Written by James Barry

Jackson Pines is a duo with roots entrenched in the primordial depths of New Jersey soil. Down in the dark loam, they dwell with the bones and the trapped howls of yore. Named after the woods they call home; they remain inseparable from space as they traverse time.

Over the past few years, Joe Makoviecki and James Black have unearthed folk tunes crafted in the Pine Barrens; regional songs buried within a musical time capsule. Their discovery of a rich Pinelands history, of the people who lived down the dirt roads in South Jersey and the songs they shared, made the duo the subject of a PBS documentary released this year.

Yet they aren’t confined to local tradition. They write original songs whose lyrics draw from the sprawling reservoir of American folk, from encounters across the country, and from the hard times they’ve known in the pines. Their songs inhabit a palpable world, one filled with towering trees, struggling mothers, crumbling graveyards, the ghosts of lost husbands, scraggly vagrants, and trusty pick-up trucks. Digging up tunes from centuries past, they find it eerie how similar they are to their own. The music they play seems to be as permanent as the pines.

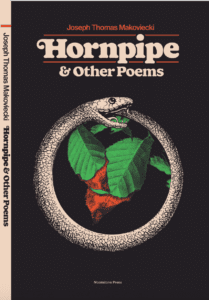

Makoviecki is a writer with more than music running through his blood. He has been compelled, propelled to write since he was a child. From poetry to short stories, to a satirical novel written during a dull history class in high school, he has poured his mind onto pages in myriad forms. He draws from a diverse literary tradition spanning the works of E.E. Cummings, T.S. Eliot, Edgar Allan Poe, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Kurt Vonnegut, Sylvia Plath, and more. His first published work of poetry, Hornpipe & Other Poems, was released in August through Moonstone Press.

I was fortunate enough to chat with Makoviecki a few days after Jackson Pines’ set at the Wonder Bar. We dove into his musical beginning, the undying aura of the Pine Barrens, his lifelong relationship with literature, and the shifts in perspective that come with age. An admirer of craft and a student of history, he spoke about the figures whose works inspired him to create. And he reflected on the piles of brash juvenilia and abandoned manuscripts that preceded his first official authorial debut. A serpentine path through life has provided him a bit of wisdom, one he willingly shared: “Sometimes the long road is the better route.”

Editor’s Note: Jackson Pines performs their last set of 2023 on September 16 at Albert Music Hall in Waretown, NJ.

You’ve been playing these folk songs for a few years now, but do you still listen to new music?

Oh, absolutely. I listen to more new music now than I had over the past 10 years. We spent a lot of time listening to music from American history, whether it’s folk music, soul music, blues, jazz, rock and roll, you name it. But in the past year or two—probably because my little sister keeps me up on what she likes—I’ve been listening to a lot of new stuff.

But we definitely have our ear to a lot of older music. For example, on Monday we played nine songs and three of them were old folk songs. But the way we play old folk songs, they feel indistinguishable from our original songs. Sometimes people can’t tell the difference. They’ll think one of our songs is really old and then they’ll think a folk song is one of ours—like the song “Mt. Holly Jail” we played on Monday. That song is from at least the 1800s in Ocean County, New Jersey. The way we play it, we don’t try to do it like a museum piece. We try to play every song like our band, whether it’s from 1850 or 2023. It’s still us playing it. So, we try not to be too precious with the arrangements. We’re not what you would call traditionalists. We play some traditional music, but we’re always playing it in a modern way.

“Hard Times in the Pines” was one of those songs that was indistinguishable from folk music to me.

And that’s from our first record. It’s one of our favorite tunes. And that’s one of the reasons why it’s our final song almost every night. Because that is our contribution to that lineage. What’s so interesting is “Hard Times in the Pines” was one of the first songs I wrote for Jackson Pines. And at that time, we hadn’t learned the New Jersey/Pine Barrens folk songs we are playing right now. We had only learned those songs in the last year and a half. But “Hard Times in the Pines” has a lot in common with all of these other Pine Barrens songs, but we had no idea. So without knowing it, we were channeling and writing similar music to what people had been playing for 150 years in Ocean and Monmouth County. It’s ghostly in a way. We’re learning songs from the 1940s right now for our next version of Pine Barrens. We’re going to record it early next year and put it out next year. And there’s this song called “Ocean County Blues” that has almost the same chords as “Hard Times in the Pines.” And it’s because we’re both pulling from the history of American music. But it’s just so strange that two groups from Ocean County, 80 years apart, made the same thing without knowing each other.

Do you see connections lyrically as well? Between original Jackson Pines songs and New Jersey folk songs?

