Andrew Haigh’s new film, All of Us Strangers, is the kind of tear-jerking melodrama that leaves audiences sniffling as they leave the theater. Very loosely adapted from Taichi Yamada’s 1987 novel, Strangers, by writer-director Andrew Haigh, the film follows Adam (Andrew Scott), a lonely and melancholy scriptwriter who reconnects with his uncannily young parents and becomes romantically entangled with the only other person who lives in his building, Harry (Paul Mescal).

Though the film’s runtime is relatively short, it unfolds like a flower, slowly revealing and explaining each of the seemingly bizarre features that make up its world. Adam’s ennui is given physical form in the ultimate liminal space of his apartment building, where only his and Harry’s windows give off light. Even stranger are Adam’s parents, who he seems surprised to see when he first returns home—seemingly after a long absence—and who are, mysteriously, perpetually styled like they’re straight out of the ‘80s and appear younger than their own son. At first, it seems like Haigh may be making an artistic metaphor, depicting Adam’s parents as he remembers them best or, more traumatically, how he last saw them before, perhaps, running away.

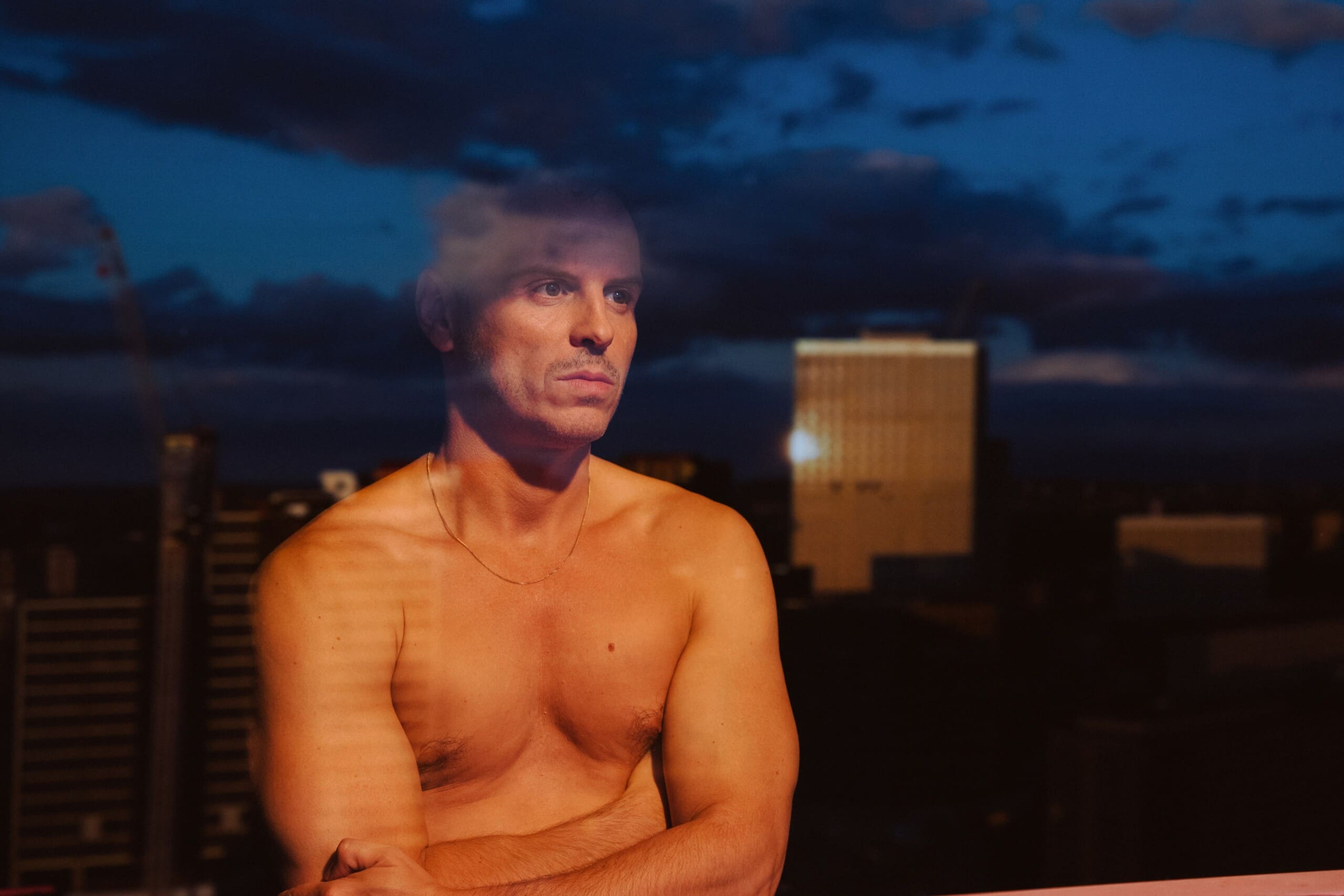

In those first few scenes, there’s a cognitive dissonance between the way Adam’s parents act and the way they appear. Jamie Bell, with his mustache and his shirt tucked into his belted pants, feels like the quintessential older dad: a little restrained, but ultimately loving. When he hugs his son or sits at the dinner table, Bell’s youthful face belies the age and wisdom his character conveys. Claire Foy, as the mother, is even better. She is neurotic, fawning and clearly so loving that it’s easy to imagine how her affection for her son could turn stifling. Still, despite how good their performances are, it’s impossible to ignore their youth, but once the film reveals its conceit, that becomes an asset and All of Us Strangers transitions into a profoundly emotional act of catharsis.

Without spoiling anything, the setup allows Adam to have the frank, healing conversations that any child would want to have with their parents—especially queer people. Indeed, Adam’s queerness is deeply tied to what makes his conversations with his parents so incredible. In some cases, like a tête-à-tête Adam shares with his father, the conversations are so perfect, so healing, that many audience members will likely cry through them. Others, like one where Adam comes out to his mother, will feel so familiarly heartbreaking that you want to turn away. Still, like all great melodramas, allowing the audience to experience those powerful emotions is what makes All of Us Strangers so enthralling.

