If you’re looking for a spooky night out, Longlegs will scratch that itch.

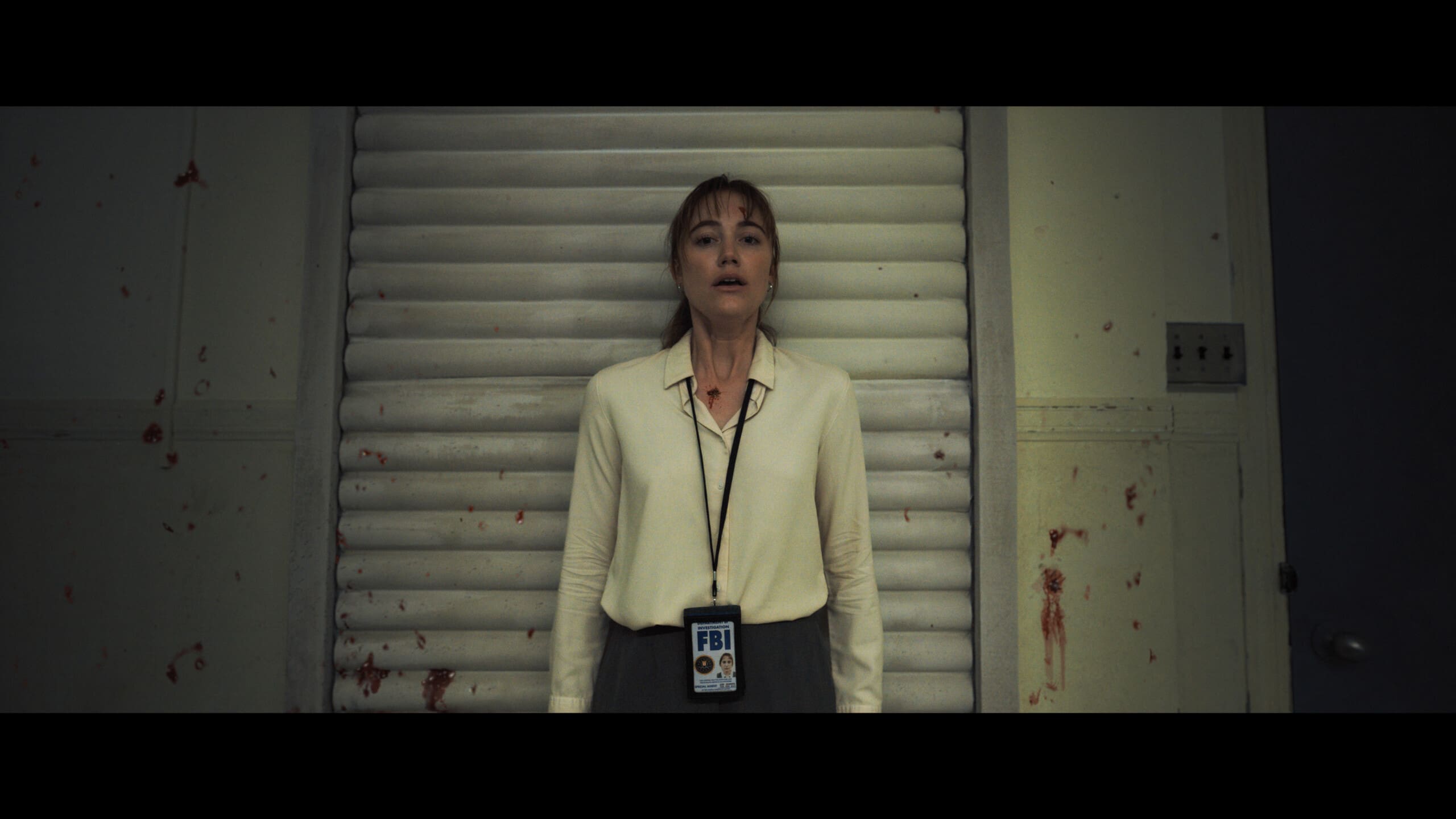

This procedural thriller with a paranormal twist wears its Silence Of The Lambs influence on its sleeves — with a strong lead performance from Maika Monroe as FBI recruit Lee Harker and the titular serial killer’s limited presence is potently unsettling thanks to both the craft and Nicolas Cage’s performance.

However, the movie has a goal that is simpler, and its effect is more haunting. Using the content within the frame to remind us of that which is outside the frame, Longlegs wants to remind you of the pure existence of evil. This reviewer isn’t an expert on director Kenneth Anger (known for his experimental films that dealt with the occult and satanism) so the comparison should be taken with a grain of salt, but Longlegs’ writer/director Osgood Perkins seems to be playing a similar ballgame, embracing an implicit understanding of film as, itself, a magic trick, that puts a spell on the viewer. You’re not simply watching the film, you’re meant to be in conversation with it. It’s speaking to you.

