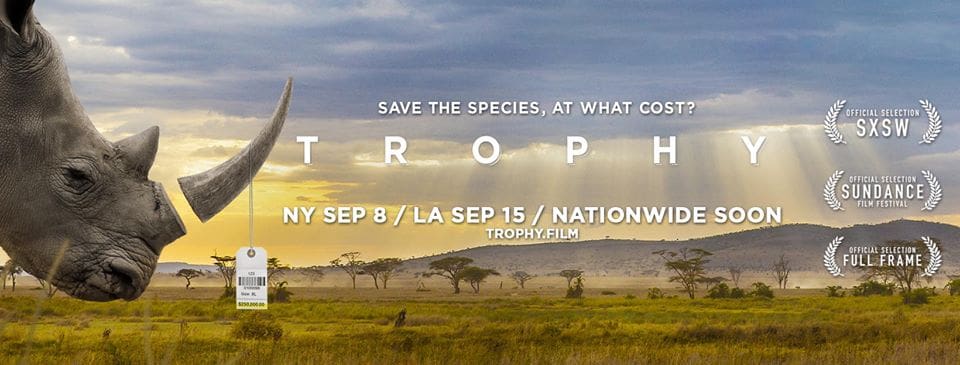

When it comes to protecting big-game animals from extinction, the solution can seem simple: don’t hunt them for sport. However, Trophy, the new film by Shaul Schwarz and Christina Clusiau is a thought-provoking film that suggests that conservation and the hunting industry may be inextricably linked. We sat down with the filmmakers to discuss what it was like to follow a big-game hunter while he stalked his prey, how they approach their subjects and what’s next for them. Read our review here.

Why did you choose to make a movie about big-game hunting and how did your perceptions evolve as filming progressed?

Clusiau: We started about three and a half/four years ago and it actually started in our kitchen. Shaul came across some photos online of somebody standing over a trophy he had just hunted and I think Shaul was really shocked. He can speak more to his growing up, but he grew up in a place where hunting didn’t even exist. He didn’t even know that you could trophy hunt and you could pay for trophy hunting. Where I grew up in northern Minnesota, hunting is a pastime. People do it all the time. I was always around it. I kind of questioned him when he screamed bloody murder, “well, why are you upset?” So that’s kind of where we started.

We went to Safari Club International, which is a big convention in Las Vegas. 25,000 people come for one weekend a year and they can buy hunts, they can buy clothing, they can buy gear. You can have AIG insure your trophies and that’s the world that’s opened up around this capitalist issue of trophy hunting. Initially, I think both of us went in thinking, “this is not right. Let’s shame this industry.”

As we started getting deeper into the issue, it was not so black and white. It was much more complex and we just wanted to peel back the layers. I think our perspective changed throughout—especially when we met John Hume. He was introduced to us as this rhino breeder–largest breeder in South Africa and the world–and he advocated for the legalization of the horn trade. He was introduced to us as this greedy man profiteering off this animal product, but what we saw was something totally different. And I think that’s really where the film started to be much more grey than black and white than what we originally anticipated the issue to be.

Schwarz: Yeah, I was definitely more anti than Christina coming in. It just disgusted me. [But] I think that’s where [things started to change]. At first, you hear this money argument [that animals will survive if they’re commodified] and you’re like, “it can’t be.” It almost angers you more to see how an industry is created around this. To some degree, you’re like, “Oh my god, this is an industry driven by psychopaths!” What was interesting as we went along and saw this more, we kind of let that go—and I hope the viewer does to some degree. [Hopefully, they ask], “what parts of this actually work and what doesn’t?” I think that’s where it got interesting.

That’s where we kind of chose to give voice to the people who believe in “if it pays, it stays.” All of our characters believe in it and, surely, we try to give them a balanced voice and show their pros and cons, but we really realized that it’s not something to just wave off. I think that’s the main change. I didn’t become a huge fan of trophy hunting. It’s not something I’m going to ever do, but I realized that maybe I can completely disagree with someone but then try to think about it a little more rationally. We always said there’s a mind and heart game here.

Have any of your subjects seen the film? How have they reacted.

Clusiau: They’ve all seen it and Philip [Glass, a sheep breeder and big-game hunter] has attended a lot of Q&A’s with us at different festivals.

