Written by Bryant Donato

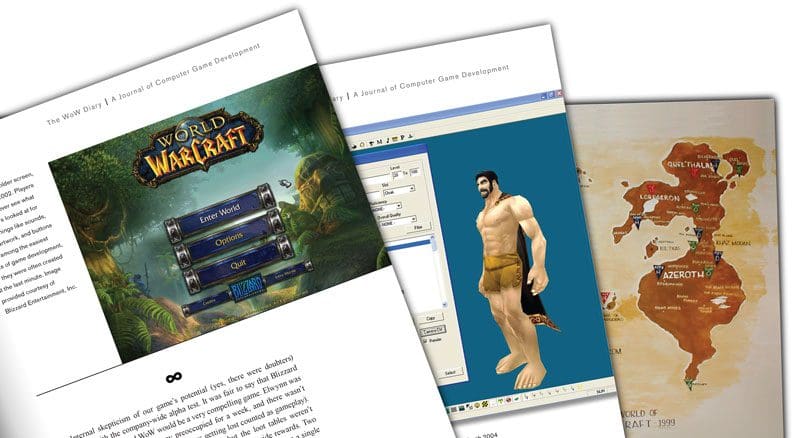

Have you ever wondered what it’s like to be in on the ground floor of a worldwide, multibillion-dollar phenomenon in the making? Contemplated on the sheer amount of blood, sweat and tears that goes into game development of such an unimaginable scale? In The WoW Diary by World of Warcraft’s first level designer John Staats, you’ll get an unfiltered, firsthand look at what it takes to be a giant in the industry.

We had the opportunity to talk to him and really pick his brain about the trials and tribulations of his experience and hope that it sheds insight into the video game industry; which has grown to be the biggest entertainment producing industry on the planet. His book is available on Amazon.com.

Can you start off by telling us who you are and what you do?

My name is John Staats and I was the first level designer on the World of Warcraft (WoW) project many years ago. I worked on the project for, worked on WoW for ten years and I was their first 3D level designer, building dungeons and castles and houses and caves and stuff. I am now the author of The World of Warcraft Diary, which is about how we built the game.

For people who aren’t aware, can you give us a quick overview about WoW Diary?

John Staats: When I started Blizzard, it was my first gig in the entertainment industry and I people spoke so well of Blizzard. All the employees love the founders of the company. And that was kind of surprising to me. But as I the first day on the job and for the next 6-9 months was so surprising how blizzard did everything differently than I expected. I started taking notes for my own education. I thought it’d be kind of interesting to write a book about this project because Blizzard’s production process is so different from everybody else’s that even though I was fairly I thought I was fairly informed as a fan looking into the industry, I was really surprised by their methodology and there was really no book that was as frank or as informative as what I was working at Blizzard.

So I put together this.

I took notes every month on where the project was and I ended up with a four year chronology of my time making vanilla WoW. And I also put together the anatomy of a development team, so to kind of see how all the moving parts and pieces work together. And I wrote it in because I’m an artist. I’m not a technical person, everybody thinks I’m a programmer when I hear my work in computer games, right? That’s just like one third of the pie. So yeah, I wrote it for the person on the street. You know, just my editors were all non-gamers. So I think it’s very approachable for a lot of people who are getting a book, whether or not they want to get into the industry. For students I imagine that would be a wonderful teaching tool especially.

What was the catalyst that made you decide I need to tell people about this journey?

John Staats: Well, the state of the game. When I first joined, it was remarkable how ugly computer games are before they’re actually made. There’s really nothing to play. There’s nothing fun about it. There’s nothing unless you think running around on the terrain is fun. That’s literally what the game was. For years, there was really no gameplay whatsoever. It was all speculation and because Blizzard, they self-publish their own games so they can kind of eat their own mistakes and they discover something really cool they can actually expand the scope of one aspect of the game. So nothing is written in stone. That’s kind of like the credo at Blizzard. And because that’s the case, there were really no design documents.