Yes, in different songs. For example, they have “Depression Song,” which we played at the Wonder Bar. That is a song written by a gentleman who was born in the 1910s about the 30s being hard times. “Things were mighty tough down in the pines” is the first line. And then I was writing in 2015, “Listen, people I’ll tell a tale about a time and place we all know well. Because it’s hard times in the pines.” Different music for the two songs, but similar lyrics. And then his son wrote “Ocean County Blues,” and it’s very similar musically. And that one is about how he had to leave the Pine Barrens and how he misses it. And he thinks about where he grew up, even though he doesn’t live there anymore. So that’s a nostalgic song.

We have a song like that too called “Walking Back to Jackson.” It turns out there’s something about people from the woods of New Jersey. We tend to do some similar things. And I don’t know why. It’s probably because of the influence of where you grew up and the music your parents listened to, and your grandparents listened to. And also your attitude, because that’s what makes New Jersey musicians different from musicians from other areas. We sometimes don’t get the same respect as musicians from New York City, or Nashville, or Texas, but we have the attitude and the hard working ethic to dispel those attitudes. So, that might be something we have in common with musicians from 80 years ago without realizing it.

Do you find yourself drawn to songs and poems of place?

For sure. Folk music, just by the nature of what it is, is very territorial and geographic. Think of Johnny Cash, “I’ve Been Everywhere.” He didn’t write that one, but he sang it and represented it. That song lists about 100 different places he’s been to. That one is purely about going from town to town. “Hard Times in the Pines,” that’s right there. Our first album is called Purgatory Road, which is a road off of Route 70 halfway between where I grew up and Philly, where I live now. That’s a geographical touchstone. It’s not all we write and sing about, but it’s always there. Part of who we are and what we sing about is where we grew up and all the places we’ve traveled to. So, when it comes to being drawn to stuff, yes, absolutely.

Talking about poetry, I recently published my first book. I’ve been writing stuff beyond songs since I was a kid. I wrote a novel when I was in high school, it helped me get into college. But it was never published officially. So, this year, my first book published by a real publishing company came out. And it’s based around one really long poem, about 70 pages long, called “Hornpipe.” And that is situated in place and space. It’s about a character who wanders into the Pine Barrens, into the woods, who has this transcendental experience. So, in that book are locations, roads, ghost towns that don’t exist anymore, stories, folklore, a lot of music. But it’s a poem about three generations of a family through the perspective of the woods not changing and music always being in the background. So, I guess the place is a huge center point. My favorite poet is T.S. Eliot and one of my favorite poems of his is called “Four Quartets.” It’s four long poems that together make a book-length poem. And each one is about different areas. Each one has a place. So, I can’t deny places and spaces constantly pop up in our songs and in my writing.

It seems you enjoy narrative poems and songs as well. My favorite T.S. Eliot poem is “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” And that one is narrative. Your song “Purgatory Road” comes to mind as an example, with the mother and Jean Baptist, the preacher, serving as characters in a story.

The musical end of where we come from is the American folk tradition and American rock and roll. But, lyrically, where we come from is the singer-songwriter tradition. We get compared a lot to James Taylor, Tom Petty, and Bob Dylan. Not that we think of ourselves as great writers, but people compare us to them because our songs have stories, characters, and settings. Not every song, but most of them. And they kind of inhabit this overarching world. So, most of the songs are stories. I’m not always the main character, I sing from different perspectives. We meet people on the road and tell stories they’ve told us, or we sing about things we’ve experienced when we’re home or away. We do have songs that are more music based, and the lyrics take a backseat. But, if you stream Jackson Pines, you are more likely to hear an impressionistic story, or a straight up story song, not as much “Oh I love you baby, baby.” Even though we do have love songs as well. They just happen to take the shape of short stories in song form. Which I guess comes from the fact that I do write prose as well.

It sounds like you wrote prose before you wrote poetry. Is that true?

It kind of all started happening around the same time. I may have started writing poetry first. I started to fill notebooks with this style of poetry I thought I was inventing, but really I was just influenced by E.E. Cummings, and other writers like him when I was about 11. I filled two or three notebooks one summer—and I never did anything with these, I still have them—but I started writing these poems I called verses, which is interesting because a verse is part of a song, or a poem.