Schwarz: Kind of brave of him.

Clusiau: All the characters have seen it. They all appreciate it. I think Philip is definitely in support of it. He really sees it as a platform to tell his story in a larger way and bring people together. A lot of audience members don’t agree with him and his beliefs, but for him to get on the stage and share his beliefs, I think that he feels that he can create this discussion.

Schwarz: I think for us, the goal was to create dialogue on an issue that’s so polarizing. There’s so much in this country, and the world at large, where people just scream at each other and don’t listen. So, Chris, the anti-poacher, is actually in New York and he’ll be at Q&A’s during opening weekend. Alec Baldwin is going to host a Q&A in LA on the 15th and John Hume’s going to be there.

We’re trying to engage. We’re going to have people who are very against [trophy hunting] on some of these panels, like people from the Humane Society. We’re trying to really create a conversation between the sides. Because, honestly, we feel that there isn’t a black and white, or left and right, or right or wrong thing here. The more we can get people talking–not agreeing–but at least talking respectfully to each other, that’s really the call-for-action for this film.

So, yeah, they’ve all seen it and, just to give a glimpse of Philip, we were worried about some of the things he said [in the movie].

Clusiau: Denying evolution.

Schwarz: Denying evolution was one of them. We showed Philip the film before Sundance, all alone in a pretty big room. When that part came, me and Christina kind of looked at each other. He stands up in the theater and cheers himself on. And Christina kind of leaned to me and said, “I think this went over well.” So, we don’t agree with any and all sides, but we wanted the viewer to get their perspective. And Philip, for example, had the biblical, “dominion” perspective on it. I certainly don’t think that’s the truth, but I think we made the effort to stay true to who those people are.

Yeah, one of the most interesting things about that moment is that while he says God gave man “dominion” over the animals, he doesn’t seem to consider that “dominion” might also mean “protection.”

Clusiau: Yeah, good point. I didn’t think of it that way. In his view, he is protecting. That’s deep to the core, that he really believes that. It’s interesting, because when we initially met Philip, we liked the fact that he was also a breeder and that he worked with the land and animals. So, to us, his relationship with these animals is quite different than you or me or someone who lives in a city and eats burgers for lunch, but doesn’t take care of the animals and the land. He really believes that his “dominion” is not just to trophy hunt, but to help and protect them. Being a conservationist, he thinks that, to protect them, sometimes you have to kill them.

Schwarz: He always says there’s nothing wrong with killing animals. We’ve done so forever.

Having watched this and your previous film, Narco Cultura about the drug trade in Juarez, Mexico, you guys seem to like to give your subjects enough rope to hang themselves or to use contrasting perspectives to make a point. One of the most interesting moments in the film comes when Glass shoots the elephant and he emphasizes that he’s giving back to the community, but then the locals come along and undercut that by commenting on how small the kill is.

Schwarz: I definitely try to stay true to [the subjects], but also try to show you their flaws. It was the most heartbreaking scene we filmed. It tore us apart. To some degree, as weird as it sounds, we do try to show why on paper, hunting can sometimes make sense. And then there’s reality. And in reality, Philip was set to hunt an old, dying male, but he hunted a very young elephant and that’s clearly a sad no-no.

That said, yes, the villagers wanted a bigger one, but as we were sitting there crying and hurting in shock, they were extremely happy. They would have been happier if it had been twice that size, but nonetheless, the mindfuck here is that they don’t see elephants like we do. To them, it’s a big piece of meat which is going to feed them for a long time or it’s a live animal that messes up their fields. It’s not the majestic creature we see in the West. That was the first time I saw an animal in the wild and over those couple of days, I ended up seeing this young baby die.

This issue has been like this for us from the get-go. We’re 3 and a half/4 years into it and we get in daily arguments over the good and bad and kind of end up in the middle. I think the scene showed that. You see this hunt and you’re absolutely torn to pieces, but then you’re like, wait a minute, there’s 30 times more elephants poached and that’s a much bigger evil.

The locals, the way they see it and the way hunters at least try to promote it on paper is that this is yours. We’re here visiting your wildlife to get a quota. The money and the meat trickle down to you and if the poaching numbers are too high, we’re going to stop hunting. It’s supposed to reinforce this idea that now these people are not going to kill it for meat. That happens all the time. But if they can make money and still get the meat [that’s much better]. There’s always this double-edged sword. It was a very heartbreaking scene, but to some degree, seeing the villagers made it pay off even though it was a young elephant.