Considering the film was shot in Haigh’s own childhood home and during filming, his own father’s dementia led to a conversation that bears a spooky resemblance to a scene in the film, it’s easy to imagine that adapting and directing the material was a cathartic experience for Haigh. Through Adam, both he and the audience get to watch the character have one moving, meaningful, best-case-scenario discussion right after the other and it feels as if a weight is gradually being lifted from our should. Which is why the closing scenes are so tonally baffling.

Admittedly, the turn the film takes in its final scenes will likely work for many. Without giving too much away, one assumes that—in a turn not taken from the novel—Haigh uses the scenes in a similar way to those with the parents, healing past wounds and mistakes with a previous romantic partner that weren’t resolved in real life. Yet the choice is so maudlin that it’s just as easy to turn on the movie entirely as it is to cry even harder. Good as the writing and acting are in those scenes, they feel like the moment the film switches from sweetly nostalgic if a bit saccharine to utterly emotionally manipulative.

Final plot twist notwithstanding, Andrew Haigh’s All of Us Strangers is a cathartic and brilliantly-acted melodrama. It features deeply-felt performances that transport the audience into its rich metaphorical fantasy. It may even become a great new piece of new queer cinema. Just don’t expect to leave it feeling entirely satisfied.

There are many gay men of a generation who among my friends find the ending very hopeful and not manipulative at all. Since most of us grew up never expecting first chances let alone second ones, the sense of “next time” pretty much constituted most of early dating (until marriage was legal) while everyone else in school got married. The idea of “not getting it right” on the first time and being skittish about who you warm up to emotionally is so commonplace and still explains why many friends are single at 50. To leave the experience and say “he’ll open the door and himself to the next guy who comes knocking” is a very authentic state to represent where most of my friends of this era live and quite hopeful/resilient. I appreciate it doesn’t work for you, but calling it maudlin and cruel is somewhat dismissive of a very large group of men’s experience…