It’s been over a decade since we’ve seen a film from the legendary Hayao Miyazaki, the director who’s helped make Studio Ghibli a renowned force in animation with films like Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, Howl’s Moving Castle, and Princess Mononoke. Now, Miyazaki returns with The Boy and the Heron—for what could be his final film—and delivers a culmination of his best elements as a filmmaker.

Over the years, we’ve seen animation, both American and Japanese anime, transition away from the traditional hand-drawn style and shift towards either 3D computer-animation or a mix of the two. However, Miyazaki goes back to his iconic hand-drawn aesthetic for The Boy and the Heron and it’s a very important aspect to the film being Miyazaki’s potential swan song. This style is a key identifying trait to any of his or Studio Ghibli’s films and a big reason that they’ve stood apart for so long. So, it’s only fitting that Miyazaki’s potential final film sticks to that style and it’s something that’ll give fans of Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli instant gratification.

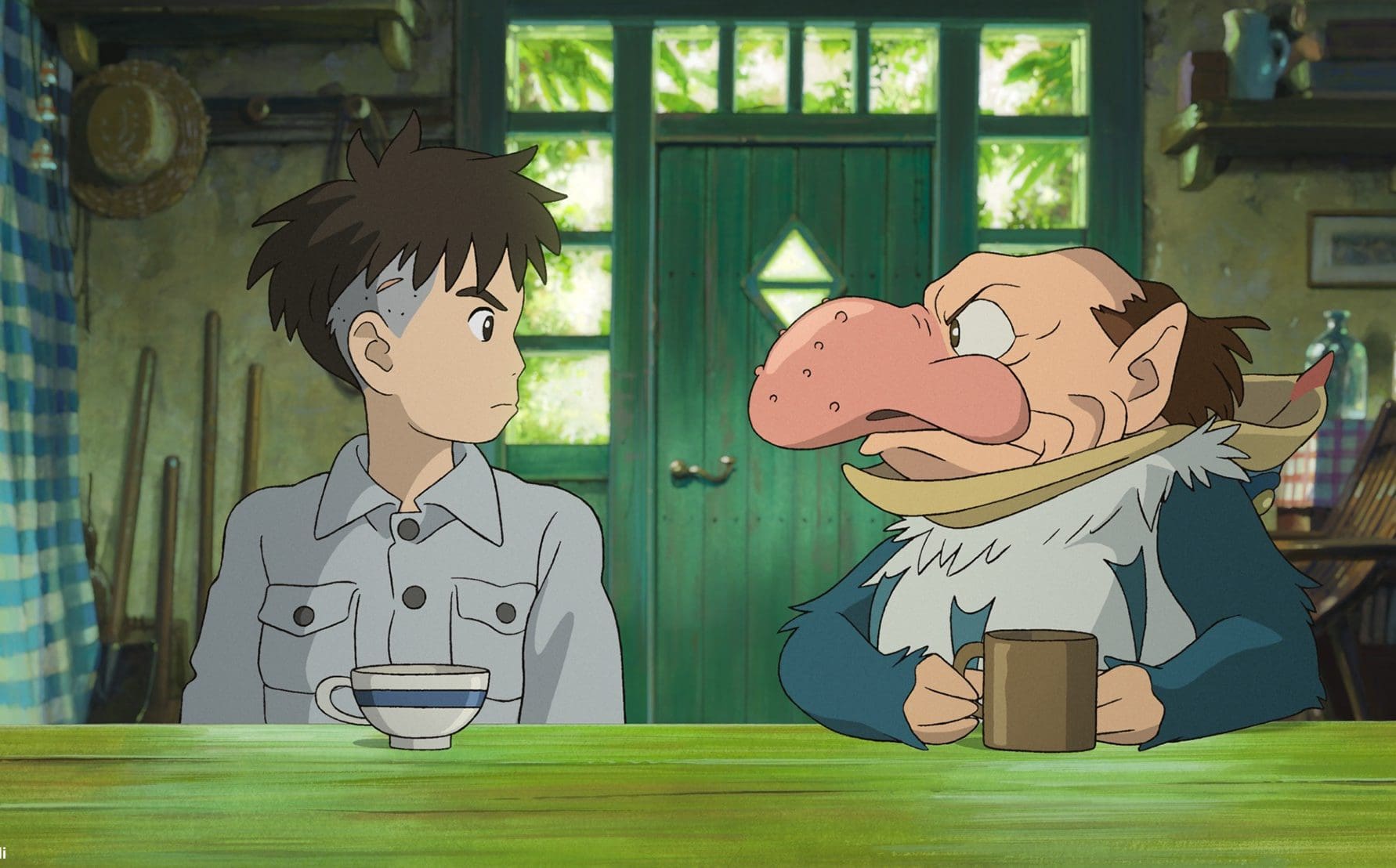

Those classic character and world designs return in a way that’s breathtaking and immediately feels aligned with Miyazaki’s most iconic films. There are clear visual nods and inspirations from Miyazaki’s past, further adding to The Boy and the Heron being a culmination of Miyazaki’s filmography. Not to mention, mixing this art style with a fantastic score from composer Joe Hisaishi is what makes The Boy and the Heron a strong technical showcase.

Despite relying on old tricks and styles, though, Miyazaki does implement more modern aesthetics and techniques. The movement seen in the film’s tense opening utilizes a unique blur effect that fits the scene’s fast-paced movement, palpable panic and chaos. The color palette is widened greatly and adds a vibrancy that’s seen in bright daylight as well as starry nights. There’s also a detailed realism in the backgrounds that adds a high visual quality to the simplest of scenes.

