Jane Austen’s comedy of manners Emma, about a young woman convinced she’s a great matchmaker yet unaware of her own feelings, has been on the big screen many times. In 1995, we got writer-director Amy Heckerling’s iconic reimagining, Clueless, only to get Douglas McGrath’s straightforward period adaptation starring Gwyneth Paltrow the very next year. Emma. the new adaptation of the novel directed by Autumn de Wilde and written by Eleanor Catton, feels like a synthesis of both. Though it’s set in the same regency era as the novel, the film has a more modern look and sensibility and while some of its affectations work, not every element ultimately succeeds.

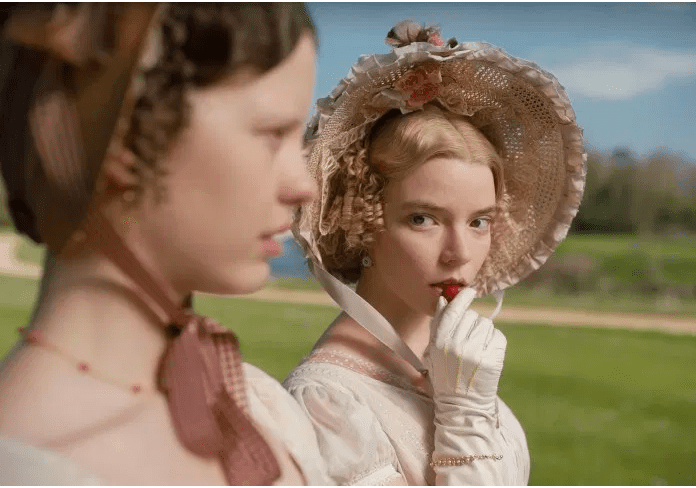

From the beginning, Emma.’s most distinctive element (and perhaps its greatest asset) is its production design and costuming. Though it’s all period appropriate, it’s all also clearly heightened. Everything from the clothes Emma (Anya Taylor-Joy) wears to the furniture in every room is pristine, brightly colored and clearly constructed. These characters may supposed to be real people in a real world, but they’re also in a comedy of errors and their candy-colored world cues us to laugh just as much as the dialogue and performances.

Speaking of the performances, they’re largely responsible for keeping this latest adaptation feeling light, fresh and funny. Miranda Hart is appropriately annoying yet endlessly fun as the cloying Miss Bates. Josh O’Connor is both dorky and slimy as Mr. Elton, the social-climbing clergyman who Emma tries to pair with Harriet (Mia Goth). Speaking of, Goth projects a ditzy, lovable sweetness that her previous roles haven’t afforded her and she may be the film’s biggest surprise. Taylor-Joy and Johnny Flynn as George Knightley, meanwhile, don’t get to go as broad and absurd as their costars since they’re tasked with delivering much of the film’s sharp-tongued wit, but they are still clearly having a lot of fun. Rather, where Taylor-Joy and Flynn most succeed is in selling their characters’ romance.

From their first banter-filled scene, there’s clear sexual tension between Emma and George and much of the film is about them first realizing it’s there and then acting on it. Unlike the film’s comedy or colors, that slow build is often expressed in subtle ways. Early on, it’s the way George stares admiringly at Emma holding her older sister’s baby or the way she playfully drags him into a verbal sparring match when they’re alone after. Later, it’s in the way George chastises Emma for a slip in manners or the jealousy in her eyes as she watches George and romantic rival Jane Fairfax (Amber Anderson) play a song together. Indeed, Taylor-Joy and Flynn are so skilled at gradually building their characters’ connection that it makes the scenes when that passion finally spills over that much more thrilling. So, it’s unfortunate, then, that so many of their brilliant choices are undercut by worse decisions on de Wilde and Catton’s parts.

Perhaps the most notable example comes right at the film’s end, just as it seems Emma and George are about to clear up the misunderstandings between them. Suddenly, in the middle of dramatic and heartfelt confessions, something happens to make both Emma and the situation feel ridiculous. It’s an unexpected if somewhat inconsequential turn, but one that deflates the passion from the scene. It’s not the first or even the last time something like that happens, but it’s certainly the most damaging and it’s only part of a series of bizarre choices that both wildly alter the tone and dampen the story’s effect. When it’s a smaller element like the too-jaunty and overdone score, it’s annoying if easy to dismiss, but the issues compound as the film goes on and eventually become too numerous to ignore.

In the end, all of Emma.‘s flaws feel somehow summed up by the extraneous punctuation at the title’s end. Like that period, the whole film is an affectation and all its elements add up to a distracting sense of self-conscious fussiness. While that tone allows the characters to feel like charming parts of a satire, it also undercuts the film’s emotional core. Neither the romance nor the personal hurts the characters experience mean anything because we’re not meant to really take them seriously anyway. It’s certainly a fun way to approach the material, but it’s also one that ultimately feels shallow.