What was it like following Glass on his kills? What kind of filming equipment did you use and how did you divide up the tasks? What’s it like stalking an animal for days on end?

Schwarz: A lot of it is boring.

Clusiau: Logistically, it was Shaul and I and we both had cameras. We were filming with a Sony FS7 and an FS5, but we kept the team really small, so it was just the two of us. As for stalking and walking, it’s a long process. You walk a lot. You walk probably 15 miles a day. I felt very vulnerable. You’re out in the wilderness and it’s you and the animals. You don’t know what’s going to happen and a lot of these animals are not your friends, if you will.

Schwarz: I guess to some degree, people always say it’s not a fair fight and they’re right. The hunter is more powerful, he’s got a gun. He’s got the local trackers, without whom the hunters and us…

Clusiau: Would not be able to make it home.

Schwarz: But it’s not completely un-scary, for sure. If you see elephants from a car or a big bus like most tourists, it’s majestic, not really scary. When you’re walking, they’re pretty scary. They charge and they live in herds, so it’s like a bunch of big bulldozers charging. And they run fast. There’s a lot of walking forever in the heat and going through rivers and stuff like that and then suddenly, you’re onto something. The locals did help us because we wanted to keep the team very small. Like, we had a drone, but they helped us carry that in because there’s just so much we couldn’t carry on these pretty physical shoots.

You make a distinction between what Glass does and what’s called “canned hunting” and the former at least seems to have a bit more gamesmanship involved.

Clusiau: It’s a very different model, the way that Philip hunts. It’s almost getting more and more rare in this day and age. Everything is like the South African model of conservation in the sense that, about 30 years ago, South African land owners decided that they could make more money off breeding game and selling it for trophy hunts than they could off of cattle. So it really changed the model.

Then you look at SCI, for example, and how this has become such a consumer capitalist industry, that a lot of people will save up their money to go on a once in a lifetime hunt to Africa. And a majority of those people do go to these ranches and farms–not really “canned” facilities–but smaller facilities. So it really changes the game. When Philip has to walk 15 days to harvest one animal, a lot of these guys can go to these ranches and shoot 7 or 8 animals in a week or a day. That’s quite a difference.

Schwarz: Hunters are quite ashamed of what’s referred to as “canned hunting.” They hate that name. There are certainly different grades of “canned hunting.” They’re never really shot in a cage, but they’re kind of sipping vodkas off the back of the truck and just spinning around shooting. Or the croc hunt, that’s obviously pretty “canned hunting.”

It’s weird because to me, none of this is the most ethical. So I started looking at it through the eyes of, “does this create more animals?” Can you kill one and get more? The South African ranches, as much as the hunters are ashamed and even they don’t want to protect it, it has actually been shown to be a successful model for breeders to have more animals. And to be completely fair, with the exception of lions, which to me is really disgusting because they’re living in cages, some of these animals that are hunted in Mabula, Christo Gomes ranch, they do live in pretty big areas and welfare-wise have a pretty good life. Better than the bacon we consume in the supermarket, for sure. So it kind of messed with me. What is really right or wrong? And we just wanted to make sure that people see the spectrum of hunting. But hunters like to say [ranch hunting is] tiny. It’s not. It’s a big chunk of hunting.

Clusiau: It’s a big industry.

Schwarz: And then there’s a lot of people who want to hunt in very wild places like Philip and then there’s a little bit in the middle.

Another surprising moment in the film is when anthropologist Craig Packer, who ran the Serengeti Lion Project for many years says, yes, the ranches are awful, but they’ve helped restore entire ecosystems. But you’d think he’d be the most staunch animal rights person you’d talk to. What was behind the decision not to have someone who had a more hardline view on hunting and animal rights?

Schwarz: The Born Free Foundation, we talked both to Will Travers and Adam Roberts, they’re very anti-trophy hunting. So we did give the anti a voice and we tried to do one or two scenes of the protest [outside of SCI]. But at large, that was a little less surprising [of a perspective]. We were drawn to the film from this economica perspective of “if it pays, it stays.” We wanted to feature those guys as main characters whether they have interest or they’re hunters or whether they’re anti-hunters who believe that this model helps anti-poaching. Using the technique of letting them speak, but also letting them hang themselves, that it balanced it more than to feature heavily the side that we expect. My biggest complaint with the green, anti side: they’re good about saying no, but they’re not great about giving solutions.

