Compared to much of his rather fantastic, even magical, output, director Guillermo del Toro’s latest, Nightmare Alley, is relatively straightforward. Based on William Lindsay Gresham’s novel of the same name, it follows Stanton Carlisle (Bradley Cooper), who joins a traveling carnival only to become fascinated by its world. While there, he learns the secrets of mentalism from fortune teller Zeena (Toni Collette) and her washed-up, alcoholic husband, Pete (David Strathairn) and begins a romance with Molly (Rooney Mara). Armed with this lucrative new skill, Stanton and Molly leave the carnival behind and cater to higher class clientele, but when they cross paths with the sharp Dr. Lilith Ritter (Cate Blanchett), Stanton soon realizes he may not be the true master manipulator.

Though del Toro has dabbled in many genres from horror to comic book adaptations to sci-fi romance, noir is basically new ground for him. And while his detailed, juiced-up mise en scène may not seem suited to the noir’s grounded, chiaroscuro style, his affinity for the fantastic lends itself well to Nightmare Alley‘s slightly mystical world.

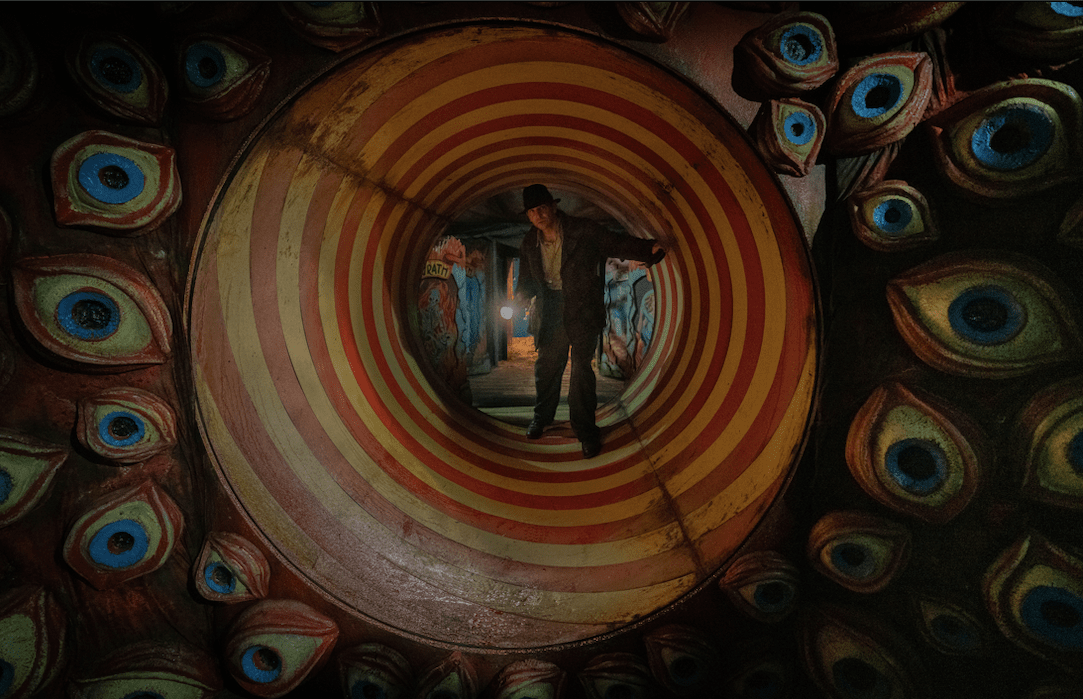

There’s certainly a griminess to production designer Tamara Deverell’s take on the carnival, but it simply masks a vibrant and somewhat off-putting beauty. The house of horrors is filled with distorted mirrors that shine dangerously and a large red devil face that menaces from above. Costumer designer Luis Sequeria’s clothes are appropriate to the film’s 1930-’40s-era setting and the lifestyle these characters lead, but they’re also too clean, too on-the-nose for the archetypes these characters fit into. Zeena looks like a quintessential fortune teller, Molly like an ingenue waiting to be plucked from her low upbringing and Willem Dafoe’s Clem the exact kind of con-man you expect to see running a carnival operating on society’s fringes.

However, while there’s an unmistakable polish and artificiality to Nightmare Alley, it’s never anything but an asset. Rather, where del Toro’s adaptation fails is in its narrative. Those failings perhaps wouldn’t be so glaring if it weren’t possible to compare this film with a previous adaptation from 1947 directed by Edmund Goulding. Despite being almost an hour shorter, the 1947 version manages to deliver all the same shocking story beats in addition to a slightly different ending (presumably required under the production code to make the overall message a touch less bleak). Still, the new film’s slower pace and more faithful ending wouldn’t necessarily set it below the first adaptation. Rather it’s the way del Toro and Kim Morgan’s screenplay subtly shifts the narrative’s focus that ultimately hamstrings the film.

Tyrone Power plays Stanton in the ’47 version and while the role fundamentally changed his image, the film is essentially a showcase for its core trio of actresses: Joan Blondell, Colleen Gray and Helen Walker. Del Toro’s cast is even more stacked, with Collette, Mara and Blanchett taking over for each actress respectively. While Blanchett gets to chew through beautiful Art Deco scenery as the femme fatale, Collette’s role feels almost like an afterthought. After one great seduction scene the first time she meets Stanton, she’s little more than a plot device for the rest of the film. Granted, Blondell’s version of the character served similar narrative functions, but that take also allowed Zeena more agency within the narrative while also giving the audience a better understanding of her history and motivations. As is, it’s a wonder Collette took such a small and simple role.

However, the biggest victim of this shift is Mara’s Molly. In both films, the course of Stanton and Molly’s relationship reflects his gradual corruption. When they meet, he’s ambitious but seemingly well-intentioned. There’s promise of a better future in their coupling. As he becomes more practiced and successful at deceiving people for money, the unhappier she becomes. The problem here, however, is that we don’t really understand why. We assume that she’s upset over the way Stanton’s ambition hardens him over the two years of their marriage, but we’re given no idea of what she wants in life outside of Stanton being less of a charlatan. Rather, Molly, like all of the women really, is simply a pawn in Stanton’s story.

What’s left in this refocus is Stanton’s journey and Cooper is, unfortunately, not up to carrying the film. There’s no question Cooper is a movie star and his charisma is often well-used here. In a scene where Stanton manipulates a town sheriff into not shutting down the carnival, Cooper’s skills are at full power, making it easy to understand how anyone could be taken in by his smile. The same is true even as he goes toe-to-toe with Blanchett, who is so good at playing a femme fatale at this point that she could probably do it in her sleep. Where Cooper’s characterization fails, however, is in convincing the audience of the story’s most essential arc: Stanton’s fall from grace.

From the opening moments, del Toro and Morgan’s script paints Stanton as someone not quite on the level. Though Power’s take on the character was also driven by ambition, there was also an essential goodness there, something to corrupt in a way Cooper’s version of the character simply doesn’t have. Rather, Cooper’s Stanton is mysterious and potentially dangerous from the beginning. So, his slow corruption feels predetermined. While that inevitability is part of the story’s bleakness, it also lessens its essential tragedy. Instead, the film’s pace is so slow and deliberate in going through the motions that it dampens some of the narrative’s inherent tension.

Guillermo del Toro has always been an impeccable visual storyteller and Nightmare Alley only reinforces that. Where it fails is in its narrative and therefor its ideas. What should be a film about the depths of human depravity and deception becomes a lifeless painting, enthralling to look at but lacking in substance.

Comments are closed.