Around that time, I started trying to record myself for the first time playing music. And I didn’t have a laptop, this was before they were highly accessible. I had two boomboxes, and I would play into one boombox and record on a cassette tape. Then I would take it out and play it out of another boombox and put a second tape into the first boombox with a microphone and hit record so I could sing over the previous track. Then my dad got me an eight-track recorder when I was 13 and it changed my life. I started recording myself in my bedroom. And I made maybe seven or eight albums between eighth grade and high school. Then my band started going to real studios. That band was called The Boy Judas, when I was 17. That stuff is still on YouTube, my bands from high school. We were like a rock and roll indie band. And I just kept going from there. So, really poetry first and then lyrics second, but right around the age of 11 or 12. And they weren’t great, but they were songs. And my friends wanted to play them with me, and it continues up to this day. It all started there, in Jackson, in my bedroom with boomboxes.

What fiction were you reading that made you want to write a novel?

When I was young, I was really into Edgar Allan Poe. And that got me into writing poetry at a young age, and started on the track where in school, I would write a poem and the teacher would tell me to submit it to something in Ocean County. And one time I won. And it was very encouraging to go to City Hall and read the poem in front of people. I read a lot as a kid. I was really into reading popular science books. I was into books about astronomy, the universe, and astrophysics. I wanted to be a physicist first. But I always wanted to be a musician before that, so it came back around later on. But I started by reading people like Michio Kaku. And then I really got into novels by reading Kurt Vonnegut and Dostoevsky. He’s the one who really sparked me into thinking I could write something, because I read Notes from Underground. Dostoevsky is known for two of his longer novels, which are masterpieces.

I read Notes from Underground when I was about 10 years old. My sister was in college, and her boyfriend gave it to me. This was an 18 or 19 year old guy giving a 10-year-old this really heady novella. It’s only about 90 or 100 pages. So I read it and I was so addicted to that and reading other Dostoevsky. I thought I could write something short like that. So, I started just writing and messing around with short stories. I was also really into Jack Kerouac. When I wrote that book, when I was 15 in high school, it’s called The Imaginary Line. The big influences on that were Vonnegut, Dostoevsky, and Kerouac, as well as Sylvia Plath. The Bell Jar was one of my favorites at that age. That’s what I was reading at the time. I was reading a ton of Vonnegut, as many Bukowski poetry books as I could get, and Sylvia Plath’s poetry and prose. She was a big influence as someone who could do both. Many do both but aren’t as good at both. James Joyce started off with poetry. He’s my favorite writer now. He’s a big influence on my songwriting and the book I just wrote.

Joyce makes so much sense as an influence, thinking of Dublin and its importance in his work as a setting and a source of history.

Absolutely. Dubliners is one of my favorite books ever written. It’s so interesting that his catalog is also the development of him as an artist, and also his books are about that development at the same time. I was always interested in that. And short stories are one of my favorite forms. I wrote a book of short stories, but I just never did anything with it. Faulkner, who’s always one of my favorites, said something like (and I’m paraphrasing here), “all writers want to be poets, but then when they find they can’t, they try their hand at short stories, find out that those are the hardest of all and become novelists.” Because as a novelist, you can say 1,000 pages worth of stuff, but with the short story, you’re confined. So I was always a big fan of Mark Twain, Flannery O’Connor, and going back, of course, there was Edgar Allan Poe. So there’s a through line right there with all of those artists. A singer/songwriter song is like the short story of music writing.

You’ve got everything. You’ve got hip-hop songs, symphony orchestras, minimalist electronica. And I enjoy all of it. But to me, the songwriter song is the short story form. You’ve got three to five minutes to say an entire novel’s worth of sentiment, feeling, and storytelling in three to four verses. And that’s kind of what a short story is as a literary form; can you fit a novel into 12 pages and have it just kill you? And that’s what I always loved about those great writers. My favorite short story, actually, is a work of microfiction by Jonathan Safran Foer called, “Here We Aren’t, So Quickly.” It’s maybe three pages long, and I cry every time I read it.

What makes a story or a novel one of your favorites? Is it more so how it’s written, or what it’s about?

It’s definitely, on the surface level, the language. The way it’s written. How it sounds. What it would be like to read it out loud. Maybe when I was younger, it was about content. But now I can read a book about anything as long as it’s written well and written beautifully. Right now, because I just released my first book, I found out a classmate of mine just published his first book, and it’s a history book. And I’ve always loved history, I have no problem reading it, especially when it’s written well. But I am reading a book about something I don’t even care about right now. One, because I care about the person who wrote it, and it’s cool that he sat next to me in history, and he just wrote a history book. But two, he’s such a good writer and historian, that he has me reading a 400 page book about New Jersey high school football. So I would say it’s definitely the way it’s written that matters most.

I recently read for the first time Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf. And it blew my mind, because every other sentence could have been a piece of microfiction. And then you read them out loud, and they’re like music. It’s really hard to get both, a good sentence that gets something across that is also poetic. And it’s a whole book of that. So that’s a great example.

