This year marks the 50th anniversary of the moon landing and the new documentary Apollo 11 is a glorious way to mark the occasion. Assembled from NASA’s own archival footage, it is the documentary equivalent of last year’s First Man: a tribute to human ingenuity that reminds us just how crazy it is that we ever dared to shoot people into the sky in a glorified tin can. However, where that film distracted from its own greatness with half-baked melodrama, Apollo 11 is a filmgoing experience so spectacular, it’s likely to be one of the year’s best.

Director and editor Todd Douglas Miller’s film is, first and foremost, a testament to the importance of film preservation. All of the footage we see comes directly from the national archives and, because the original film was basically untouched in the past 50 years, the images are in pristine condition. Miller and his team scanned the film at 16K and especially when seen in IMAX, it is absolutely breathtaking.

Some things, like the footage showing various launch stages break off the rocket, are familiar even if we haven’t seen this exact footage before. However, the new 70mm footage is the real discovery. In wide, clear shots we see the rocket clearer than ever before as it leaves the ground, the view of the sky and the light from the flames shooting from the bottom or at a much higher stage in its trajectory, being followed as it goes ever higher by another aircraft. It’s jaw-dropping stuff and sure to wow both space nerds and the average viewer alike.

While a huge part of Miller’s job involved choosing what to include (he joked during a post-screening Q&A that the first cut was 9 days long, the same as the actual mission), the rest is dramatizing what probably started as very dry footage. The stages of a rocket launch take hours and without proper editing, would be filled with mind-numbing amounts of technical language. While choosing to cut a lot of that inevitably results in some loss of nuance (an early series of montages showing the astronauts’ home lives provides the idea, but not the context), it allows Miller to create a film that has all the drama and epic scale, but none of the downtime.

One of Miller’s best choices comes near the film’s end, as Command Module Columbia reenters Earth’s atmosphere. Throughout the movie, Miller has trained the audience to expect to switch between the astronauts’ and mission control’s perspectives, but when the ground loses radio contact with the module for a period during the landing, we do too. The audience of course knows they will be safe, but the moment still manages to create a fraction of the tension the world must have felt in that moment.

Still, as Miller stated during the Q&A, spectacular as the base footage and his clever editing of it is, the film wouldn’t be quite so engrossing without the brilliant sound work of Eric Milano and the original score by Matt Morton. Miller makes the rather surprising decision to not have a narrator to tell the audience what’s happening at any given moment. Instead, Milano has to lead us through the narrative. Almost all of the talking comes directly from the archives, but most the mission recordings and film were recorded independently of each other.