We knew we were making Everquest, but it was just such a surprising way that blizzard worked. And I was brought on board to do Dungeons. Blizzard had never made a 3D game before, and they really didn’t know how to do it. They were pumping me for information during my interview. I was actually, you know, like everyone was like, how would you go about doing this or that? And it’s kind of funny. So we were all figuring it out as we were going along. And I actually really started earnestly writing it as a narrative six months into the project. We were just throwing so much work away just because we were failing. We started out building the way a first person shooter game would build. We were using a BSP editor, which is very inflexible, it’s like Lego blocks, and it looks like a first person shooter game like Quake 3 was the engine that we would use to check out our geometry. We didn’t have an engine that could even compile our geometry. So we’re running around with rocket launchers to check out our goldmines.

It was just kind of funny and it didn’t look anything like, WoW. The process was so bad and no one had an answer to it. We really didn’t know whether or not we would even get dungeons in game, more than one or two. And I knew that WoW was going to be awesome. We had such high hopes because Everquest was a proof of concept. I thought this would be a great story to actually make because we were such we are had such a bad place. It would be a kind of a heroic, you know, feat to pull us out of the pit that we had dug ourselves from. There’s going to be this shining aha! Moment, but none of us saw any light in the tunnel and I thought it’d be a good story.

Do think that your message was conveyed the way you expected?

John Staats: That’s actually a good question because I did run the book by Blizzard, they didn’t even know I was writing it. They had no idea. I also knew their chief of staff, who was my ex roommate. And I played poker with Mike Morheim and all the founders and all the big wigs up there. So I kind of knew them. I was on friendly terms with them. I left, you know, shaking hands. We have a lot of respect for each other. And I always knew that Shane, their chief of staff now, he was the team lead for World of Warcraft with Mark Kern. He’s always been more interested in my book. Everyone knew I was keeping this diary, but he had he’d ask me like every few years, like, “Oh”, you know, “I want to see it. I want to see it.”

And it took so much time to put together, I never had anything. So I never showed it to him. I figured he’d be a good person to shepherd the book through the approval process. I gambled correctly. I showed him the book and he was pretty surprised. And one time we had a lunch together and I surprised him with the book. So they didn’t have any changes. The only thing they took out was one quote. They didn’t know whether or not to attribute the quote to the person, but they didn’t touch a single comma or anything like that. They corrected a couple things that I got wrong, that’s what I really, really wanted, because, you get a lot of things like the book is so crammed with information and details that you know. But it was good to have him fact checking for me.

So it kind of sounds like you knew you were doing something big, but did you expect, like, to have this game become such a culturally significant icon?

John Staats: I think so. We all kind of knew it was going to be a hit. Like we thought maybe, at least one hundred thousand people, which would be huge. That would be a huge amount to have playing our game, because that’s what Everquest numbers were. All their devs are driving around in sports cars and everything, so we’re thinking, “OK, that doesn’t look so bad.”

We figured we’d probably get bigger just because we knew it was more approachable. We knew it was targeted to a broader audience. And that’s basically Blizzard’s formula for success, all of their games. They target for a low end computer game system so that everybody can play. You don’t need the right beefy system and we kind of know who is going to be big. Except that technically we couldn’t actually print any more than half a million copies for North America because our servers couldn’t handle the workload of that many copies. So they sold like two or three days and we had 90 percent concurrency. It was a complete disaster. Do it was a really big hit. I was the only one who predicted that it would be have a 20 year lifespan. And it looks like I’ve under shot it. I mean, we’re 15 years later and we’re relaunching for the next generation. So what are we going to do? Where are we going to see it 15 years from now? Re relaunched again for the next generation. So it is kind of mind blowing. It actually did exceed even my expectations and I was probably one of the more “Rose glasses” person team. I thought it had a lot of upside.

So what was your favorite zone to work on?

John Staats: Booty Bay was a lot of fun because we were very concerned that we would have to hide geometry. That’s why Stormwind is so claustrophobic. We had this portaling system which first person shooters use to hide geometry. We were so paranoid that we would have a bad frame that, you know how Stormwind you can’t see over the walls of buildings if you’re in one district? They wanted Booty Bay to be like that, they really expected it to be so hard on video cards that you would never see the grand view of Booty Bay. And I was happy to see that work.

But I liked the Blackrock Dungeons. I did all the Blackrock Dungeons on the shipping game. I had such a big texture set and it just looked great. I just loved the way Blackrock Mountain turned out. It was just a very flexible texture set to work with. Sometimes you get a concept, like Blackfathom Deeps that was so hard because there wasn’t really much of a concept to the dungeon. When you only have the idea of the roots hanging down, that was it. I came up with the idea after seeing Warcraft 3 of the Wisps spinning around the roots. I’m thinking I could probably do that with this and that would be kind of nice looking. So I got one of the prop artists to make up some wisps doing that. Getting Temples visible, originally the water was supposed to be opaque and you couldn’t see any of the temples under the water which was a big win. It was a lot better looking.

