There is a scene in the 2013 movie, Man of Steel where Jonathan Kent (Kevin Costner) is speaking to a young Clark Kent. He says, “One day, you’re gonna have to make a choice. You have to decide what kind of man you want to grow up to be. Whoever that man is, good character or bad… he’s gonna change the world.”

The story of Superman, or Kal-El, is one of an alien who comes to Earth and grows up to be the ultimate beacon of truth and justice. All of this, while having the power to do almost anything imaginable. He can fly, he has super strength, and even X-Ray vision. Some might say that his greatest attribute is his heart. The saying goes that absolute power corrupts absolutely, and yet, Kal-El always chooses the best path.

Now, take that story skeleton, and daydream about if it can go the other way. Perhaps in an alternative timeline that’s not connected to DC, Superman allows that same power to cause a drunken sense of superiority within himself. It’s an intriguing prospect. This is the paradox that director David Yarovesky and writers Mark and Brian Gunn pose to the audience in Brightburn. With most superhero movies, we see that the protagonists eventually band together and overcoming whatever evil is set upon them. None of them really contemplates a character choosing to lean into being an antagonist.

The setting of Brightburn should be very familiar to those familiar with the Superman lore. Brightburn is a small, rural town in Kansas where Brandon Breyer (Jackson A. Dunn) lives with his adoptive parents, Toni and Kyle Breyer (Elizabeth Banks and David Denman). They are your typical rural family that has a farm and is very close knit—that is until forces concerning Brandon’s origin start to take hold and he becomes a conduit for something more sinister. Maybe the “story book” archetype of humans who are endowed with special abilities don’t always end up being overly inspiring and altruistic.

Performances from Banks, Denman, and Dunn really shine throughout the movie. Toni is the embodiment of a mother’s love and despite her child acting out (to say the least), she always tries to see the best in Brandon. The way that the movie reveals itself to Toni and Kyle, you sympathize with them because all they ever wanted to do was be parents. The emotional chemistry between Banks and Denman really works. In the way that Brandon came to the Breyer family, there’s a divine intervention tie-in where a mother has to believe that their child’s unique qualities have to be for a greater purpose. Unfortunately, that naivety backfires abruptly and rather violently.

Dunn makes the slow descent of the murderous and power-hungry Brightburn worth the watch. It’s in his mannerisms and facial expressions that he depicts this strange space of madness that comes over him. A congruent story line that runs through is that the adults around Brandon chalk up his outbursts in the beginning to puberty.