This happened before he passed, but I recently read Child of God by Cormac McCarthy. And that book is insane. Have you ever read that one?

Oh yes. McCarthy is my favorite.

So, I read it, and then he died the next week. I’ve read other books by him, but I had never read that one. It was one of my friend’s favorite books; and reading it I thought, you’re a twisted dude if this is your favorite. But, again, coming from the tradition of O’Connor and Faulkner, that southern gothic style…There are sentences in that book that are so heinous and so evil. But that’s the point. It’s not him saying it. These are characters he created. And then there are sentences that had me crying from laughter. That kind of work is what makes me glad all my other writing doesn’t exist anymore, and it’s just this book now, because I’m actually proud of the words and the lines. Comparing Mrs. Dalloway to my first novel, I mean, there’s no way. But there are levels to this craft. You can reach those heights. And it’s so inspiring, I’m just always continuing to go to the next thing.

Thinking of your first two major influences: Dostoevsky and Vonnegut. One tends to write with the utmost seriousness, and the other brings such lightheartedness and good humor. Do you find yourself drawing from both of those tones when you write? Or do you tend to fall into one?

You know what, I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently. But I can’t purposely try to fix this. My lyrics are not as humorous as those of my favorite lyricists. John Prine is like the Mark Twain of songwriting. And I’m so influenced by him. We play concerts with people who do tributes, we’ll come out and do one of his songs. I’m teaching his songs to people and talking about the lyrics. We talk about his humor and how he looks at the world. A lot of that comes from perspective. And I don’t have that. A lot of our music is either very sad or very serious. Or it’s a love song, but it’s always a love song painted with melancholy.

Our themes run heavily in the tradition of singing about love, loss, and death. We sing about sickness unto death. That’s been my experience. I’ve had a lot of sickness and death in my family. I lost both of my parents within nine years as a young man. And our music is about that darkness being examined and shown in light as opposed to being hidden and pushed away, how the expression of those stories can be healing. Not that our music is purely psychological, therapeutic music, for me or for others. But there’s a lot of that in there. Not every song is going to be about my experience with death. But there’s going to be a character dying, or a dead man or a ghost in a good percentage of the songs.

That’s the milieu we’re in, the things we’ve experienced. Friends overdosing left and right when we were teenagers. Parents dying. We’re just writing from what we know. It’s important as a writer to be imaginative but not a bullshitter. That’s the difference. You have to be imaginative, but you can’t grow up in middle class, central Jersey and pretend to be a farmer in folk music. There are guys who do that. And there are guys who don’t. We’re the guys who don’t. We write about our reality. That’s our folk music. And this is all to say, I wish my songs were a little funnier sometimes. But I’m also not a stand-up comedian. So, I’m not going to try to be funny. Because there’s nothing worse than someone trying to be funny. But we just write from what’s real.

When writing fiction, do you find yourself using a different voice? Are you able to incorporate more humor when the subject is imagined?

For sure. Not in the poetry as much, maybe a little bit. More in short stories. And writing the novel in high school and the two I attempted but never finished. That’s the Vonnegut side, that’s where his influence shines. A lot of that stuff is satire of culture. The novel I wrote in high school was about the local music scene, but I took everything and blew it out of proportion. It was the time of screamo and metalcore. My Chemical Romance was brand new. All the people in different towns would go to different shows and fight each other, and that’s what the book was about. Different bands and different scenes getting into fights. It was very satirical of how everyone thinks they’re the best band and people are all doing drugs and cheating on each other and going to parties. So, yes, it’s in the prose.

Do you re-read novels?

Yes. Absolutely. Especially the ones I love best. I just recently reread a lot of Salinger that I read in high school. Nine Stories is probably my favorite book of short stories. And when I was young, the stories I liked the best are now my least favorite. I still like them, but the ones I didn’t get, now that I’m older, I appreciate them. Because he was writing on two levels: he was writing for teenagers and adults. And not writing kids’ literature or adult fiction. He was just writing. And I can’t wait to reread Ulysses. That will be my third time reading it. That’s probably my favorite book ever.

Is there anything you read once and disliked, and then read again later on and found you enjoyed it?

That’s a really interesting one. That happens more with songs on albums. Maybe it’s that you didn’t play it out, and you crave something new. Or maybe it’s just something you have to sink your teeth into and understand. But with a book, I don’t really know. I can tell you there are books I liked and then reread and didn’t enjoy at all. But that’s not as interesting…You know what, books that were assigned as summer reading back in high school, at the time, I thought I was reading the coolest stuff. I was like, I’m reading Jack Kerouac, I’m reading William S. Burroughs, I don’t need to read this British book about young schoolboys.

