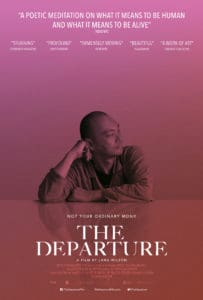

Early in The Departure, the new documentary from director Lana Wilson, we see the ritual that gives the film its title. The film’s subject, Rinzai Zen priest, Ittetsu Nemoto leads a retreat for people who want to (or have already tried) to commit suicide that he calls “The Departure.”

In it, he asks the retreaters to write down the three objects they love most, the three people and three things they wish to happen in their futures. Then, he asks them to eliminate them slowly, recreating the experience of what it will be like to lose those things when they die. It’s a powerful scene and sets the tone for a movie that is filled with quiet power.

Though The Departure‘s initial draw is the novelty of seeing a Buddhist priest who used to–and still occasionally does–spend all night going to “discos” and getting into fights, the film is actually a low-key examination of suicide in Japan. After a beloved uncle and two of Nemoto’s friends killed themselves when he was young, he became fixated on discovering what drove them to take their own lives.

Now, his work consists largely of convincing people not to kill themselves. It’s as taxing as it sounds. In one scene, we see him cry as a woman on the phone tells him that she just wanted to hear his voice one last time before she takes the pills that will end her life. It’s not remotely the only time Nemoto’s relationship with a suicidal person is mentioned and it’s also not the only time he exploits that connection to convince someone to keep living. It’s no wonder, then, that his work has taken a toll on his own health.

Nemoto has already experienced one heart attack when the film begins and he’s quickly on his way to another. Yet even after his doctors warn that his high stress levels are contributing to his health issues, he doesn’t slow down. He still smokes, he still goes clubbing, he brings his retreaters back to his temple so they can dance and sing karaoke all night. Not even his wife and mother’s worries and his son’s apparent discomfort around him seem enough to convince Nemoto to change his ways.

Indeed, though he spends his days convincing people that they must keep on living, Nemoto seems either unwilling or unable to change his self-destructive behaviors. The narrative seems almost Grecian in its potential for tragedy and if this were a fictional film, it would almost have to end like with Nemoto having a heart attack while he plays with his son à la The Godfather.

Thankfully, Wilson’s film doesn’t quite go full tragedy even if all the beats are there. When Nemoto’s big medical scare finally does come, there’s no dramatic music or overwrought voice-over. We just get his wife Yukiko’s quiet, loving admonishments as he lays in a hospital bed. The end is similarly understated. We return to the ritual that began the film. Once again, Nemoto asks the retreat members to write down and then slowly eliminate the things they care about in life. This time, however, we see Ittetsu’s final slip of paper. It reads, “my son.”

Rating 8/10