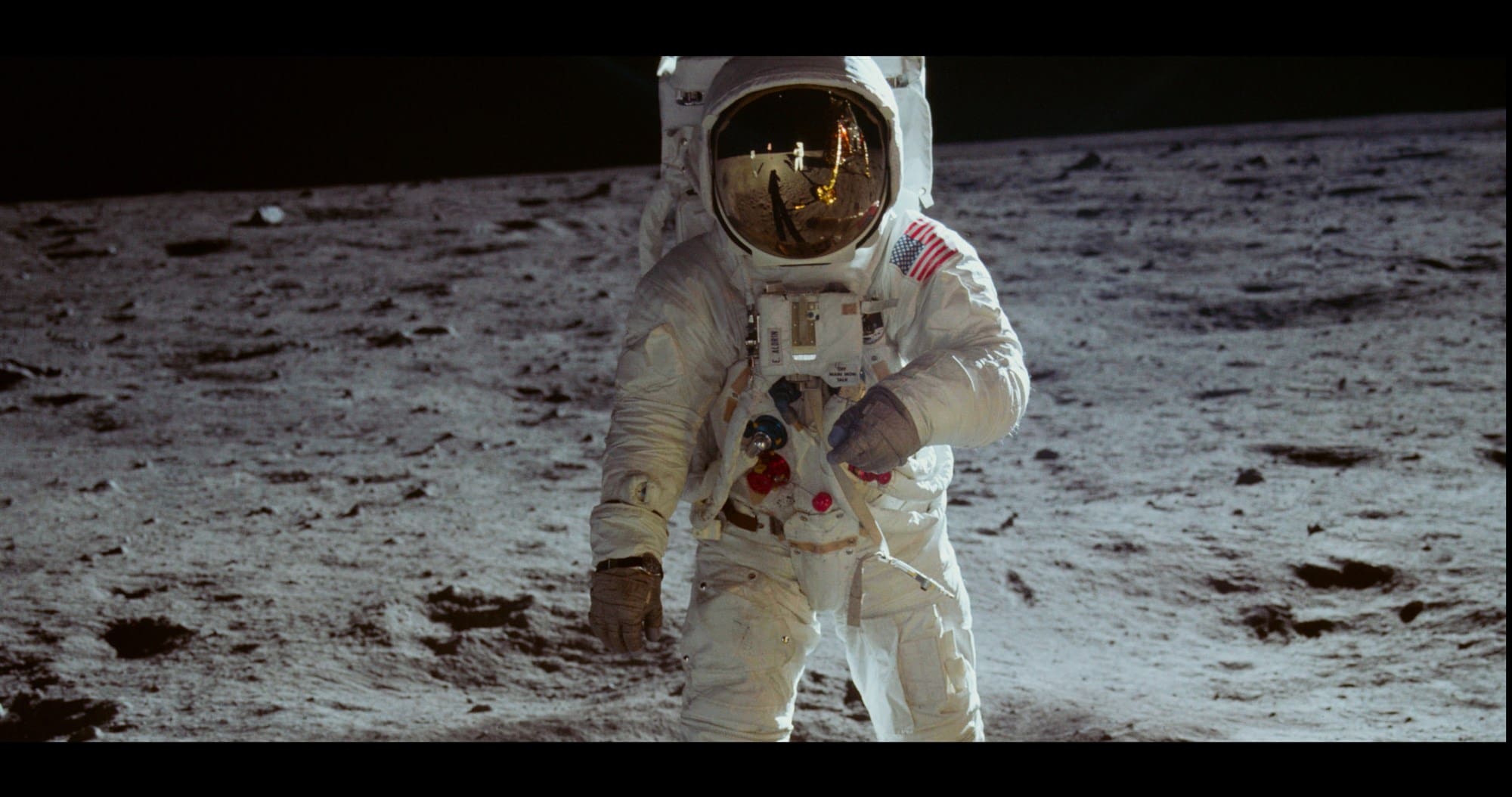

So, before Milano could even start editing that sound into a coherent narrative, he had to sync it up. As Miller explained, sometimes Milano would get lucky and the camera would show the mission control clock to tell him where in the sound recordings to go, but a lot of the work involved lip reading through 9 days of footage. The result is transporting. Whether it’s the shots of mission control or the way Aldrin or Armstrong’s radio communications play over serialized still photos taken by cameras left on Eagle while they moonwalked, the sound work is so good, it feels like it was recorded specifically for the film.

While Miller mentioned that Milano did some foley work to recreate the sound effects, composer Matt Morton’s score seems to take over some of that work while also giving the film much of its emotional weight. Though the score itself is very modern and booming, Morton insisted on using only instruments and equipment–in this case a reissued Moog modular Synthesizer from ‘68– that would have been available at the time.

One of Morton’s best sequences comes during the initial launch from earth. All through the pre-launch footage, Morton’s score builds tension—all of which comes to a crescendo as the countdown clock approaches zero. It’s a moment we’ve seen before, but instead of having us listen to the verbal countdown we’ve heard many times, Morton syncs a room-shaking boom to each tick of the countdown clock. While some could read the moment as a little heavy-handed or cheesy, there and elsewhere, it perfectly conveys the enormous achievement Apollo 11 represents.

Fifty years on, it can be easy to forget how many things had to go right in order for Armstrong and Aldrin to walk on the moon, but Apollo 11 not only makes that clear, but creates an overwhelming feeling of national pride because of it. It can be difficult to find that pride in our current political climate, but watching one of the film’s final scenes, when Miller plays John F. Kennedy’s 1961 speech promising to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade over images of the men who fulfilled that promise celebrating, it really seems possible that America was once great.

Rating: 9.5/10

Comments are closed.