Like A Separate Peace by John Knowles. I did not like that book at all when I first read it. I thought it was stupid and boring, just about a bunch of rich white guys in this upscale school. And I never read it again. But I bet, I have a hunch, if I read it right now, one of the things in it would probably make me cry. But at age 14, I just wanted Jack Kerouac riding across the country, listening to jazz, and Naked Lunch, people shooting heroin, just the most bombastic stuff I could find. But then you get older, and you realize subtlety is actually a really good currency. And books that maybe don’t jump out in your face and tap dance for you, but make you read them, might be the ones with a little more meat to them. Not to discount beatnik writers, who I love, but there’s a reason why you get into them as a teenager. Because they’re very flashy and fun.

What’s an example of one of those songs you didn’t like at first but grew to love?

It’s not that I didn’t like them, it’s that I had an album I loved. And it was my least favorite song on the album, so I’d always skip it. A simple example is The Beatles’ Let It Be. I always loved the rock and roll songs on Let It Be, like “One after 909” and “Dig a Pony,” the fast and upbeat ones. I never liked “The Long and Winding Road.” It sounds like your parents’ AM radio, you could fall asleep to it. It’s got a string section. Paul sings this beautiful melody. There’s no edge. There’s no crunch. When you’re a teenager, you want that punch. And my friends and I got really into the Beatles for the second time when we were 16 or 17, and just started smoking weed and playing guitar again. We just got so into them and thought everything they did was perfect, except “The Long and Winding Road.” I just thought it was a snooze.

And now I listen back to it, and it’s the most beautiful song on the record. It’s probably the best or at least the second best written song. Because Let It Be is actually just an album of them screwing around and having fun, which is awesome. But there are only two or three really crafted songs. And now I know what it’s about. It’s about Paul realizing The Beatles were ending, and realizing he and John weren’t best friends anymore, and things we’re going to end. And even when it ends, in the future, they’re still going to have that long road to look back on everything they did to become the most legendary band of all time.

Now that song means so much to me. Because I now have friends like that—although we never made any money and never became famous, I don’t really care about that. All I ever cared about was having a life to look back on where we could say we did what we wanted to do. We made music. We made art. We drove around the country in a beat up van. Now I have friends who I don’t talk to anymore, who I don’t play music with anymore, or who I don’t get along with as well anymore. And I see them and it’s fine, but it’s not the same. And I listen to that song, and I get it. Maybe that’s why it’s not for a teenager. Paul was like 27 when he wrote it. Maybe it’s for when you hit that age, and you start to look back at your mates from when you were 18, and maybe there is one or two you’re still best friends with, but maybe there are some you don’t talk to. As you grow older, you can fall in love with something you thought was stupid.

What’s an album with no skips for you?

Well there are so many, but off the cuff, I can easily say Fevers and Mirrors by Bright Eyes. That was my favorite record as a teenager, and it’s still one of my top five favorite records of all time. And now, as it’s starting to feel like fall outside, that’s the record for me.

If you could be the guy handing a book to a 10-year-old kid, what book would you choose?

Wow, usually I’m good at just picking something, whether I think it’s the perfect answer or not, and just letting it ride, but this is tough. I would have to say is 5 by E.E. Cummings, because it breaks all the rules, but you can read it. Some of his books are very hard to read because of his style. I can see the cover in my mind. I used to bring it to school every day. I’d say either that, or if we’re going with fiction, Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut. That’s the one that really started me off. It makes you feel like you can write. Why? Because the chapters are three pages long. I wrote my first book because of that. Having an idea is hard, but the hardest thing for people who want to write, but feel like they can’t, is developing a practice. You have to develop a technique of writing. And it’s not about what you’re writing, but how you’re writing.

When I was in high school, I had a history class that was dull, and I’d be done with my work before everyone else. And in my freshman year, everyone in class was given laptops—this was before they were a thing, nobody else had laptops in school. So I’d finish up and open Microsoft Word and start to write. And I realized after the first week, I had written five three-page chapters. And I thought it was going to be a story. Then, next thing I knew, I had 25 chapters, then I had 57, and by the end, I had 103 three-page chapters. And that’s a novel. So, it was more about knowing I didn’t have to write chapters that were 20 pages long like Dostoevsky. I just had to write something each day. And later on, I could arrange it all and edit it and fix it.

I loved all of this. Great questions and wonderful, insightful, revealing answers.