The conversation begins with how Perkins and cinematographer Andres Arochi frame Lee Harker, and how Monroe works within that frame. Their camera is very precise, often still, with a number of perfectly centered compositions, with Harker often their focus. An almost stupefyingly anxious person, she enters each conversation like she’s a kitten that’s come across a tiger. This can make for comic relief, like an awkward scene when she meets the family of her boss, Agent Carter (Blair Underwood). Carter’s wife, Anna (Carmel Amit) invites Lee to their daughter Ruby’s (Ava Kelders) birthday party; Harker accepts the invitation, but only after a hilariously long, uncomfortable silence. (Speaking as an autistic person, it’s not difficult to read that into the character). Moments like this, however, are few and far between, and Harker’s crippling anxiety mostly contributes to our own. If Perkins’ and Arochi’s frame is a frozen lake, then each of Harker’s trembles register like cracks in the ice. Minor, almost imperceptible, but present, and warning of a looming danger.

Even her precise motions register as a person in denial. When researching the case in her cabin, she hears a knock at her door. She walks to it, the door framed perfectly in center, and calls out to whoever knocked. In a fun little fake out, Harker reaches for the door, (a woman in my theater, sitting in the row in front of me, audibly said “NOPE” during this bit), but to lock it, not open it. Unfortunately, this level-headed attitude doesn’t last long. After returning to her laptop, she sees someone (or something) outside, and the film abruptly cuts to her scouring her property with a gun. In the background, we see she’s left the previously locked door wide open.

The juxtaposition of a precise, intelligent action, with an impulsive one, communicates a desire for control to the audience, the inherent failure of this desire, and how this failure can haunt us. In keeping with Harker’s crippling existence, each lovingly composed frame of Longlegs feels motivated by the fear of damnation. When Harker meets with her mother, Ruth (Alicia Witt), the former nun asks her daughter if she’s continued to say her prayers to keep the demons away. Harker tells her mother she never said them to begin with. Ruth responds to this with laughter. Joyous, expressive, and relieved laughter. She tells her daughter “You’re right. Our prayers don’t help us. Our prayers don’t do a goddamn thing.”

Our avenue to these fears, of course, is Longlegs himself. He’s who our prayers are meant to keep away. He bears some sort of connection to Harker, and Harker seems keenly aware that her interest in him and the investigation itself, is something she both desires and wants no part in. She can’t escape him, and even if she could, we’re meant to wonder if she would.

When Longlegs is first on screen, the top half of his face is out of frame. We’re meant to want his entire face in frame, while wanting him to get out of sight at the same time. The film slowly builds up to showing his entire face, giving us progressively more unsettling glimpses. When buying some paint, he teases (if that’s even the right word) the young cashier by repeatedly covering and uncovering different parts of his face, childishly whispering the word “cuckoo.”

However, while the film torments you in concealing his face, it’s, somehow, casual in its eventual reveal. It slowly exposes us, like the slowly boiled frog. Scenes where Longlegs is driving frame him in a profile shot, his face barely in sight, being lit by a harsh light that sharply contrasts the shadows that conceal his dark hair. These scenes don’t reveal much more of his face than we had seen previously, but his sudden screams and exaggerated facial expressions reveal more about the details of his face than we realize.

Harker sees his face before we do. It’s why she’s in perpetual fear. By the time the FBI has footage of Longlegs, they all look at Harker, realizing what she’s been going through. They don’t know how she’s connected to Longlegs, only that she is, and they don’t know what to think. Her anxiety is no longer stuck to her, but has spread throughout like a disease. Worse, though, is how the footage of Longlegs reaffirms the film’s understanding of the evil within the frame, making us aware of the evil beyond the frame, as he looks like he’s watching those who are watching the television screen he’s on. Longlegs can’t be contained by the FBI, by the square television on which they’re watching him, or by our movie theater screens.

With all this in mind, it’s best to acknowledge that any happy ending which can be taken from Longlegs will have to come from the viewer themselves, because the film won’t leave you with hope. Frankly, if you’re opposed to the copaganda that’s arguably inherent in films like this, there’s still a chance you’ll like Longlegs, because it’s so nihilistic that even when the cops do their job, nothing is gained for the betterment of humanity. With all that in mind, it’s best to ask whether Longlegs should be viewed at all. It still satisfies that itch for a spooky, fun night at the movies, but it takes you to horrible places if you appreciate it in its totality. These places are worthwhile. They’re informative and sobering, but they are still horrible. It’s just a question of whether you want Longlegs’ face in frame, or if you want it out of sight.