With his first feature documentary, director Todd Haynes creates an evocative and engaging ode to 1960s avant-garde art with The Velvet Underground. The film is based mainly on the band of the same name that became the centerpiece for the explosion of the experimental avant-garde art scene in the 1960s. Haynes is no stranger to directing music stories, as he’s made films like the glam rock-inspired The Velvet Goldmine and the fictionalized Bob Dylan film, I’m Not There.

The Velvet Underground is really something else though, as he tells the story of the titular band through a lens fitting of their avant-garde artistry — an form of art meant to be experimental, radical, and unorthodox to push boundaries and break past the norm. The mixture of rock music and this avant-garde mentality seen in the film was pretty revolutionary at the time considering most rock music was meant for dance halls. This genre, while not exactly offering great financial success still, made The Velvet Underground one of the most fascinating and influential bands in the genre and on many other artists genres for decades to come.

Haynes employs avant-garde visuals and storytelling by filling the frames and utilizing archived videos and audio clips as well as interviews with important figures of the time and surviving members of the band. Every time Haynes introduces a member of the band he employs this awesome visual of splitting the frame with this stoic visage of each band member placed next to archived footage of their story as an audio recording plays over. At times, you can almost see them reacting to their own story and it creates a more personal and impactful first impression of each pivotal figure of the band.

From here, Haynes continues this visually artsy which makes the story of The Velvet Underground and the ’60s New York City avant-garde scene incredibly engaging and unexpected. Haynes really has an approach to the visual storytelling here that defines what avant-garde was all about – taking an unorthodox approach to artistry and it pays off immensely in making The Velvet Underground a faithful ode to its subject and creates a visually unique experience. Admittedly, some of the “style” choices — particularly audio ones — can be a bit much. Guitars shredding, foe examples, takes you out of the moment and makes this not the kind of movie you want listen to with headphones when it drops on Apple TV+.