Would you say that was one of the more challenging dungeons you worked on? From either a technical or creative standpoint or both.

John Staats: One of the most challenging ones was the very first zone I worked on, Ahn’Qiraj. I did Ahn’Qiraj 40, which was a raid, and I didn’t have an idea of how many monsters we would be fighting in combat at one time. Some people thought it would be more like Diablo, where there would be squads of monsters, and the other end of the spectrum it would be like Everquest where there’s one big monster that we’re chopping against. It turned out it’s a lot further on the Everquest end of the spectrum, where it’s just one big monster. We didn’t have an idea of how many people would be in a raid, we didn’t have an idea of how much space would be necessary for combat, even. We didn’t know ranges of spells, we didn’t know areas of effect of spells. Nothing. We had no party combat when I build Ahn’ Qiraj. The reason it came after is because it was so inflexible when I built it, it was my first dungeon.

I was learning this new editor, 3d Studio Max. I was completely new to it, and I really didn’t know the most efficient way to build with it. Everybody hated working with it and the reason why it was pushed back was because the designers didn’t really know what to do with it. It all looked the same, we only had about 20 textures or a dozen textures. It all kind of looked the same, it was easy to get lost, and it really wasn’t optimized space wise, for combat. So nobody really liked the dungeon and the theme of it was cool enough that I kind of wish we scrapped the entire thing and rebuilt the whole thing with a little bit more concept starting out. Originally Metzen just said “we’re not going to do full on Egyptian, it’s just temples in the desert, and bugs.” There were no layouts, there were no concept sketches, there was nothing. We hadn’t seen anything from Warcraft 3 regarding the Crypt Lord (Nerubians). I was completely in the dark in terms of art as well as gameplay. It really was a nightmare to work with.

So how was it when you were going through these areas when you were playing or as a player?

John Staats: Honestly you turn into a player and you kind of don’t care about the spaces you’re playing in, you only care about finishing the dungeon. You don’t want your group to split up before you kill the final boss so you’re just desperate to just get through the game play. It feels good. You forget how cool some scenes are, like BlackRock Depths (probably my favorite dungeon, one I’m most proud of that I built). When you don’t see something for a while, you can look at it and go, “Hey, that looks cool!” You notice stuff like that. Or if you see texture seams that kind of irk you or irritate you. That stuff happens.

So how did you feel you were able to contribute to building this immersive world? What are some of the little things you tried changing and adding?

John Staats: One thing that I did do was I pulled off doing unique micro dungeons. That was the name for our non-instanced dungeons that were, you know, caves and gold mines, mountain caves, that sort of thing, where you could just quests through or solo through. They were a lot more bite sized. Originally the plan was the game would have one gold mine for the entire game and we would just rinse and repeat that same gold mine and one cave or two caves for all the different caves. They would just duplicate the cave everywhere in World of Warcraft.

My biggest contribution to the team was showing that we could by just doing it myself. That’s why I spent most of my weekends on. It was just getting extra dungeons in the game. Like even though the instanced dungeons turned out too big, we were trying to match Everquest for size of dungeons before we realized we didn’t need super dungeons. Getting the micro dungeons was a really big win because when players are seeing the exact same layout over and over, it ruins the immersion, there’s no exploration. You know every single turn in the cave, whether or not you’re in Stranglethorne or in Winterspring. If they’re using the exact same cave with just different textures on them, then it just felt kind of cheesy. I’m glad that I was able to flesh out that aspect of the game.

When you’re creating assets that ended up not being used, were they created with future plans in mind or were they things that were there to invoke mystery? Things like the old Hyjal that you could glitch to.

John Staats: I would say 80% of the dungeons were built before we had any idea how long combat would take. I was actually pretty surprised that it would take as long as it does to kill monsters because it goes super slow. Even the smaller dungeons like Scholomance, I built it because we wanted a very quick, shorter instance dungeon. We had so many ideas. Then, as we got to the end of the project, we realized that there were only so many items we could give to players before that would just be a duplicate. If it’s a duplicate item, then there’s no reason to go into a dungeon.

