that early on. Make your own record, be your own band, book your own tour, and create your own scene. The party’s over here. Forget about that other party over there. All of those people over there who don’t want you around anyway, who cares about them? Make your own thing.

That’s so true. Earlier, you mentioned how this album touches on some personal regrets and you’ve had some moments where you had to ask yourself, “Why?” But to sit here right now; you chose the harder path, did it on your own terms, and still found a career. What kind of fulfillment do you feel knowing that you made the outcast dream happen? There’s artistic pedigree in everything that you’ve done, and you’ve been able to maintain your integrity without compromising. What’s the most important factor in being able to follow that type of path?

William DuVall: Again, you get up every day and you just chip away at it every single day. I was doing that 35-years-ago and I’m still doing it now. The biggest thing is to survive. Most of the time, you’re operating in a space that is not very rewarding in terms of what most people think are the rewards of an artistic life. There’s no money, nobody cares, or nobody seems to care, and there are very, very few people who do. You know what I’m saying?

There’s very little magazine covers and sold-out arenas, and whatever else that you’re supposed to have; the whole party-life or whatever. There’s just you and the few people you have who will follow you into the hail of bullets (Laughs). That’s all you get (Laughs). If anything, maybe a few people will say, “You know, you’re right! The rest of the world is wrong. You’re ahead of your time and we think it’s cool.” Outside of that, most of it is very lonely (Laughs).

What the whole point is, you weren’t doing this for mass-acceptance. It’s more like, you’re doing this to get your thing on. And maybe by pure luck or happenstance, it ends up leading to a slightly wider audience. For the most part, you’re doing your thing because you’ve got to do it. It doesn’t matter what the outside rewards are, you were going to have to do this anyway. Your other choices were so much more erroneous, it’s like, “Well, looking at all of the other choices that I’ve got here, the best choice is to do what I want to do regardless of who ends up caring.”

So yeah, you live a whole life like that, and I guess you look back and there is this body of work. People caught onto some of that work much later, which is gratifying. Some of that work, I mean, who would’ve thought that I would be sitting here talking about Neon Christ 35-years-later? I never thought that. When a bunch of rough kids got together to do what we had to do for our own deeply personal reasons, we were part of a scene that influenced the whole world and changed popular culture.

I mean, my son has green hair right now. You know, I couldn’t even imagine doing anything like that when I was his age. He’s 10, and it’s because a lot of his favorite soccer players, these world-renowned athletes, have dyed their hair. When I was in school and Neon Christ was a working band, you would get kicked out of school for dying your hair like the way he has it right now, or for writing Neon Christ on your notebook. I still have adults who come up to me till this very day and tell me, “Yeah, I got suspended because I brought your record to school or I wrote your name on my notebook.” So yeah, the whole world has changed and it’s a trip (Laughs). It’s really a trip.

We weren’t doing this back then so the whole world would change and be like what we wanted it to be. We were trying to carve out a space for ourselves to do our thing without the cops shutting down our gigs or getting abused for just walking down the street (Laughs). It was very interesting, and it continues to be very interesting.

I just want to get the One Alone record out there and I want to figure out how to play some shows around it. And then I want to figure out, “What’s next?” I’m lucky enough to be operating at a pretty high level for the standards that I hold myself to, and that part is very good. It’s like, “Okay, I’m still able to do what I want to do and do it the way that I want to do it.” I could still go really hard on stage and I’m still learning how to be a better musician and performer. The learning process is still very much there, which is very gratifying. Those are the things that get me up now.