Clusiau: That was hard. When you look at animal rights movies, a majority [of the audience] knows that side already, so we really wanted to say that this is actually more complex than we all conceive it to be. We kind of balanced it more toward “it pays it, it stays” and the economic model and our relationship with animals. Rather than just say, “no, they’re going to preserve themselves in the wild,” because that’s what we really had thought.

The film does seem to imply a sort of naivety in a hardline, no killing stance.

Schwarz: Yeah, when we talked to one of the Born Free guys, we kind of grilled him about what he thinks about the power of breeding. Because one thing we thought of as a plus is that these things do create private lands and if people want to invest, they make money and they breed. Most of us, at least I, naively still believe that if you breed animals, that’s a good thing because there are more animals. We specifically talked about John’s rhinos and he was very against it.

Then, off camera, I asked him, “Wouldn’t you rather see rhinos without a horn than no rhinos in this world? Would you really prefer them going extinct than living on John’s farm?” He said, “Yeah, I have no problem with them going extinct.” I said, “Would you say that on camera?” And he said, “No way.” I found that a little interesting. He clearly wouldn’t make that a full on-record thing and to some degree, we’ve seen that notion again and again in some of the green organizations. Again, we’re not trying to push anyone [in a certain direction]. If you just believe that the wild should be wild, that’s great. That’s your opinion and I really respect that, but as Craig Packer says, if we don’t domesticate some or we don’t allow some of these solutions, they might be gone and you should be honest about that.

Right, the way the film reads, it seems you guys aren’t necessarily trying to make people reach a certain conclusion, you’re asking them to consider that the issue may be more complex than they thought.

Clusiau: Yeah, absolutely. Because of the journey that we took, we kind of came out with the perspective that this is more complex, that we don’t have all the answers either. I think that we created the film in a way that we wanted the viewer to do the same thing. We wanted you to come in with your ideas of what our relationship to animals is and how we use them and that you leave with more questions than answers. And as Shaul mentioned before, it was really about the dialogue.

It wasn’t so much to say, “A, B, C and D are the solutions to save animals from extinction,” it’s more that we all need to look at it and think about. In the end, we all want the same thing. Hunters and animal rights activists and normal people across the spectrum want to see rhinos and elephants and lions here 100 years from now or 20 years from now. It’s just that we don’t agree on how to get there. So, I think to us, discussion was actually the more important point than making a claim to what is right or wrong.

Schwarz: To add to that, because we kind of took what we believed was a thought-provoking, nuanced approach, both sides are a little bit, let’s say, angered or uncomfortable seeing the movie and I like the uncomfortableness. We did a screening only for hunters and I think all of the hunters expected us from New York, liberal people, just to mock and destroy them and then they saw a kind of fair shake. And when they saw a fair shake, they said, “You know what? Maybe the way that croc’s hunted is wrong. Maybe this is wrong.”

And it goes for both sides, obviously. So I think, to us, that’s the biggest reward. And it’s especially true for these kinds of films. I think we’ve seen a lot of great films in the environmental doc arena, but they seem to end on 1, 2, 3, this is how simple it is to make this better. And when it comes to this subject, we don’t believe it’s that simple and it’s not what we’re going after. We’re going after really getting these sides to talk to each other. As Christina said, we’re all trying to get to the same place. Not one side has the whole truth.

Are you guys already working on your next project?

Clusiau: Yeah, we have a number of things. A lot of the work we put off until this film came out and now we’re developing again. The next film we’re working on is called Fly and it’s about base jumpers and wing suit flyers.

Schwarz: It’s a very different film.

Clusiau: We found something really enticing and interesting in this community of people that want to jump off cliffs and fly.

Schwarz: Willing maybe to risk their lives and sometimes die for a real meaning of life and to some degree, we’re fascinated and jealous.

Trophy is currently playing at the Quad Cinema in NYC and opens in Los Angeles on Friday.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65OCUtz-aIM&t=1s