So we had way too much content. We had all these ideas for other zones. And like that wall you mentioned, we knew there’d be expansions that we could just then open the door. Even in Storm Wind, we had this portal that was just there for the longest time. There’s like this portcullis stopping players from going through this wall into another neighborhood. That was our idea for player housing. And we knew that in some way, we had the idea of player housing and we didn’t know what the gameplay was, but we just put it up there and then forgot about it. And we knew that later down the road we’d have, player housing.

One of the programmers was talking about how a bridge on an aircraft carrier will have just empty space in the middle of the bridge. And it’s for computer systems and technology that hasn’t been invented yet because the aircraft carrier is going to be around for decades. We have no idea what systems it will be, like a detection system that hasn’t even been invented yet. And I have the foresight to project and say, OK, let’s put a little room in the bridge, you know, for whatever happens to be invented and that we were doing basically the same thing. When we had content that we didn’t need, we would say, “OK, let’s cut this off and we can release it in an update or an expansion.”

So what are some problems that you had to solve with creative solutions like either due to engine limitations, design limitations or time?

John Staats: Oh, I can go straight to Razorfen Downs. So Razorfen Downs, somebody showed me how to do the loft object in 3DS Max. And that’s a real technical term for projecting a texture along a spine. That was basically how you get the three dimensional thorns. Very easily, very quickly. But we couldn’t figure out the canopy. The concept for razor fin downs was obviously the Quill Boar, which is a totally cool monster that Chris Metzen came up with. And he had the idea of this this dungeon, a bunch of trenches and stuff inside a big rosebush, like a big thorn bush. That was the containment because dungeons have to be contained into their own little world. So that’s what his concept was. Without that canopy over it, it just felt like you were just on the exterior terrain.

We had limitations and how big an object could be in our game. We had polygon limitations. Like if you made that canopy in actual geometry, it would just be so much. I mean, it would probably kill your frame rate. And we also had far clip issues so that your game engine wouldn’t draw the entire canopy if because it was so big, like it would clip out and you’d only see like a hemisphere of the canopy and then beyond, it would just be sky. It’s terrible looking stuff.

So I’d gone around and around and around and as a level designer, you’re the conjunction of programing design, art and concept, and you have to be an advocate for all four of those type of fields because often they conflict. When the programmers say, no, it can’t happen, you have to ninja stuff in or hack it in to make it happen within the parameters that the engine can handle, because you’re an advocate for the concept as well. The programmer, Scott Harton, who wrote the engine, we tried to work something out that would actually work. It doesn’t have a huge impact on the game. Like when I was able to ninja transparent water into the game for Black Fathom, that had a huge impact in the game.

But that was like maybe a week or two of drama of getting that. The canopy of the Razorfen dungeon took off and on, maybe half a year worth of just once in a while trying a new thing and it didn’t work. We’d shelf it and then we think about something else and we’d try that. And that didn’t work. We tried something else. So I was kind of happy to get that in. And every dungeon is different. They all have their set of problems.

John Staats: The player run a wrong along the parapet while viewing the outside world. We felt that it was going to be the coolest thing. And the producers were like, no, once you go into the dungeon, you’re locked in and you can’t see the outside world. And so what we did is we just copied and pasted the outside world around this instance of the dungeon. And so you’re actually looking out at the fake world. So that was kind of a cool thing. But, you know, these are the things that you don’t plan for, but you realize, oh, we have to have a solution for this. And that’s basically game development. Every game has that.

Let’s transition into a little bit more for the aspiring developers and designers. So my question is, is what should these aspiring designers and developers take from your book?

John Staats: The big takeaway from my book is Blizzard puts their pants on one leg at a time just like everybody else. The book really does celebrate the ugly side of game development. It’s not a whitewashed, approved by PR time type of version that you usually see in a publication about a company, any company. It’s about the debates, the lucky discoveries, the failures, the the uncertainty that every dev team goes through, even at Blizzard. You would figure they’d have everything figured out. But every single game presents its own challenge. And there’s really no magic there. They’re allowed to eat their own mistakes and hide their own mistakes. And they’re able to just move forward. And they’ve just got a lot of cool things going for them. As far as being able to just only release stuff that they feel is good.