When it comes to sound design, The Boy and the Heron also utilizes that mix of old and new that makes the film feel like a classic yet refreshing entry in Studio Ghibli’s lineage as well as Miyazaki’s. The connections and inspirations of Miyazaki’s legacy are equally seen in the film’s story. The film, which is loosely inspired by Genzaburō Yoshino’s 1937 novel How Do You Live?, follows a young boy named Mahito (voiced by Soma Santoki) who is haunted by his mother being killed during WWII.

In the same way that Miyazaki’s former Ghibli co-founder and friend Isao Takahata did with Grave of the Fireflies, Miyazaki presents a unique perspective on WWII in the film’s opening moments, as Mahito’s Japanese village is torn apart by flames and bombs. It’s rare to see the Japanese civilian perspective during WWII—especially in American media—and it’s something that adds interesting layers to Mahito’s personal tragedy. The heart-wrenching opening of Mahito trying to fight flames and large crowds to find his mother is bursting with emotion and excellently sets the tone for the grief and anguish the film explores in Mahito’s arc.

After he’s forced to move with his father (Takuya Kimura) to live with his new wife Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), who is Mahito’s former aunt, Mahito struggles to get acclimated to his surroundings and ultimately lets his grief drive him. The early aspects of Mahito’s new life excellently instill this sense of grief and tragedy that latches right onto your heart. While there are bits of humor sprinkled in that embody Miyazaki’s writing style, it’s that lingering anguish that really sticks with you in the same way it does Mahito. It’s something that hits a realistic and mature tone that only Miyazaki could achieve and creates these relatable tethers that viewers can easily connect with.

However, Mahito’s life at Natsuko’s estate is greatly altered by the arrival and persistent taunting of a Grey Heron (Masaki Suda)—who’s more than they appear on the surface. This Grey Heron is simply the disguise for a small, man-like being who says that he can reunite Mahito with his mother. However, when Natsuko suddenly disappears into a crumbling castle that’s connected to Mahito’s family history, he’s forced to work with the Heron and others he meets along the way to rescue her and traverse an alternate reality. While The Boy and the Heron has a relatively grounded feel for its first half, it dives headfirst into Miyazaki’s fantasy antics but doesn’t necessarily stick the landing.

Miyazaki isn’t unfamiliar with suddenly bringing viewers out of reality and into a magical world just beyond our vision without warning. Frankly, it’s what makes films like Spirited Away and Princess Mononoke so special and the vibes of those films feel intertwined with The Boy and the Heron. However, there isn’t a lot of guidance going into the film’s fantasy world and it leads to an overwhelming and confusing second act. It suddenly becomes really hard to figure out what’s happening and there’s not enough direction within the story to keep viewers from feeling lost. Mahito being dropped into this fantasy world is similar to Chihiro’s experience in Spirited Away, but the moment happening in the middle of the film instead of the opening makes this sudden change very jarring.

Once the film enters its fantasy world, things also become disjointed in the story, and it can be tough to follow for quite a while. Eventually, the little details of the world and story forming around Mahito start to connect the dots. But the jarring shift creates so much extra work for viewers to process it and the choice breaks the well-built momentum and engagement of the first half. For general audiences, it could be where the film loses them and even the most dedicated Ghibli/Miyazaki fans might be a little taken aback by this sudden drop into fantasy.

Still, it’s hard not to appreciate the world that Miyazaki builds in this film and the more time viewers spend in it, the more intrigued they’ll become. There’s so much lore peppered throughout Mahito’s journey as well as the people he comes across and it features some amazing creature and character designs that evoke the best of Miyazaki’s fantasy vision. The Boy and the Heron is another instance of it being wonderful and mesmerizing to walk through a world built by Miyazaki—something that longtime fans will love. Plus, once the story details start to come together, Miyazaki delivers everything he’s great at: character-driven themes and interactions that are highly emotional and engaging.

With Mahito coming to grips with the loss of his mother and the hidden family history he discovers, his journey becomes a deeply personal and reflective look into grief and malice. While there are interactions that’ll have viewers laughing at the strangeness of this world and certain characters—namely a rebellious parakeet faction—there are also moments that’ll be incredibly heartwarming and touching.

Conversations between Mahito and other familial generations he encounters are moving and hold a deeper power that viewers can use to reflect on our world. It’s really compelling to watch Mahito’s personal growth as his perspective on Natsuko changes and his maturity and independence grow. There are supporting characters, like Himi (Aimyon), who are so loveable and play a strong role in Mahito’s arc that they easily rank among the most memorable of Miyazaki’s films. The emotions of Mahito’s final moments in the film are especially strong, though, for how they elevates the satisfying conclusions of his story and help wrap a neat bow around some of the connections built throughout the film. The Boy and the Heron has one of the most emotionally gratifying endings of Miyazaki’s films—mainly because of how simply satisfying it is and delivers messages that are worth sitting with.

The Boy and the Heron is a testament to Miyazaki’s vision for character arcs, compelling young protagonists, and relevant themes with a lot of staying power and relatability. Admittedly, the troubles of its second act shift will likely keep it from being seen as Miyazaki’s best or a completely satisfying conclusion (if it is the end, of course) for the filmmaker’s astounding legacy. But Miyazaki achieves something incredibly special with The Boy and the Heron that’s undeniable: he recaptures the beautiful art style that’s made him iconic and delivers a personal epic that will leave longtime fans holding back tears. It’s a genuine triumph that establishes Miyazaki as an all-time great and makes you feel like if he’s really done for good, that he ended things on accords—which should make every Ghibli fan’s heart swell and feel immensely satisfied.