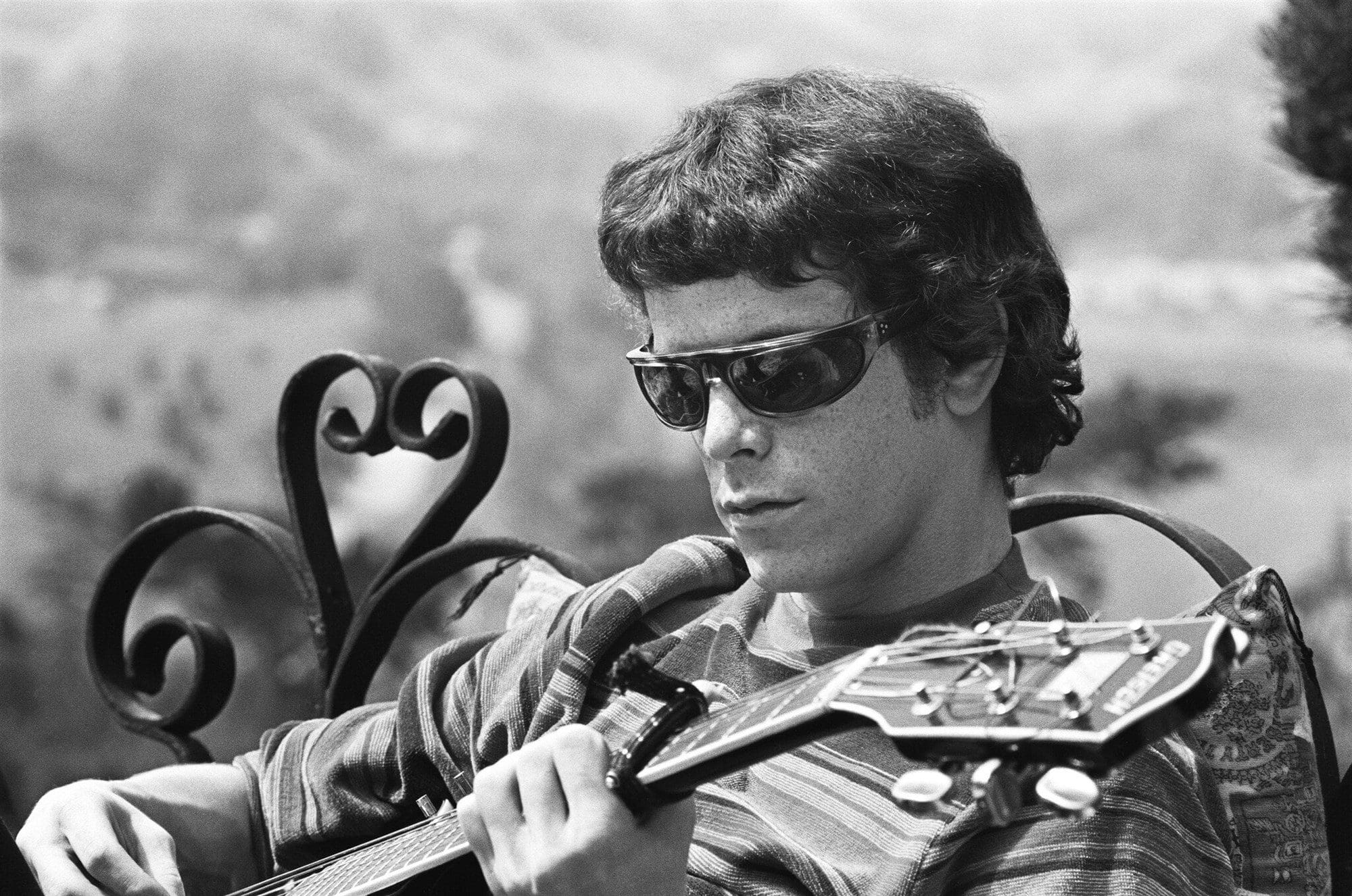

Within the visual story frame, Haynes showcases the origins, impact, and experimentation of The Velvet Underground and its members. The sequences dedicated to exploring the avant-garde influence and impact of pop artist Andy Warhol working the band’s most iconic figures — guitarist/singer Lou Reed and Welsh multi-instrumentalist John Cale — are honestly so fascinating the film could’ve added an extra 30 minutes solely about this and it would’ve been just as compelling. It’s fascinating to watch how Reed developed darker poetic lyrics — based on his own experiences exploring his bisexuality and drug use — were backed by Cale’s experimental sound and Warhol’s artsy stage management.

The Velvet Underground’s sound was so unique for the time and the added avant-garde elements to their music and stage presence makes their story of coming out of the underground so important and relatable. The way the band was so openly real and vulnerable about themselves made them this underdog voice for people maybe feeling out of the norm could relate to. There’s a point where the film describes them as counter to both pop culture and counterculture because they were so their own thing. The way that Haynes brings this out by delving into their creative process and giving a wider, more personal view of the expanding avant-garde scene of New York City really lends authenticity to their uniqueness.

This is further hammered home during interviews with musician Johnathan Richman and how the band made him feel heard. It was even interesting to hear from the band’s drummer Mo Tucker about how the group especially, almost hilariously hated hippie culture, which at the time was highly considered counterculture, which solidified the band as even more as a unique entity within American culture. Haynes brings the right pieces together to tell this engaging and personal story about breaking the mold and legitimately coming out of the underground.

Haynes gives us a great depth about the dynamic of the band and a very personal look into the main players – especially Reed, Cale, and sometimes frontwoman Nico. This whole idea of unique artistic visions coming together almost feels like watching an artsy avant-garde Avengers coming together with how Haynes depicts the chronology of the band’s existence. From Reed and Cale coming together as these two hungry artists looking for a breakthrough and then suddenly breaking apart to Warhol adding another sense of vision through his management, the film really brings you on an immersive journey with this crew. It’s an amazing celebration of this era of experimentation – for better or worse.

It’s hard not to feel at times like The Velvet Underground kind of glosses over some of the negative, even misogynistic parts of this crowd. It’s awesome that the film gives us a lot about people’s adoration towards and the true talent of Nico as an artist and especially show a good amount of Tucker – who was a true gem in her interviews. However, there’s a moment mentioned in the film about the group valuing women on their beauty and seemingly excluding them that’s not touched on enough. It’s a point that’s brought up only to have the subject change to Nico being beautiful and talented. It’s odd that the film brings this up and does nothing with it. There’s could’ve been more interviews or perspectives from Tucker or archived audio from Nico to flesh this aspect out instead of it just being a mere mention.

The film feels like more of a celebration of the band and scene and that reverence overshadows some of the more catastrophic aspects of the band and scene – mainly Reed’s outbursts and confrontational personality. It’s great to see Reed be depicted in the influential light and that his genuine vulnerability is displayed throughout the film. Yet, whenever the film tries to get into a moment about how Reed’s personal struggles cause rifts in the band, it doesn’t really know what to say about it. More often than not, it’s dismissed as “Oh, well that’s just Lou” mentality. This feels like a missed the opportunity to explore Reed’s mental health and drug issues because the film seems afraid this conversation might ruin his influential legacy. It’s undeniable that Reed is a one-of-a-kind creative mind that’s inspired and influenced so many others and talking about issues surrounding his confrontations that legitimately caused things to break apart at times doesn’t take that away from him, but rather shows him as more complex.

Despite how it uses its sense of celebration to steer clear of tough topics, Haynes masterfully creates an artistic vision of avant-garde with The Velvet Underground and fleshes out the avant-garde scene and the band smack dab in the middle of it all in an engaging and personal fashion. Don’t be surprised if The Velvet Underground becomes a dark horse documentary when awards season comes around.