So to follow up here, what’s something that stood out in terms of how they did things or their culture? That maybe someone who’s new to game development or any development be able to internalize when looking to be successful.

John Staats: Absolutely. The secret is self-publishing. That’s it. That is the secret. I talked to Mark Moreheim a couple of times, and the first time I joined the company, I asked him what’s really the answer to how are you guys so successful? And that was his answer. Everything comes from that. If you’re self-publishing, then you can work until it’s ready. You can ship it when it’s done. When you can’t improve it anymore. And most publishers and studios cannot work that way to prevent themselves from being ripped off. Because a publisher, basically, it’s a bank. They’ve got a bunch of money. Studio goes to them and say, we have an idea for a game. And you cannot tell the difference between a very talented publisher or not. So many people come and go in companies.

It’s impossible really to be able to evaluate the potential of a game until it’s actually built. And by then it’s already built. You’ve spent all the money. And so Blizzard actually doesn’t have that risk. They self-publish. They’re all gamers. And I’m actually applying that to my projects. I’m building a board game and I’m self-publishing it. I’m only going to release it if I know that it’s fun. The same thing with The WoW Diary. I was after the third or fourth draft, it was hard to read. It was unreadable because there were so many facts and details that I just couldn’t put into a narrative. And it took many, many, many, many rounds of rewriting to actually get it to actually read. There’s no incentive for an author to actually polish something to that point. Unless you’re self-publishing. And again, that’s what I’m doing.

Are there any fundamentals skills that you would maybe suggest aspiring game developers or designers that they really work on? Especially in that culture?

John Staats: Absolutely. Before I went to Blizzard. I knew it was hard to get into your first job in computer games. It’s a hard industry to break into. What I didn’t know is that it is equally hard or if not harder, to hire the right person for the job. The reason why I say that is what all developers are looking for is a willingness to redo your work. That is something that they just don’t teach in school because you do a project and then you move on. And it’s kind of the worst habit to teach students. But you as it as an educator, you want to teach a spectrum of things because you don’t know which of your students are going to gravitate toward what type of way of working.

So you want to show them a lot of different things. But what you’re looking for as an employer is someone who has a willingness to reduce things over and over on their own without asking them, without showing them that, look, it’s not good enough, you know? Go back, do it again. And your portfolio is going to go from 20 pieces to three pieces. But let me tell you, the guy or girl that has three pieces in her portfolio, she is always going to get that job offer over somebody who she can show a broad spread spectrum of 20 pieces that are only middling in quality. Those three polished pieces are what you need. Polishing is everything in the gaming industry.

It’s cool that blizzard has that environment.

John Staats: You can only get that environment if you self-publish. Some publishers, they just want a blueprint on what you’re going to make and you don’t know if that blueprint is going to produce a good game until you start going down that road and you realize, “oh, this isn’t going to be fun.” If you don’t have the freedom to just say, “No, this isn’t going to work,” then you’re dead in the water. There’s no chance you can make it. It’s not like I’ve invented this idea or Blizzard invented this idea, it probably comes from Walt Disney if you have to go to anybody. Walt Disney was really the first person who worked like that. George Lucas was like that too.

So how did your experience with level design and game development translate into the board game you’re working on?

John Staats: Well, I’m trying to do what Blizzard did with Diablo to tabletop roleplaying games. Tabletop roleplaying games are bogged down with a lot of rules. There are no casual boss fights out there. You have to have the discipline to keep cutting stuff that doesn’t actually make the gameplay more interesting. You want to keep cutting, cutting, cutting, and cutting. And I think that’s where a disciplined, seasoned designer is going to cut. They’re not going to add to their vision. And it took me three years to get to the point where I just keep cutting stuff until it moves along. So that’s really that’s kind of my best advice.

My biggest takeaway is just cutting out what doesn’t work and keeping, the core of what you’re working on. I actually took out (dungeon) layouts because I couldn’t figure out how to make them interesting and have an impact on gameplay. I had some ideas, but I realized that as much as I’m a level designer, that’s not where the rubber meets the road. It’s about fighting the boss. Like I have these little boss fights. That’s basically what my game’s about. Just knowing what the core gameplay is, keep your eye on the prize.

Is there anything else you want to let anybody know? Any closing remarks?

John Staats: The book is available on Amazon.com. And if people want a PDF, if they can get it at www.thewowdiary.com.