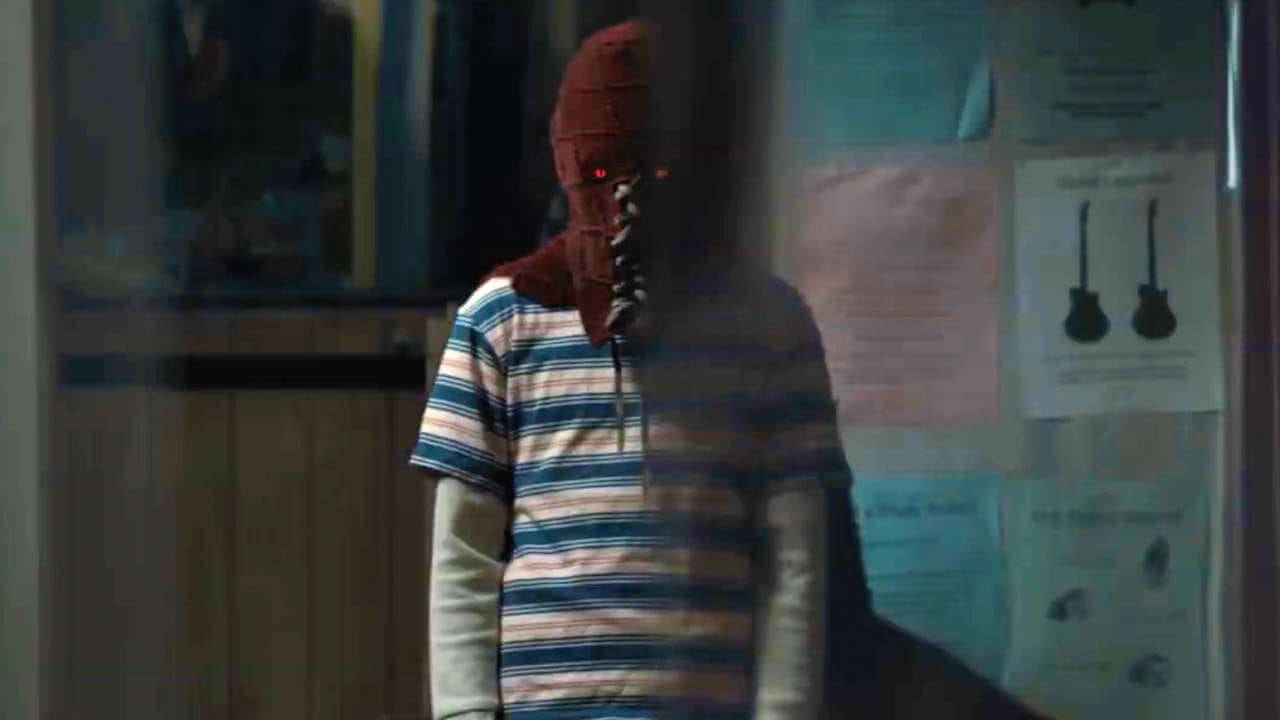

In the spirit of Man of Steel, there are some obviously homages to the 2013 film and character overall. The blue and red motif comes about often. Red is more so pushed as Brandon begins to have a grimmer outlook. The red in the mask that he wears reflects that as well. Yarovesky doesn’t particularly desire the audience to feel bad for Brandon. He is actively choosing to do these evil things in a quest to be dominant. Yarovesky wants a clear distinction between the adolescent boy who feels like a bit of an outsider and the boy who engages in all the dark parts of himself.

That’s where the horror aspect comes into play. Some of the character deaths are absolutely graphic and brutal and even a reminder of a grind house, b-movie. Brandon completely loses himself in the blood lust of this newfound power. So, almost every kill that occurs is in this over-the-top manner to show how much power he has—whether for the betterment of the film or as a deterrent. Horror fans will recognize particular camera shots that add to this sense of dread of being stalked.

The score from Timothy Williams has these callbacks to Hans Zimmer’s score where Toni and Brandon have these reflective moments. Many would recognize the piano chords that begin when a character tries to make an emotional appeal to Brandon. These are reminiscent of when Clark Kent spoke to his parents. Some of the cinematography where the sun is used plays to that, however, Brandon does his evil deeds mostly in the dark of night. He’s more akin to a Jason Voorhees.

Some drawbacks to the film are the linear timeline. Brandon sort of stumbles upon his powers. There’s no struggle or no climb to find these foreign abilities within himself. Tied in with this mysterious force that comes over him, there are hints, but the movie goes into more of a sequel tease than providing answers. Is there an internal struggle that occurs? The movie shows you flashes of this, but doesn’t really develop it.

While the overall story is contained to the town of Brightburn and how the town is affected, the backstory of where Brandon came from is sacrificed. This may be a door left open to be explained later, but the movie leads you to desire more about Brandon’s beginnings.

When you reach the end of Brightburn, it asks a good question that’s seldom heard in a realm of superhero cinematic universes: what if someone with all the power in the world didn’t choose to utilize those attributes for the betterment of something or to aspire something greater? The movie is able to take a story we are already familiar with and puts through the eyes of a 12-year-old child and his emotions. Brightburn is more of a horror film that may appeal to those who are looking for something different than the conventional superhero box despite little issues that pop up.